Trail of a ‘green’ crusader

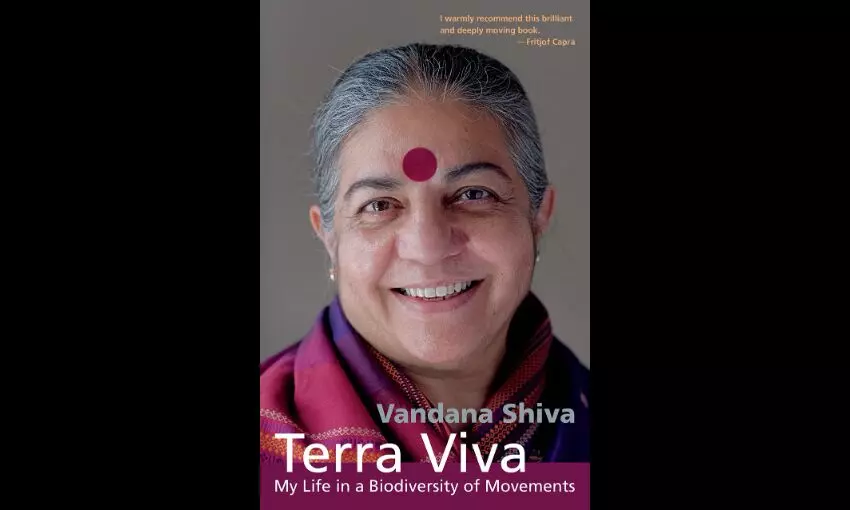

An intricate collection of nine essays, Terra Viva is an autobiographical narrative by Vandana Shiva that takes readers on her four-decade long ecofeminist journey dotted by numerous campaigns advocating for diversity, indigenous knowledge, localisation, and real democracy

The internet search attributes two captions of ‘Terra Viva’ to Vandana Shiva — the first being the ‘Manifesto’ prepared under her leadership to mark 2015 as the UN year of the Soil, and the second being her autobiographical narrative (Terra Viva) published to coincide with her 70th birthday last year. This is an interwoven collection of nine essays which take us on her eco-feminist journey – from a life in the lap of nature, to activism in the Chipko, the movement against patenting of seeds, the role of women in ensuing and securing biodiversity, the unequal treaties and protocols of WTO and its predecessor organisation the GATT, the campaign against privatisation of water of Mother Ganga (as also other rivers), a discourse on biodiversity and biotechnology, the politics and practise of climate change, and last, but not the least the intertwined fates of biome and viome. But, first a few words about our muse Vandana Shiva who has been described in many ways: the “Gandhi of Grain,” “a rock star” in the battle against GMOs, and “the most powerful voice” for people of the developing world. For over four decades she has vociferously advocated for diversity, indigenous knowledge, localisation, and real democracy; she has been at the forefront of seed saving, food sovereignty, and connecting the dots between the destruction of nature, the polarisation of societies, and indiscriminate corporate greed.

Let me first talk about the Manifesto which has the following Sanskrit verse from circa 1500 BCE as the Preface:

Upon this handful of soil

our survival

depends. Husband it and it will grow our

food, our fuel, and our shelter and surround

us with beauty.

Abuse it and the soil will collapse and die,

taking humanity with it

The context was the UN General Assembly’s declaration of 2015 as the International Year of Soils (IYS) with the aim to “create full awareness of civil society and decision makers about the fundamental roles of soils for human’s life. The IYS also sought to achieve full recognition of the prominent contributions of soils to food security, climate change adaptation and mitigation, essential ecosystem services, poverty alleviation and sustainable development”.

The Manifesto was a transformative document which showed how critical issues and crises were interconnected and could not be addressed in silos: soils, land and land grab, farming, climate change, unemployment, growing economic inequality, and growing violence and wars went together. It pointed to the need for making a shift from the current linear, extractive way of thinking to a circular approach based on reciprocal giving and taking, a society based on justice, dignity, sustainability, peace and a true democracy. A reading of her Manifesto helps in understanding the polemic of her argument. In her defence, it must be said that she is not an academician talking about the pros and cons of different views: she is an activist and a campaigner, one who marshals all the facts at her command to buttress her argument. She is an advocate for the ‘organic way of life, for preservation of seeds, for slow-food movement, for the control of resources by communities rather than corporates, and so her writings reflect this.

This is the context in which the book has to be read – for while it is true that the book is a ‘listicle of her achievements’, the organic movement needs this assertion. As a Joint Secretary in the Union Agriculture Ministry and as the head of Agriculture Department in the states of West Bengal and Uttarakhand, I am aware of the ingenious ways in which the fertiliser lobby and the ‘crop care’ (pesticide and insecticide) industry couch their arguments. The strength of the organic has never been contested directly – what is said is that “what is sold as organic is not certified”, that “organic cannot meet the requirements of large urban centres”, and so on and so forth. The unfortunate part is that the way our knowledge systems operate, the value ascribed to the written word or a documented research paper is a multiple of the knowledge held by women, forest dwellers and all those who are part of the oral episteme. Thus, with respect to biodiversity, she writes “the term knowledge society, as a description of computer-based societies is so inaccurate and misleading, implying that the non-industrialised, non-computerised societies are without knowledge. In the case of biodiversity, forest species and plant species, this is clearly not true: women and the indigenous communities, the excluded of the industrial world, are the real custodians of biodiversity related knowledge”.

I will not discuss the chapters on Chipko, seed sovereignty and her stand on WTO, for these are quite well known, but the chapters like the Great Water Capture in which she shows how across the world, corporates are drawing water for commercial gains. Companies like Coca Cola have drawn so much water that the hinterlands have been left dry, and campaigns like Washing Hands camouflage outreach for soaps as a campaign for pubic hygiene.

In her essay on No Patents On life, she makes a strong case for the biodiversity of the mind — the ability to see all of life’s processes in all their complexity and multiplicity. We also understand that while the European Union is quite clear about not allowing GMO in their territory, the MNCs are quite happy to push these in countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America where the regulatory regime is weak, or easily available for capture. Thus, introducing BT brinjal in Bangladesh is a good strategy – if it works there, it may as well work in India and all of South Asia. But the larger issue is: why is so much money being spent by the CGIAR system on brinjals, and not on dryland agriculture, berries, nuts, millets and all such crops which can be grown by communities without external inputs?

Some reviewers have pointed out that while “she has built, nurtured and led effective global coalitions that have stood the test of time, in her telling, these seem to come into being fully formed and perfectly aligned. There is little to help us understand what the particular challenges, big or small, were and continue to be, in keeping groups of people across geographies united by one cause: the health of the planet”. While the cause may seem lofty enough to hold people together, individual or vested interests often break partnerships. That Shiva and her partners have stayed together through thick and thin is indicated, but her role and how those challenges shaped her, helped in her personal growth, do not come through.

Well, there is some merit in this observation, and therefore this reviewer hopes that she will address issues relating to the ‘coalition dharma’ as well – for the ability to foster and nurture intercontinental networks of communities, academics, activists, NGOs, donors and ethical entrepreneurs is a lesson by itself.

Vive La Terra Viva, Vive La Vandana!

The writer, a former Director of LBS National Academy of Administration, is currently a historian, policy analyst and columnist, and serves as the Festival Director of Valley of Words — a festival of arts and literature.