Deep economic paralysis?

Amid the second wave of the pandemic, India enters into a situation that currently looks unimaginably distressed

The National Statistical Office's latest GDP data for the 2020-21 fiscal reiterates what was expected. But, the current financial year indicates the country's economy already slipping into a deep paralytic state. Lack of demand and consumption in rural areas that sustain two-thirds of the country's population is the reason behind this. This is also despite agriculture being the only sector that registered a positive growth with a gross value added of Rs 20.40 lakh crore in 2020-21. This year the monsoon is going to be above normal as well.

Between 2019-20 and 2020-21, India's GDP has reported a loss of Rs 10.56 lakh crore, or a -7.3 growth. But the data on consumption reiterates what was mostly expected: the economic slowdown led to en masse reduction in private consumption. Without this, no economy would even sprout.

Private consumption expenditure that accounts for 56 per cent of the country's GDP has reduced to Rs 75,60,985 crore (56 per cent of GDP) in 2020-21 from Rs 83,21,701 crore (57.1 per cent of GDP) in 2019-20.

That is 70 per cent of the total GDP loss. This also demonstrates the criticality of private consumption to economic growth. Before this, the country was already into the fourth year of consecutive economic decline. Private consumption, both in rural and urban areas, was not registering enough growth to fuel economic growth beyond the five per cent mark.

Per capita private consumption expenditure fell to Rs 55,783 per year in 2020-21 from Rs 62,056 in 2019-20. Consumption expenditure is a proxy for income and, in India, it is used to measure poverty level. Tentatively, using the above consumption expenditure, one can argue that the monthly per capita income in the country was Rs 4,649 per month in the first year of the pandemic. This was around 10 per cent less than the previous year's level of expenditure.

Indications

It indicates a decline in overall economic activities expected in the first year of the pandemic. But, the caveat: Even this expenditure was incurred when a significant number of people reported a loss in income or are in irregular jobs. It means most of them must have used up their savings. To sum up the accounting: People have either been left with no money currently or they are simply getting back to jobs, as the GDP data for the last quarter of last fiscal showed positive growth, even though minimal. This decline has impacted India in disproportionate ways.

From here, India enters into a situation that currently looks unimaginably distressed. The data came at a time when we assumed that the pandemic was almost over. The devastating second wave struck India in April, the beginning of the new fiscal.

The second wave is also breaching into rural areas, the resultant restrictions and lockdowns being widespread and longer. Given that half a billion people reside in India's rural areas, it could well be the world's first rural pandemic.

In the first wave, the rural areas were not that much impacted; rather it was a popular perception that COVID-19 was a disease of the urban areas. While we witnessed the overwhelmed health infrastructure crumbling in urban and megacities, how it would unfold in rural areas is a scary thought.

Will India repeat/worsen the economic situation over last year?

The impression is that it would be much worse than last year. The rural incursion of the infection makes India's recovery from the pandemic difficult and unpredictable.

The second wave, being rural by spread, turns out to be more devastating for the country's already poor. Experts foresee a vicious cycle for the country's over half a billion rural residents. Rural Indians — mostly an informal workforce and poor by any accepted definition — have lived with irregular jobs for over a year as the pandemic has been ravaging.

The second wave with more rural cases will further aggravate this economic crisis. The expenditure on health may also go up as cases rise, draining people's income or savings. Currently, all states in the country have imposed restrictions on movements and activities. The stringency of lockdown, unlike last year, varies from state to state and within a state, from district to district.

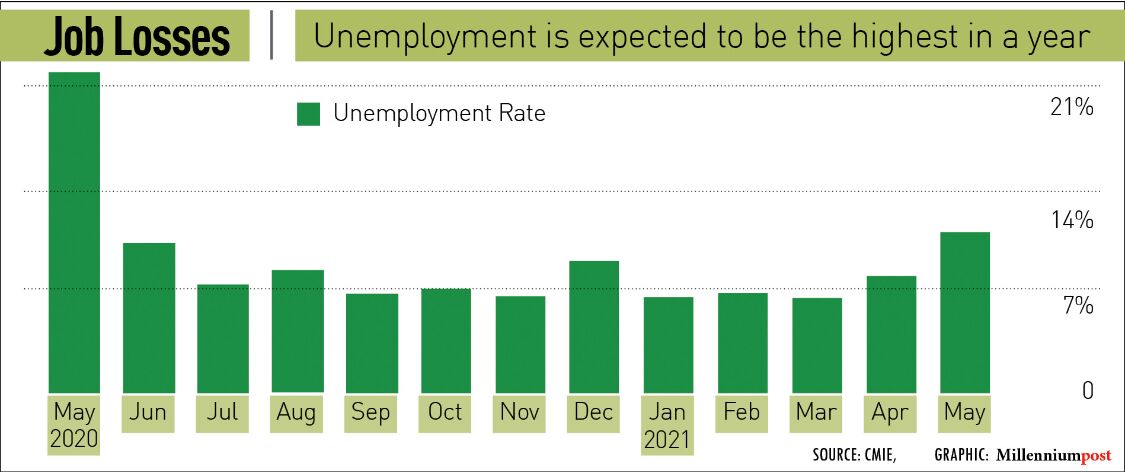

Similarly, lowering down restrictions will also depend on individual states. So, people without regular income for over a year are in a situation of extreme economic uncertainty. This perpetuates the cycle of poverty. All signs point towards this. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), job losses and unemployment are being reported from rural areas, unlike last year. CMIE's recent data indicate that the national unemployment rate is nearing the level of June 2020, the highest due to the national lockdowns.

"The pandemic has slowed down the labour participation rate to 39.9 per cent from an average of 42.7 per cent in 2019-20," said the Reserve Bank of India in its monthly bulletin for May. "By 2017-18, the unemployment rate was at a 45-year high. The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified this problem," says economist Santosh Mehrotra. The second wave, as various estimates show, has hit the unorganised sector the most. "Unlike the first wave, rural supply chains will be impacted because farmers and cultivators are also infected," Mehrotra adds.

Economic impacts of the lingering pandemic in rural areas would be devastating for the fact that mostly it is an informal and low-earning workforce. On the other hand, India's rural income comprises close to 46 per cent of the total income of the country.

Last year, the rural economy backed by robust agricultural growth and government spending on rural schemes somehow stayed put, though with cuts. But this year, it has also stagnated. The agriculture sector reported a three per cent increase in employment as millions returned to villages.

This year it can't absorb any more people. Also, the unfavourable term of trade results in less and less income despite bumper harvests. This will nullify the much-inflated benefit of a third consecutive normal monsoon. Less income means less consumption expenditure.

Similarly, 50 per cent of manufacturing and construction in India happen in rural areas which are significant employers as well. These suffer from lockdowns and also, due to overall lack of demands, activities have not picked up. Here as well, the rural areas will report a dip in income. Time to spare a thought! DTE

Views expressed are personal