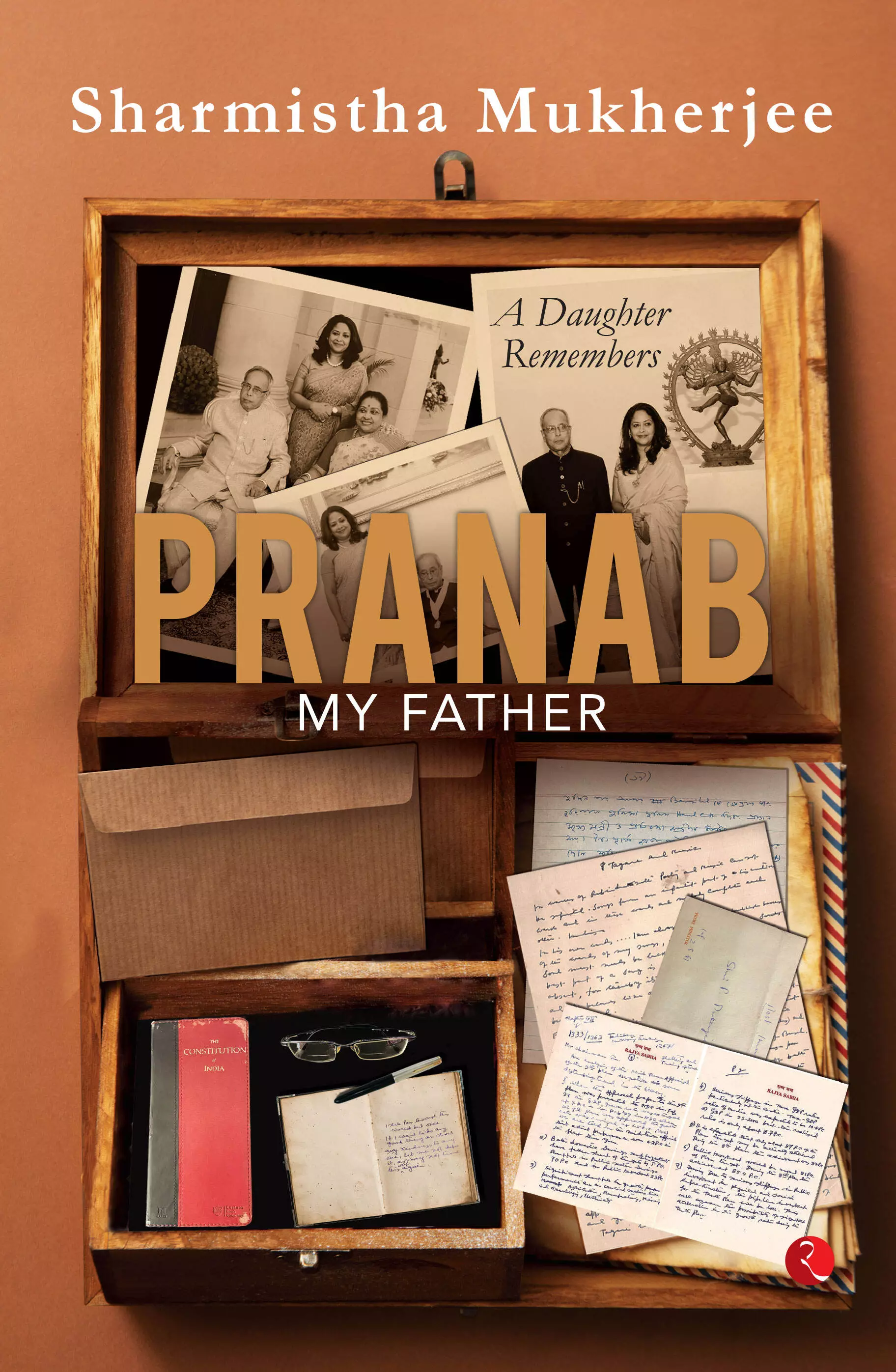

Portrait of a father

Based on extensive research, personal anecdotes and Pranab Mukherjee’s diary entries, Sharmistha Mukherjee, in the evocatively written book ‘Pranab, My Father’, offers a warm glimpse into the illustrious life of the 13th President of India. Excerpts:

Pranab was a product of Parliament. For him, it was an institution whose paramount importance in public life and deciding the fate of the nation could never be emphasized enough. He always said that his incredible journey from an obscure village in rural Bengal to the highest constitutional office in the Republic of India was possible only due to the democratic system and ethos enshrined in the institution of Parliament. He first came to the notice of the then PM Indira Gandhi through his speech in Parliament. It was there, over the years, that he developed relations with leaders of other political parties. Through debates held in its hallowed chambers, he learnt the view points from the other side of the spectrum. He learnt to argue, counter-argue, concede if necessary or held on to his point of view and convinced others when needed. He learnt to listen and disagree amicably, and incorporated the valid points made by Opposition leaders in the larger interest of the nation and its people.

Parliament taught him to respect views contrary to his own. It gave him a vast and diverse resource base of brilliant minds. He would regularly take inputs from debates to further strengthen a government bill or international negotiation. He told me how once during a debate in Parliament regarding an international treaty, he incorporated some of the points raised by Dr Subramanian Swamy (a member of the Opposition) into the agreement.

He often liked to say that Parliament is not a debating society where you score points to shine individually. It is a political institution that, through its members, represents each and every corner of this vast nation and its massive population. Decisions taken here affect more than a billion people.

While in government, he would meet Opposition leaders both formally and informally before the presentation of major bills. He would then thrash the bill out with them. Even before the bill was tabled, its key points would be discussed and efforts would be made to iron out contentious issues. This is something he learnt from Indira Gandhi. It was not that he was always able to ensure the passage of government bills. However, the idea behind this exercise was to involve the Opposition leaders in the democratic process of enacting legislations.

He did this not just when he was in the Treasury Bench. Even as an Opposition leader, he would urge his party to extend their cooperation to the government whenever it was necessary in the greater interest of the nation. In 2002, the Patents (Amendment) Bill was tabled by the Vajpayee government. It was crucial to get the Bill passed, as India was in danger of expulsion from the World Trade Organization (WTO) due to non-compliance of obligations voluntarily made by India. Hence, it was required to get the necessary amendments done in the Patents Act of 1970. Incidentally, the same amendment bill was submitted by Pranab as minister for commerce in 1994 during the P.V. Narasimha Rao government. They could not get it passed then due to stiff resistance from the Opposition parties. However, this time it had a sense of urgency, as complaints were pouring in and India’s standing in the international community was in danger of being seriously compromised. In 2002, while the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government could get the Bill passed in the Lok Sabha due to its majority, in the Rajya Sabha it needed Congress support. Prime Minister Vajpayee spoke to Pranab and Dr Manmohan Singh, seeking their support. Pranab spoke to Sonia Gandhi and explained to her the gravity of the situation, and the consequences if Parliament failed to make the necessary amendments. She agreed and the Bill was passed. In the interest of the nation, it was necessary to rise above petty party politics.

Pranab often said that in a vast and diverse country like India, politics and governance is nothing but management of conflicts and trying to create a balance between varied and contradictory interests. According to him, Parliament was the best institution to learn that.

Once during UPA-II, I was watching a debate on Rajya Sabha Television in which Arun Jaitley, the then Leader of Opposition (LoP) in Rajya Sabha was speaking. He complained about how ministers from the ruling party did not take Opposition leaders into confidence for decision-making. Pranab was about to intervene. But before he could, Jaitley corrected himself by saying that Pranab was the only one who talked to the Opposition leaders. It is ironic that just a few years down the line, when Jaitley’s own party came to power and formed the government, they completely overlooked the necessity of democratic involvement of the Opposition. They indulged in bulldozing important legislations through the force of brute majority without even affording adequate time for debates.

At a personal level, Pranab was very fond of Jaitley. He was extremely upset when he passed away in August 2019.

During the course of my short stint as a political activist, I came across many senior leaders across the political spectrum, including in the BJP, who told me that Pranab was like a mentor to them in Parliament. He would not only teach them about parliamentary rules and regulations, but would also tell them which points to raise; regale them with anecdotes; boost their confidence after a good speech; help them analyse their speeches; and give suggestions on ways to improve their speech, even if that person was sitting on the other side of the fence. In his diaries, over the years, Pranab meticulously evaluated his own performance while delivering a speech. After a good speech, he would note that leaders cutting across party lines would come and congratulate him.

This practice of senior leaders encouraging bright young MPs exists even now. Sushmita Dev, who was a first-term MP from the Congress in the Lok Sabha in 2014, told me that many a time, after noisy outbreaks in the House had subsided, senior leaders from across the divide would congratulate her on delivering a good speech. She narrated an interesting anecdote to me. She had to speak on Payment and Settlement Systems (Amendment) Bill presented by the then Finance Minister Arun Jaitley. As there was little time for preparation before the speech, and the Bill was too technical, she met Jaitley ‘informally’ in Parliament for some clarifications. Jaitley not only explained the Bill to her but even suggested a few points that she could raise in her speech!

LESSONS FROM THE SOUL OF DEMOCRACY

Pranab learnt by himself and was also assisted throughout the initial years of his parliamentary career by his seniors, from different sides of the political spectrum. By his own admission, two stalwart parliamentarians and judicial luminaries—M.C. Chagla and M.C. Setalvad—took a liking to this shy, unsophisticated first-timer and decided to take him under their wings. Bhupesh Gupta, a member of the Communist Party of India (CPI), who was a legend in parliamentary procedures, would create tricky problems for Pranab when he became the leader of the House in Rajya Sabha, but would also offer suggestions to solve the impasse. I discovered an interesting handwritten note without any date on the Rajya Sabha notepad in Pranab’s papers after his death. The yellow tinge and the fragile condition of the paper indicated that it must be quite old. It read, ‘Pranab, please say no more than I have already expressed my views this morning.’ It was signed as ‘Piloo’. I presume it must have been a note from Piloo Mody, a veteran parliamentarian and a member of Opposition. Yet, he came to the rescue of his young friend when Pranab was probably being grilled on the floor of the House as a minister.

(Excerpted with permission from Sharmistha Mukherjee’s ‘Pranab, My Father’; published by Rupa Publications)