Feminist tales from the Himalayas

At Auroville Literature festival, Namita Gokhale spoke about some of the outstanding masterpieces from her remarkable oeuvre, which not only breathe life into the powerful essence of feminism but also chronicle the profound mystique of Himalayan life and existence

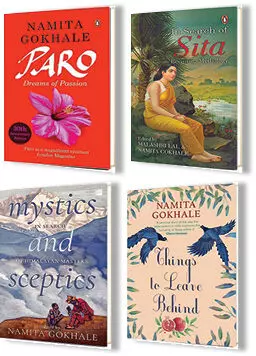

The Auroville Literature festival, with curatorial support by the Valley of Words, began on August 25 with a conversation with the prima donna of contemporary English writing in India, Namita Gokhale who has twenty-one (by the last count) books to her credit. This column covers only the books on which the forty-minute discussion was centred.

This interaction offered an insight into a very wide range of issues: from life in the Kumaon hills around 1857 in her masterpiece ‘Things to Leave Behind’ to life in the early seventies of the emerging Indian middle class coming to terms with a new way of popular writing with an intermixture called ‘Hinglish’. The sexual assertion and agency of women comes alive in ‘Paro: Tales of Passion’ as well as her alter ego ‘Priya: In Incredible Indyaa’ who in her own ways breaks many a taboo, but does not meander off the course as Paro does. In The Blind Matriarch, we look at the life of an extended joint family with separate kitchens and apartments in the same building during the Covid period. While ‘Things to Leave Behind’ as also ‘The Book of Shadows’ and ‘A Himalayan Love Story’ are set in her native Kumaon, a region she knows like the palm of her hand, The Blind Matriarch, Paro and Priya are set in the New Delhi inhabited by what is now called the ‘Khan market gang’. Then we have the Jaipur Journals which discusses the lives, loves, flirtations and frustrations of the very diverse cast of characters who are participating in the Jaipur Literature Festival, of which she is a founder. Except in the Jaipur Journals where men also exercise some salience, most of her characters – from Tiltorama or Tillie in Things to Leave Behind, or Paro or Priya or Matangi Ma in The Blind Matriarch – are all powerful women who exercise a powerful agency even in an ecosystem which is still patriarchal.

For me, personally, most striking character is that of Tiltorama or Tillie of ‘Things to Leave Behind’ whose divergence from the ‘normal’ begins early on when the diktat of India’s slow crawl towards Independence delays her marriage, allowing her access to a sliver of education and agency. For all her feminist inclinations that are fuelled by her admiration of Pandita Ramabai and the news she devours from Almora Akhbar and Almorah Annals, she is unable to translate her unconventional thoughts into independent action: whether it relates to walking freely outside her home or ensuring a proper education for her daughter. It is through her that Gokhale highlights the travails of independent-minded women in 19th century India. We also get to see a microcosm of Kumaoni life where the locals have compartmentalised Britain and India like cheese and chalk, but are also surprisingly compliant to the whims of their colonisers. They meekly accept the fact that they will walk only on the Lower Mall Road, reserved for dogs, servants and Indians.

They resist disclosing the location of the sacred lake of “Naineetal”, where Sati’s eyes have fallen, but offer little confrontation when the British take control of it. But they’re also practical enough to collaborate with the colonial master, albeit on terms that are decidedly unequal.

We now come to her non-fiction and edited books. ‘Mountain Echoes: Reminiscences of Kumaoni Women’ is a book of oral biography, that explores the Kumaoni way of life through the lives of four women: her aunt Shivani, a Hindi novelist, her grandmother Shakuntala Pande, Tara Pande and Jeeya (Laxmi Pande). As she herself confessed in the interview, she had not read much of Shivani in her growing up years, as Hindi literature was not the genre to which young people who studied in convents and grew up in cantonments or civil lines were exposed. It is only in her later years that she read a lot of literature in Hindi, as well as translations from writers in the many languages of Bharat. This perhaps explains why and how she conceptualized and hosted the Doordarshan show ‘Kitaabnama: Books and Beyond’ which became the precursor and prototype to the growing trend of literature festivals in the country.

The next was ‘In Search of Sita’ — a work she has coedited with Malashri Lal. Inspired by her visit to Sri Lanka where she made a mental note of what Sita would have felt like in captivity in the Ashok Vatika in the golden city of Lanka. The volume presents essays, conversations and commentaries that revisit mythology besides reopening the debate on her birth, exile, abduction, tryst with fire, the birth of her sons and, finally, her return to the earth: offering fresh interpretations of this enigmatic figure and her indelible impact on our everyday lives. While the Valmiki and Tulsi Ramayana deify her, Bangla, Kannada and Odiya versions show her as a woman whose life, love, sacrifice and assertion connect her with the timeless predicament of the daily lives of women in our country. While the Bollywood and soap operas focus mainly on sacrifice, self-denial and unquestioning loyalty, the authors draw our attention to Janaki, who symbolized strength, who could lift Shiva’s mighty bow, who courageously chose to accompany Rama into exile but refused to accept the humiliation of a second trial. However, one thing is certain: she was certainly not Mrs Ramachandra Raghuvanshi. Jai Sia (Sita) Ram is the preferred greeting in the Hindi heartland. The Ram Durbar which adorns the sanctum sanctorum in all Vaishnav temples is never complete without her.

And finally, the discussion veered to the Himalayas: mountains which speak to her, tell her when they are angry, and envelop her in ecstasy on other occasions. In her anthology ‘Mystics and Sceptics: In search of Himalayan Masters’, we have a very diverse set of 25 contributors who range from spiritual savants like Paramhansa Yogananda (whose best-selling autobiography of a Yogi has sold over five million copies) to doctoral students, poets, civil servants, diplomats, cultural theorists, anthropologists, translators, film-makers, opera singers, painters, psychologists and dreamers drawn from diverse geographies – almost all the regions of India, Bhutan, Nepal, the UK, the USA, Australia and Tibet. We understand the many different worlds – from the travels of Guru Nanak to those of Rahul Sankrityana, the connect of Nicholas Roerich with the Himalayas, as well as the sacred traditions of the dhuni and chimta, the shakti peeths in the Himalayan region, trance runners of Tibet and Bhutan and the Khasi rituals of divination and prophecy.

It is not without reason that she starts this volume with a few words from the 25th verse of the tenth Chapter of the Bhagwad Geeta when Lord Sri Krishna says:

Of the great sages, I am Bhrgu, I am Om of the Transcendent, among chants know me as the repetition of the Holy Name, and amongst all things immovable (and firm), I am the Himalaya.

The writer, a former Director of LBS National Academy of Administration, is currently a historian, policy analyst and columnist, and serves as the Festival Director of Valley of Words — a festival of arts and literature.