Bloom of the billionaires

Even without an exception in a year of pandemic, the world’s leading billionaires added over one trillion dollars to their collective wealth

The rich will only get richer, irrespective of the poor getting richer or not. The same has been established since the financial crisis of 2008.

Usually, during this time of the year, one gets to know the world's newest billionaires, the already titled ones adding how much more to their corpus and the usual debate over inequality.

Most of the wealth index hit us during this time. The non-profit Oxfam brings out its wealth inequality report and the World Economic Forum takes place during this period.

But this year is unusual. The pandemic is still in grip of the world. Not a single country has reported growth per se. As the world economy is expected to contrast like never before, the per capita wealth was also expected to be down in comparison to 2019.

The world is sure about the addition of over 150 million extreme poor to the world by 2021, according to the World Bank estimate.

With this information, one would get curious about the impacts of the pandemic on the world's richest. Did they lose?

The Hurun Global Rich List is out on March 3, 2021. India has added 40 new billionaires in 2020. The list ranks Mukesh Ambani as the country's wealthiest with a net worth of USD 83 billion. He registered a 24 per cent growth in his wealth.

The world proudly welcomed eight billionaires a week as the pandemic rampaged across countries decimating their economies, the Hurun Rich List shows.

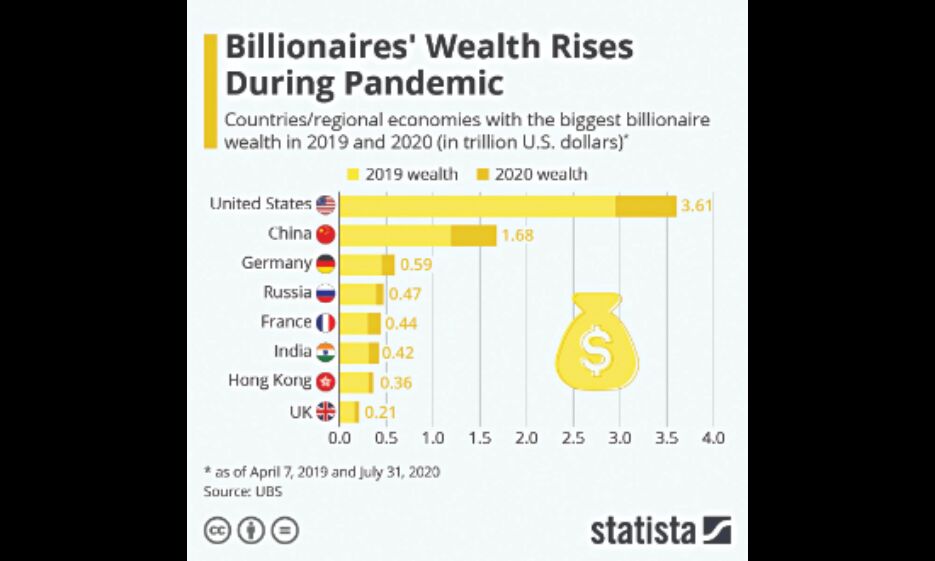

According to Statista.com, "The world's leading billionaires added over one trillion dollars to their collective wealth during the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic."

That this bloom of the billionaires continues uninterrupted, even without an exception in a year of pandemic, is the news. This makes that popular perception of "rich get richer, poor get poorer" into a stark piece of secular news.

If the past is the indicator of the present, inequality in wealth is now the essential by-product of economic growth. As we have been debating the death of capitalism and the free market model, the world after the 2008 global meltdown is a pointer to this fact.

By 2018, the 10th anniversary of the 2008 crisis, Oxfam reported that the number of billionaires had nearly doubled. "Meanwhile the wealth of the poorest half of humanity, 3.8 billion people, fell by 11 per cent," said one of its wealth distribution annual reports.

More to it, the "trickle" has not been ensured as only 4 per cent of taxes come from such wealth. Rather, in some countries (like Brazil and UK), "when tax paid on incomes and tax paid on consumption (value-added tax or VAT) are both considered, the richest 10 per cent are actually paying a lower rate of tax than the poorest 10 per cent".

The "super-rich" apparently hid USD 7.6 trillion from tax authorities. "There is no law of economics that says the richest should grow ever richer while people in poverty die for lack of medicine. It makes no sense to have so much wealth in so few hands, when those resources could be used to help all of humanity. Inequality is a political and a policy choice," said Oxfam.

Former IMF Deputy Managing Director David Lipton even blogged (though controversially) that voters across the developed and developing countries were losing "trust" in globalisation.

And he argued that this had the potential capacity to "tear down" the international order, read the globalisation model. An honest assessment but, as one delves a bit into his argument, he said so basically from the perspective of those who have already benefited from the recession since 2008.

He wrote: "This resentment will make it far harder for taxpayers' money to be used to shore up banks during the next crisis. If a future recession harms ordinary workers and small businessmen, states will come under pressure to financially support these people as they did for the banks in 2008. This could push up public sector debt to dangerously high levels."

One can realise how true he was. The pandemic just did that. But, as we experience now, countries are pumping in money to support the pandemic-struck citizens, even though not adequately. Public debt is surely increasing, and there is also enormous pressure on governments from the public to support it.

But it raises a question: if countries are supporting people just to tide over, and the economies are in shambles, how come a handful of individuals continue to remain unaffected by the downturn?

Earlier the Oxfam India said, "It would take an unskilled worker 10,000 years to make what Ambani made in an hour during the pandemic and 3 years to make what Ambani made in a second."

Another wealth ranking report called "Allianz Global Wealth Report 2020" in fact titled 2020 as the "Year of the Rich".

The annual report said:

"We didn't really have to wait for the pandemic to wipe out the progress made in making the world more equal in terms of wealth distribution. 2019 widened the wealth gap between rich and poor countries again, increasing the difference in net financial assets per capita to 22 times from 19 times in 2016."

This is still well below the gap of 87 times that we had in 2000 but the trend reversal is disturbing indeed, the Allianz report said.

There is inequality in wealth. But in case of a disaster that struck all, there were surmises that the level of inequality might come down. But in reality, it has further widened.

Allianz economist Patricia Pelayo Romero was quoted saying, "It is quite worrying that the gap between rich and poor countries started to widen again even before COVID-19 hit the world."

"Because the pandemic will very likely increase inequality further, being a setback not only to globalisation but also disrupting education and health services, particularly in low-income countries."

The writer is Managing Editor, DownToEarth. Views expressed are personal