Pen and penury

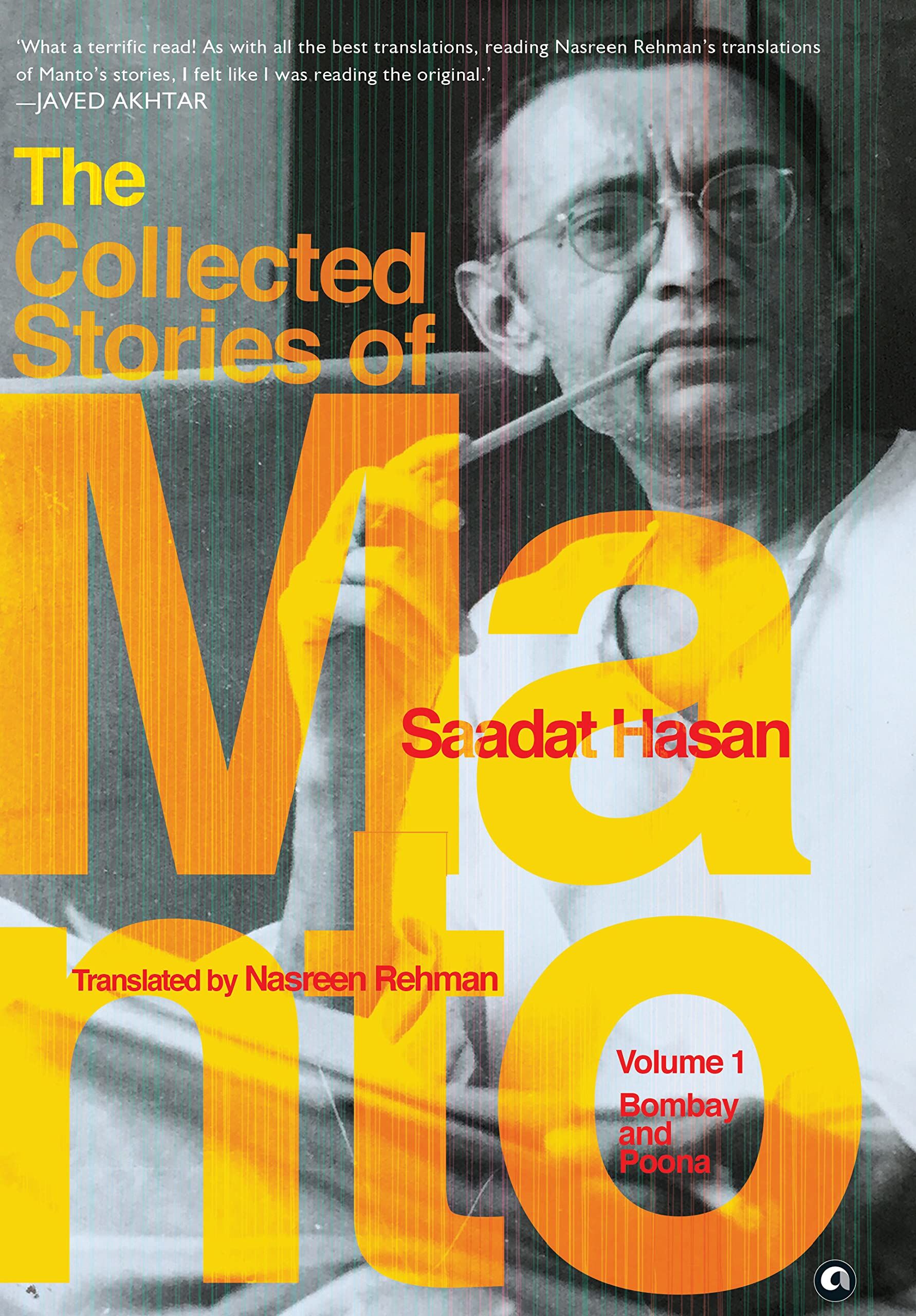

In this first part of the three-volume book — The Collected Short Stories of Manto — Nasreen Rehman deftly executes the onerous task of translating 54 short stories of the cult writer whose honest works not only best depict his era but also breathe freshly in today’s literary landscape. Excerpts:

Somewhere, I have written about three significant accidents in my life. The first was my birth, of which I know nothing; the second was my marriage; and the third was my becoming a short-story writer. Since the third is ongoing, it would be premature to say anything about it. However, to satisfy the curiosity of people who wish to peep into my life, I shall recount the tale of my marriage, not exactly as it happened because discretion demands that I skirt around specific issues.

First, let me present the background to this accident. I do not recall the year, but twelve or thirteen years ago, I was diagnosed with consumption and thrown out of Aligarh University. I took some money from my sister and went to convalesce in Batote, a village between Jammu and Kashmir, where I spent three months. When I returned home to Amritsar, I learnt that my sister's son had died. She had been married off to someone who lived in Bombay. She spent a few days in Amritsar with Bibijan, our mother, and returned to her marital home.

I think it is worth adding that I had lost the protection of a father at a young age. After my sister's marriage, my good-hearted and guileless mother handed over all our worldly belongings to my brother-in-law, and this left Bibijan and me at the mercy of others. My two older brothers gave us forty rupees a month. I returned to Amritsar with a troubled heart and mind and wanted to perish or commit suicide. If I were stronger willed, undoubtedly, I would have killed myself. Such was my state of mind when Mr Nazir, the owner of the weekly 'Mussavir', wrote to me from Bombay and invited me to take over the editorship of his journal.

I packed my bag and baggage and set off for Bombay. It did not cross my mind that I was leaving Bibijan all by herself in Amritsar. Mr Nazir hired me as his servant at forty rupees a month. I slept in his office, and for this, he deducted two rupees from my monthly salary. Still, Mr Nazir got me fixed up as a munshi, a dialogue writer, at the Imperial Film Company, at forty rupees a month, and cut my pay by half. So he paid me twenty rupees a month, from which he deducted two rupees for my use of his office as a residence.

When I arrived in Bombay, the Imperial Film Company had scaled the heights of fame and was now in decline. Its intrepid owner, Seth Ardeshir Irani, was doing his utmost to stabilize his company's fortunes. Obviously, employees did not get their salaries on time. Seth Ardeshir had earned fame and fortune as the producer of 'Alam Ara', the first Indian talkie. He desired similar recognition as the producer of the first technicolour film and committed a fatal error: he imported new colour processing equipment

from abroad. When the weight of colour landed on Imperial's shoulders, its already shaky finances began to wobble further. Yet, somehow work continued, and we were paid something by way of an advance, with the balance credited to our accounts.

Seth Ardeshir handed over the direction of the technicolour film to Mr Moti B. Gidwani, an educated man who happened to like me, and asked me to write the story, which I wrote and he liked, but there was an obstacle. How was he going to convince Seth Ardeshir that the screenwriter of the first technicolour Indian film was an ordinary, unknown munshi? Gidwani gave the matter much thought and concluded that to secure a sound financial deal, we needed the name of a well-known personality. There was no such person in my immediate circle. When I cast my mind about, my thoughts turned far away to Professor Ziauddin, who was teaching Persian at Santiniketan, Tagore's university, and was well-disposed towards me. I wrote to him, and he became complicit in our fraud. His name appeared in the credits for the screenplay. 'Kisan Kanya' flopped at the box office, and the company's finances deteriorated further.

In the meantime, Mr Nazir pulled some strings, and I got a job in Film City for hundred rupees a month. Kardar Sahib had arrived in Bombay from Calcutta, and Film City finalized a deal with him; he invited stories and liked one of mine. Work started on the film, but Fate had other things in store. Seth Ardeshir Irani discovered I was working at Film City. Although he no longer retained his former stature, he continued to exercise considerable influence and power over all film-makers of his generation. He gave such an earful to the owners of Film City that they sent me and my story packing back to Imperial Film Company. Now, however, instead of forty, I was earning eighty rupees. Although the company promised me an additional sum for my story, I never received that payment. Hafizji, of Rattan Bai fame, was chosen to direct this movie.

After starting work at Film City, I gave up my accommodation in the 'Mussavir' office and rented a kholi at nine rupees a month in a squalid chawl, where bedbugs rained down from the ceiling. It was at this time that Bibijan moved to Bombay to live with her daughter. I had a fraught relationship with my brother-in-law, may God bless him—he was a bad character. Since I did not refrain from denouncing him, he forbade my entry into his house and my sister from meeting me.

Bibijan dropped by to visit me. When she saw my fleapit, she wept and lamented how the wheel of time had reduced to penury her son raised in comfort. My mother could not bear the idea that I worked through the night by the light of a kerosene lamp and ate every meal in a hotel. All the time Bibijan spent with me in my kholi, she continued to weep, and this was both mentally and spiritually punishing for me. I live in the present, and think it a bit pointless to dwell on the past and fret about the future. What has happened has happened and what will be will be. When done with her weeping, Bibijan turned to me and asked in all seriousness, 'Saadat, why don't you earn more?' I replied, 'Bibijan, what will I do by earning more? Whatever I earn is enough for me.'

(Excerpted with permission from Nasreen Rehman's The Collected Short Stories of Manto; published by Aleph Book Company)