A scholarly inheritance

It was the enlightening ideas of Swami Vivekananda and strivings of Jamsetji Tata that laid the bedrock for the marvel of the Indian Institute of Sciences that attained completion through Sister Nivedita’s efforts

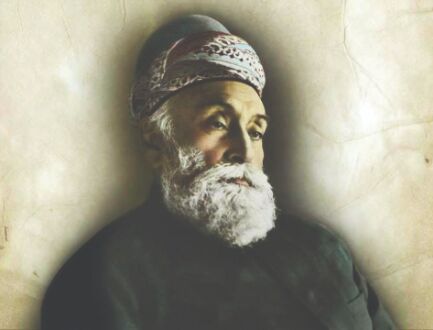

On November 23, 1898, Jamsetji N Tata — a renowned businessman — wrote a letter to Swami Vivekananda, requesting him to write a pamphlet to raise awareness around setting up of an educational institution where natural science, basic science, ethics, metaphysics and psychology would be taught by following traditional and modern methods. Tata even agreed to bear the cost of printing the pamphlet.

Tata's letter dated November 23, 1898, read:

"Dear Swami Vivekananda, I trust, you remember me as a fellow traveller on your voyage from Japan to Chicago. I very much recall at this moment your views on the growth of the ascetic spirit in India, and the duty, not of destroying, but of diverting it into useful channels.

I recall these ideas in connection with my scheme of Research Institute of Science for India, of which you have doubtless heard or read. It seems to me that no better use can be made of the ascetic spirit than the establishment of monasteries or residential halls for men dominated by this spirit, where they should live with ordinary decency and devote their lives to the cultivation of sciences – natural and humanistic.

I am of opinion that if such a crusade in favour of an asceticism of this kind were undertaken by a competent leader, it would greatly help asceticism, science, and the good name of our common country; and I know not who would make a more fitting general of such a campaign than Vivekananda.

Do you think you would care to apply yourself to the mission of galvanizing into life our ancient traditions in this respect? Perhaps, you would better begin with a fiery pamphlet rousing our people in this matter. I would cheerfully defray all the expenses of publication."

Jamsetji was a frequent visitor to Japan and used to import matchsticks which he sold in India. During one of his trips to the United States via Japan, he met a robust-looking young unknown monk who was on his way to the US to attend the Columbian Exposition, a fair which was organized to celebrate 400 years of the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus.

Jamsetji (1839-1904) was 54 years old when he met the unknown young monk Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902) who was just 30 years old. Vivekananda was 24 years junior to Tata. However, Tata felt tremendously attracted towards Swamiji because of his appearance and clarity of thought. Every morning, till late in the afternoon, they sat on the deck and discussed various issues. More often, they discussed setting up educational institutions, particularly research organizations, where Indian students would get an opportunity to work freely. Tata was going to the United States to talk to the steel magnets so that he could import steel in India. Swamiji requested that a person like his stature should set up a research organization where Indian students could know more about steel and do research.

The ship, Empress of India, reached Vancouver on July 25, 1893, at night. Tata left for his destination and Swamiji went to Chicago to attend the religious conference. On September 11, 1893, Swamiji delivered his historic speech and became famous. It is interesting to note that during Vivekananda's tour to the United States and Europe between 1893 and 1897, Tata did not write any letter to Swamiji, or sent any telegram to congratulate him for his success at the Chicago World Parliament of Religions, but he remembered his exchanges with the Swami on the voyage.

And the monk's dialogues were so logical that Tata decided to keep Rs 30 lakhs to set up a research university. So, when Swami came back from the West in 1897, he wrote a very humble letter expressing his desire.

On December 31, 1898, Lord Curzon reached Bombay to become the Viceroy. He came to Calcutta on January 6, 1899, to take up his new assignment. Tata sent his sister and one of his friends Mr Padshah to see Lord Curzon, and they told him about Jamsetji's dream of setting up such an institution. Curzon, at once, rejected the proposal and told them rather rudely that such an institution would not help Indian students in any way and, moreover, there was no one in India to head such an institution.

Shocked at Curzon's arrogance and blanket refusal for his project, Jamsetji sent his sister and Badjorji Padshah to Swamiji at Belur Math in February 1899 to discuss the matter with him and seek his opinion. They held a closed-door discussion for over an hour, and after the meeting was over, neither Swamiji nor the messengers of Tata did say anything in public. Prabuddha Bharat wrote two editorials on Tata's project. In its April 1899 issue, Prabuddha Bharat gave Swamiji's view on the project, along with his observation that Indians should install a golden statue of Tata at the Bombay Port for his noble cause to spread education in India.

Though Swamiji could not reply to Tata's letter because of his busy schedule after he returned from the West on February 19, 1897, he set up the Ramakrishna Mission on May 1, 1897. Ramakrishna Mission played an important role in serving the needy at the time of the Plague in 1898. Yet, Tata continued to maintain a very cordial relationship with Swamiji. Once Tata told Josephine Macleod that people in Japan had so much respect for Swamiji that whenever they saw him on the road, they moved aside and allowed him to walk on the street.

Swamiji left for the West in June 1899 along with Sister Nivedita and Swami Turiyananda. Swamiji stayed in England for about a fortnight and then moved to the United States. Nivedita stayed back and took up the issue of setting up a research institute with the senior officials of the Education Department. She invited Sir George Birdwood — an important official in the British Education Department — over lunch and raised the matter. Birdwood politely refused to say that there was no one in India to head such an institute. Nivedita took the name of Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose who was then touring along with his wife Abala in England. Birdwood accepted Nivedita's proposal but expressed his inability to allow the project.

Swamiji died in 1902 and Tata died in 1904. Nivedita carried on with Swamiji and Tata's dream project. She wrote letters to scholars all over the world and sought their opinion. William James, a famous American educationist and psychologist, responded and requested her to ensure that the board of directors were taken from all the communities to give the institute a secular touch. Patrick Geddes welcomed Tata's move.

Meanwhile, Lord Curzon, who never wanted such a project to see the light of the day, called a press conference in Calcutta and said that Tata's mission had some selfish interest. Sister Nivedita slammed Curzon and wrote a letter that came out in The Statesman on July 9, 1903.

Nivedita went to the Maharaja of Mysore and convinced him to donate land for the research university which was dear to Maharaja's guru, Swami Vivekananda. Maharaja donated land at Bangalore where the centre was built.

Tata Research Institute is now called the Institute of Science — one of the premier institutes in the country. In 2013, IIS celebrated Swami Vivekananda's 150th birth anniversary and acknowledged his contribution to set it up.

Views expressed are personal