Reminiscing a ‘forgotten’ iconoclast

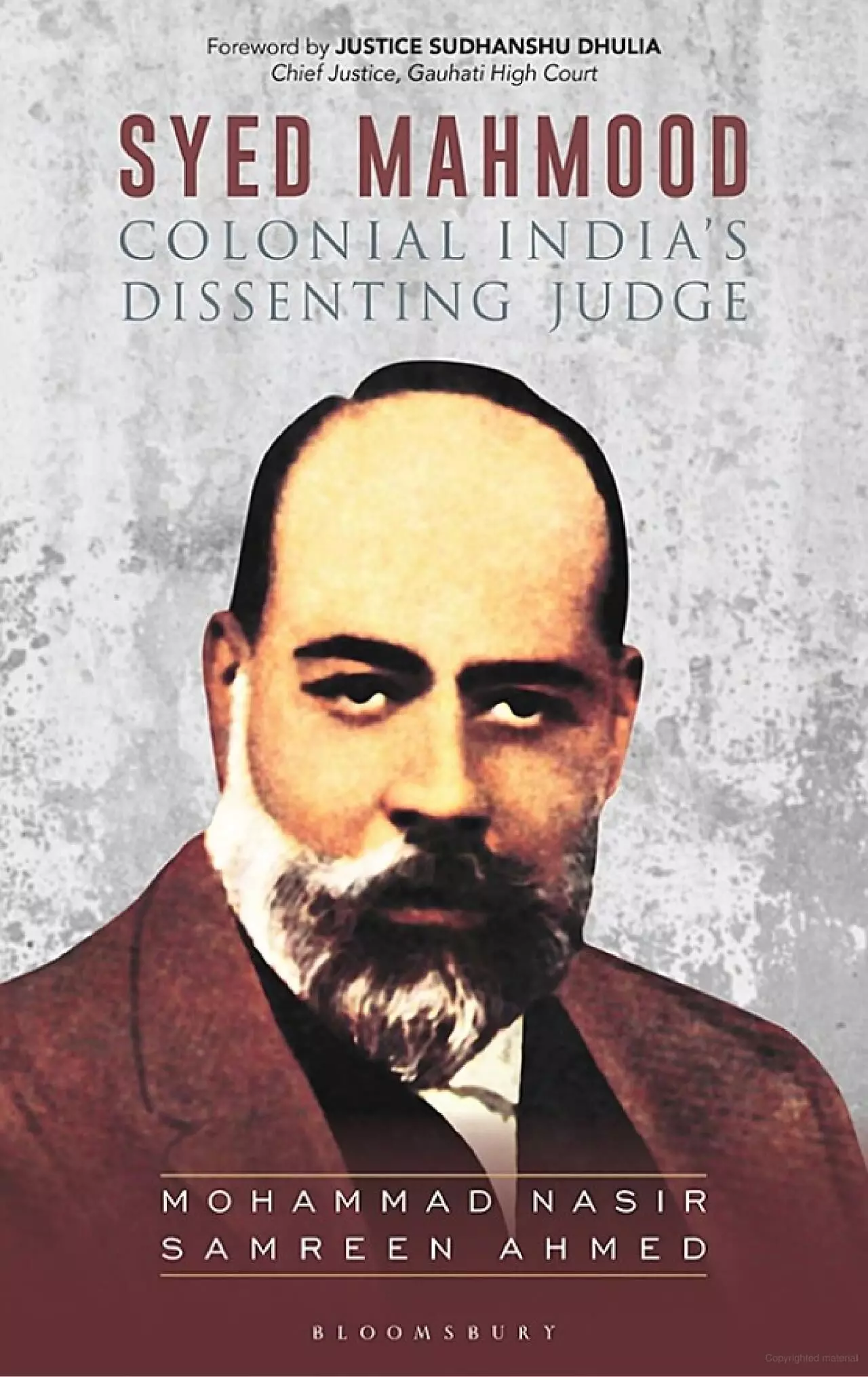

‘Syed Mehmood: Colonial India’s Dissenting Judge’ by Mohammad Nasir & Samreen Ahmed provides a well-researched chronicle and analysis of the life, achievements and the decline of India’s prominent 19th-century jurist who inculcated the idea of ‘dissent’ in the country’s judicial discourse

The book under discussion this week ‘Syed Mehmood: Colonial India’s Dissenting Judge’ by Mohammad Nasir and Samreen Ahmed is on the VoW short list, and will be discussed in the Chennai edition of VoW on December 9. Unfortunately for him, he was sandwiched, between a very illustrious father Sir Sayyad Ahmad Khan, the founder of MAO, which later morphed into AMU, and his prodigal son, Ross Mohammad who graduated from Oxford, joined Lincoln’s Inn, returned to India to set up a law practice in Patna, became vice chancellor of AMU in 1929, knighted in 1933 and became a founder of Osmania University. But Syed Mehmood (1850-1903), the first Indian Muslim to serve the Allahabad High Court as Justice between 1887 and 1893, too, left a legacy in terms of his erudite judgements, which are, till today, regarded as a beacon of jurisprudential wisdom. He is called the “dissenting judge” because he contextualised dissent within the cultural ethos and the social moorings of his countrymen, thereby putting altruism at the core of his judicial pronouncements. He shone to fame as a meteor, but was burnt early on account of his inability to temper his association with Bacchus.

It is also important to place our muse in the context of his times. He was, in his own imagination, a ‘liberal Imperialist’. But “liberal” was more important than “imperialism”, and it included the Indian’s fundamental right to tradition.

As a contemporary observer, Lieutenant Colonel Graham wrote, “When Syed Mahmood returned from Cambridge and Lincoln’s Inn as a barrister at law, his father gave a dinner to celebrate the occasion. It was remarkable as being the first dinner in these provinces at which Mohammedan and English gentlemen sat down together.” Presided over by Alexander Shakespeare (then commissioner of Banaras), toasts were raised in his honour. Barrister Mahmood, in his address, candidly spoke of his wish “to unite England and India socially even more than politically. The English rule in India, in order to be good, must promise to be eternal; and it can never do so until the English people are known to us as friends and fellow subjects, than as rulers and conquerors”. To him, both Englishmen and Indians stood on the same pedestal as subjects of the Queen of England, and the 1858 proclamation was quite clear and explicit in this respect.

No wonder then that he was deeply offended by the use of the expression ‘our Indian subjects’ by Englishmen. Digging deep into the expression, he asked: Why was a similar expression not used for the Australians, New Zealanders and Canadians. He referred to the importance of semantics as a vehicle of thought, and not merely a rule of grammar. The way a language is used is of greater consequence than a simple rule of grammar or use of idiom.

Unlike his father who maintained his distance from the INC, Syed Mehmood and his friends like Tej Bahadur Sapru, Ananda Mohan Bose and Satish Chandra Banerji, sympathised with the ideals of the incipient Indian National Congress. “Having differences in religion does not eradicate the entire influence of those matters in which Muslims and Hindus work together... Those who know me well, also know that my training and upbringing was done in such a manner and in such an atmosphere that I value national unity [hum watani] and its enthusiasm and ideas above all other ideas of humanity.”

His worldview was different from that of his father. He attributed the fall of the Mughal empire directly to the destructive intolerance of Aurangzeb, describing him as “the degrader of his ancestral heritage, the degrader of race and religion” who eventually succumbed “to the curses of the suffering devotee, to the united force of exasperated millions”. Implicit in this anger is the lingering nostalgia for what might have been, if Shah Jahan’s official heir Dara Shikoh, a philosopher-prince and an advocate of religious and social harmony, succeeded on the battlefield against his younger brother Aurangzeb

On the professional front, his legal reputation was already established early, and he seemed destined for greater honours than any Indian of his era in the judiciary. Sir Whitley Stokes, law member of the Council (equivalent to a contemporary law minister) between 1877 and 1882, noted in his book ‘The Anglo Indian Codes’: “No judgments in the whole series of Indian Law Reports are more weighty and illuminating than those of Justice Syed Mahmood”. As Vice President M Hidayatullah said of him, “his legal virtuosity, his advocacy of human rights, his sympathy for the litigant, his commitment to the principles of natural justice — ‘hear the other side’ and ‘where there is a right, there is a remedy’—won the admiration of even those who might have preferred a contrary decision’

The best part of the book is that it is detailed without being pedantic, it is sympathetic to the subject, without being hagiographic, and like Syed Mehmood’s injunction, gives the view from the other side as well. Thus, when it came to his resignation, the authors pithily comment, “The Chief Justice’s intolerance of contrary views by a native judge was the root cause of the tension. However, some of Mahmood’s errant personality traits, such as impetuous behaviour, resulted in his disappointment turning into outrage, which brought in an element of vehemence in his response.”

The writer, a former Director of LBS National Academy of Administration, is currently a historian, policy analyst and columnist, and serves as the Festival Director of Valley of Words — a festival of arts and literature.