Literary gems in Hindi

The third knowledge vertical of Valley of Words is poised to discuss three shortlisted Hindi books — Shubhra Upadhyaya’s translation of Kadambari Devi’s Suicide Note; Sheela Rohekar’s fictional masterpiece Palli Par; and Neelesh Raghuvanshi’s Sheher se Dus Kilometre Door which tells the tale of Bhopal from the unique vantage point of a cycle

This week we discuss three books in Hindi that have made it to the shortlist of the VoW Book Awards, 2023, and will be taken up for discussions at the Dev Sanskriti Vishwavidyalaya at Haridwar on September 14-15. This will be the third knowledge vertical of VoW this year – the first one on Writings for Young Adults was held at Daly College Indore on August 10, and the second at Auroville from 25-27 August in which we celebrated the 150th birth anniversary of Sri Aurobindo whose birthday, by divine providence falls on India’s Independence Day.

We first take up Shubhra Upadhyaya’s Hindi translation of Ranjan Bandyopadhyay’s Bengali retelling of Kadambari Devi’s Suicide Note. Kadambari Devi was Rabindranath Tagore’s elder sister-in-law; but they grew up together in their childhood and youth – she was nine and Rabi was seven when they first met, and were deeply involved with each other. Platonic love it was, for sure, but perhaps it was more — for this was the only relationship which defined the life of Kadambari Devi. They both grew up together in the extensive Tagore household: she was his muse, and he was her object of love, adoration, friendship and obsession. She was married to his elder brother who was ten years elder to her, and so immersed in his own world of theatre that he hardly had any time for his young bride, whom he felt was forced upon her because no ‘suitable match befitting the Tagore status’ was easily available, for the family had defied caste rules by inter-dining with Muslims. Kadambari was the daughter of an employee of the Tagore household, and therefore not treated with the dignity and respect which the other women in the family commanded.

Four months after Rabindranath married Mrinalini at the behest of his father, Kadambari Debi committed suicide at the age of 25 on April 19, 1884 by taking an overdose of opium. Rabindranath was only 23 and was desperately in love with her. It is said that she left a suicide note which was destroyed; it is this epistle which has been brought back by Ranjan Bandyopadhyay’s imagination. It was an iniquitous relationship in a patriarchal world — he was the ‘world’ for her, but for him, she was just one star in the larger firmament of his life. When Tagore went abroad to study, he wrote “beautiful women here know of their beauty as the men would shower them with complements, but beautiful women in our country don’t even know about they own beauty. Their beauty is wasted inside the four walls (women were not allowed to step outside or roam freely). Kadambari could not bear the pain of being apart from Rabi when he went abroad and tried to kill herself but failed. On his return, Kadambari and Rabindranath rehearsed for a theatre as lovers (the author of the drama

was her husband himself), in front of the extended family, but this led to pressure from the family, especially his father that he should be married off to avoid an imminent scandal. Rabi demurred, and agreed, but his marriage, he handed over all the letters that he received to her … he who had worshipped Kadambari as Radha in Vaishnav Padavali brought their friendship, love, intimacy to an abrupt end. In fact, what may have provoked Kadambari Devi to take the extreme step was the lines he found in his room:

Hetha hote jao puration, hetha nutoner khela arombho hoiyachhe…

loosely translates as “Old(past), Go away from here… Here the new sport has begun”

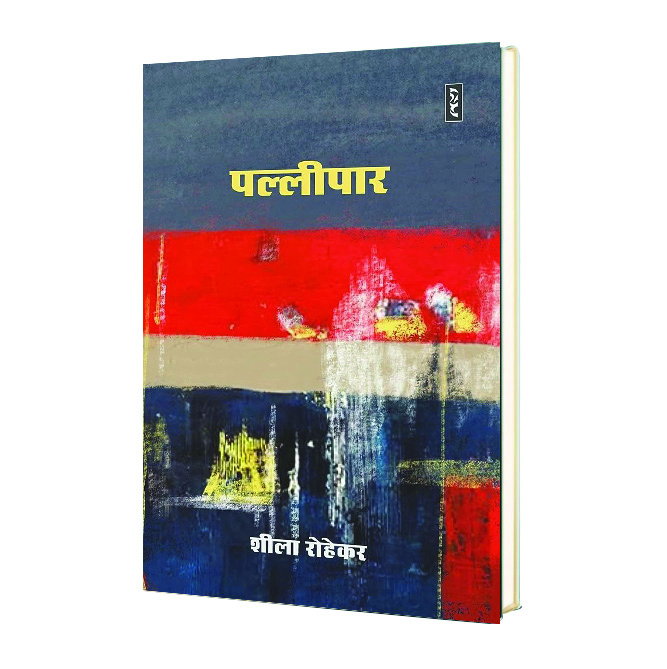

Then we have Sheela Rohekar, India’s sole Jewish writer in Hindi whose Palli Par is a fictional account on the footsteps of her award-winning work ‘Miss Samuel: Ek Yehudi Gatha,’ which gave us a world view of the life of Bene Israel community in India and the trials and tribulations in the context of communal passions that engulfed Gujarat: before, during and after the Godhra. This marked a watershed moment in Indian and Jewish writing, for only previous Hindi novel depicting the life of India’s smallest religious minority, the Jewish community, six decades ago (Meera Mahadevan’s “Apna Ghar). However, as she clarified in an interview with her interlocutor, she said: “Palli Par is not about the Jews of India. This is the story of those who lead their lives beyond the margins. This is about the poor, the marginalised, the minorities, all those who harbour stories which are waiting to be told, and more importantly, waiting to be heard. For we are all so content to live in our own respective worlds, that it is only through literary works like this one that we get an idea of life beyond the immediate horizons. Palli Par compels the reader to witness loneliness and sorrow, of being an alien in a city, of relationships that have been turned irretrievably sour, of love and longing, of being cheated and dumped in the vortex of despair, frustration and mortal fear.”

Last, but not the least is Neelesh Raghuvanshi’s Sheher se Dus Kilometre Door (Ten kilometres from the city). It is, in many ways crafted on similar lines as Palli Par. This is, in some ways, also the conversation between those of us who worked in Krishi Bhawan (Agriculture Ministry) with our counterparts in the Udyog Bhawan – each located on either side of what is now Kartavya Path, but in its earlier avatar was called the Rajpath, and before that Kings Way. We would remind them that beyond the glittering world of the National Highway with its magnificent malls, multicuisine restaurants and multiband factory outlets there was the world of agriculturists, pastoralists, herders, dairy farmers, landless workers and women-headed households who literally scrapped every dropping of gobar to make cow dung cakes on the walls of export-oriented units. However, this story is not about life on the NH, but about the outskirts of the city of Bhopal where those who are not part of the permanent settlement of the capital of Heart of India (as the tourism ad of MP calls the state) lead their marginal lives in informal settlements within the city and beyond its municipal limits. This is the tale of a town and its hinterland observed from a cycle, which is so different from the views of a city when one traverses it in an SUV or looks down upon it (literally and metaphorically) from a helicopter!

The writer, a former Director of LBS National Academy of Administration, is currently a historian, policy analyst and columnist, and serves as the Festival Director of Valley of Words — a festival of arts and literature.