Magnificent mosaics

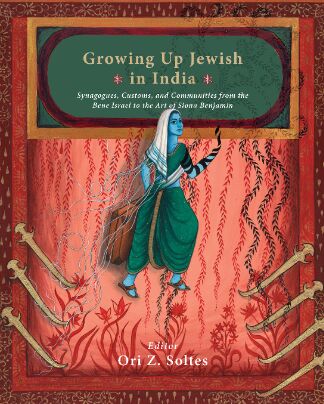

Ori Z Soltes’ Growing Up Jewish in India is a unique verbal and visual portrait of the synthesis of Jewish culture and tradition in the country — tracing their early arrival and seamless dispersal across India and beyond; Excerpts:

My parents (and I) lived in what everyone called the Bollywood suburb of Bombay (now known as Mumbai), a bustling city on the west coast of India. My mother, a Bene Israel Jew from Pune (a small city near Bombay) ran a private Montessori school for 20 years and drew on mostly the children of glitzy movie stars (Bombay being the Mecca of the movie-making industry in South Asia). So quite often I had to sit through three-hour-long Bollywood movies, which—to sum up quickly—were mostly Indian versions of Rambo with the spice of some song and dance thrown in. One minute the hero was beating up the villain (whose side kick almost always was this British actor whom he called Anthony and who incidentally never said a word but just carried out the treacherous orders of the villain) and the other minute the hero would be prancing around in the middle of corn fields belting out a song with a doe-eyed damsel dressed in chiffons.

My parents were staunchly Jewish and proud of it (especially since India was one of the only countries where there was no antiSemitism). So they carried out rituals and observed Jewish festivals with great fervor, and before what seemed like the exodus of the Jews from India to Israel mostly in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, I remember preparations for the Eliyahu HaNavi prayer (invoking the prophet either to help or in thanksgiving)—recited at circumcision and baby girl-naming ceremonies, before engagements and weddings, and during certain holidays—and the Malida service, the Sabbath and large pots of Jewish halwa (sweets) made out of coconut milk for the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur festivals.

Like every group, Indian Jews have unique stories, rituals and authentic melodies in their prayers. Centuries of living in India made them blend together different influences from their surroundings. When someone asks me—especially here in America—why we Indian Jews eat Indian food or why we have a henna ceremony for our weddings, or why Indian Jews speak Marathi and not Yiddish, I remind them that Jews in every part of the world have been influenced by their own surroundings. So why can't Indian Jews make spicy curries or Indian Jewish brides have henna decoration on their hands?!

The Eliyahu HaNavi prayer is unique to the Indian Jews, particularly to the Bene Israel Jews from the Konkan coast of West India. I recall going with my parents, grandmother and all my family to the small towns of Alibag, Revdanda, and Khandala (south of Bombay city in the Konkan region) where my father's family owned some farm land. There the Elijah Rock is believed, in the Bene Israel tradition, to be the location where Elijah the Prophet (Eliyahu HaNavi) left to go up to heaven. I was taught to believe that the marks on this rock were the marks of the prophet's chariot wheels just before he ascended. It is still considered sacred by all Bene Israel Jews and people come from far and wide to worship at this place.

My family would also congregate and often conduct prayers to the prophet and have a Malida ceremony. Malida particularly linked to the traditions of my Bene Israel community and was special to me and to all of my family. I still recall the fragrant smell of the Malida platter, made from flattened sweetened rice and dried fruits. As the prayers advanced there were special rituals, like the smelling of cloves that were part of the ceremony. Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, Syzygium aromaticum. They are warm and spicy to smell and I remember their fragrance so very distinctly. Instead of the spice box for Havdalah (the ceremony to mark the end of the Sabbath), with a numerous blend of spices that I have sometimes experienced in Jewish homes in the US, Indian Jews just used cloves—in fact, one single large clove was handed to each participant in the prayer and after the prayer was recited. I recall and I still associate the smell of cloves with my childhood. Coconuts and dates were also part of the Malida platter as they are fruits of the desert, making us remember the land of Israel. Other fruits also decorated the platter and after the prayers the womenfolk in my family would serve us this delicious Malida.

I also recall an old synagogue in this area and very near my grandmother's family farm. There were several synagogues in the Konkan area south of Bombay, but the Revdanda Synagogue was the one I recall the most. Always brightly painted, it stood out in the Indian landscape with its bright pink gates with menorah symbols on them. Inside, the synagogue was colorful, too, with velvet curtains that covered the Torah Ark. Wooden benches arranged in a semi-circle surrounded the central bimah (tevah) where the hazan reciting the prayers would be facing the Torah Ark. Later, when I came to live in America, I remember finding it different where the congregation in Ashkenazi synagogues faced the Torah ark but the person at the bimah had his back to the Ark. Indian synagogues are all like theaters in the round and people sat around the centrally located bimah.

Other little memories are so unforgettable, like the large Bene Israeli style mezuzah at the door of our home; my father kissing it when he left to go to work and when he entered our home upon his return. My mother lighting the shabbat lamp every Friday; she made her shabbat lamp in a glass bowl with oil and water, the oil floating on top of the bowl and the wick staying lit almost all night long! My mother taught me some prayers, particularly the shema, which I recited every night before falling asleep. Later on, this was important to share with my daughter and she had her Indian-Jewish Bat Mitzvah inspired by her grandmother's stories and her visits to Jewish India. Yet another amazing full circle achieved! I designed a tree of life for my daughter's Bat Mitzvah tallit (prayer shawl), my mother got it embroidered in India and she then hand sewed 613 red beads on it—their number symbolizing the 613 mitzvot (commandments, but the term comes to refer to good deeds, as well) in the Torah and their color symbolizing pomegranate seeds with their connotation of fertility and thus of good fortune—as a special blessing for her granddaughter. These little memories are the inspiration for, and the basis of, my version of a prayer that I offer through my art-making.

My schooling…well, I started off in a private Catholic convent school run by British, Swedish, and Indian nuns and I ended up doing my high school in a Zoroastrian (Parsi) school. These schools somewhat remind me now of parts of the Harry Potter movie…no, we did not have changing stairs and flying brooms, but we did have thick stone walls and nuns in white who seemed to glide down the stairs in a very Harry Potterish way. So, to give you a snapshot, Sister John of the Cross and Sister Mary Magdeline would conduct the daily Hail Mary prayers and then we stood in pinafored rows in our separate houses to be taken to gym or to our respective classes. I belonged to the Green House, otherwise known at the House of Scott—Sir Walter Scott that is—other houses were: Red, which was Shakespeare; Blue was Tennyson, and Yellow, Dickens. The high school was just as formidable—the same thick stone walls (which, by the way did little to stop the interaction with the boys' school next door, which was run by the priests), and the large open fields that looked onto the Arabian Sea. So here we were, girls with names as diverse as Radhika Verma, Zehra Mahmood, Kawaljeet Singh, Yevonne Aptekar and Miriam Abraham (the other two Jewish girls in the class) and others like my friends Lorraine DeSouza, Annabel Fernandez, Mohini Char and Nuzhath Iraqi.

(Excerpted with permission from Ori Z Soltes' Growing Up Jewish in India; published by: Niyogi Books)