A glimpse into moral quandaries

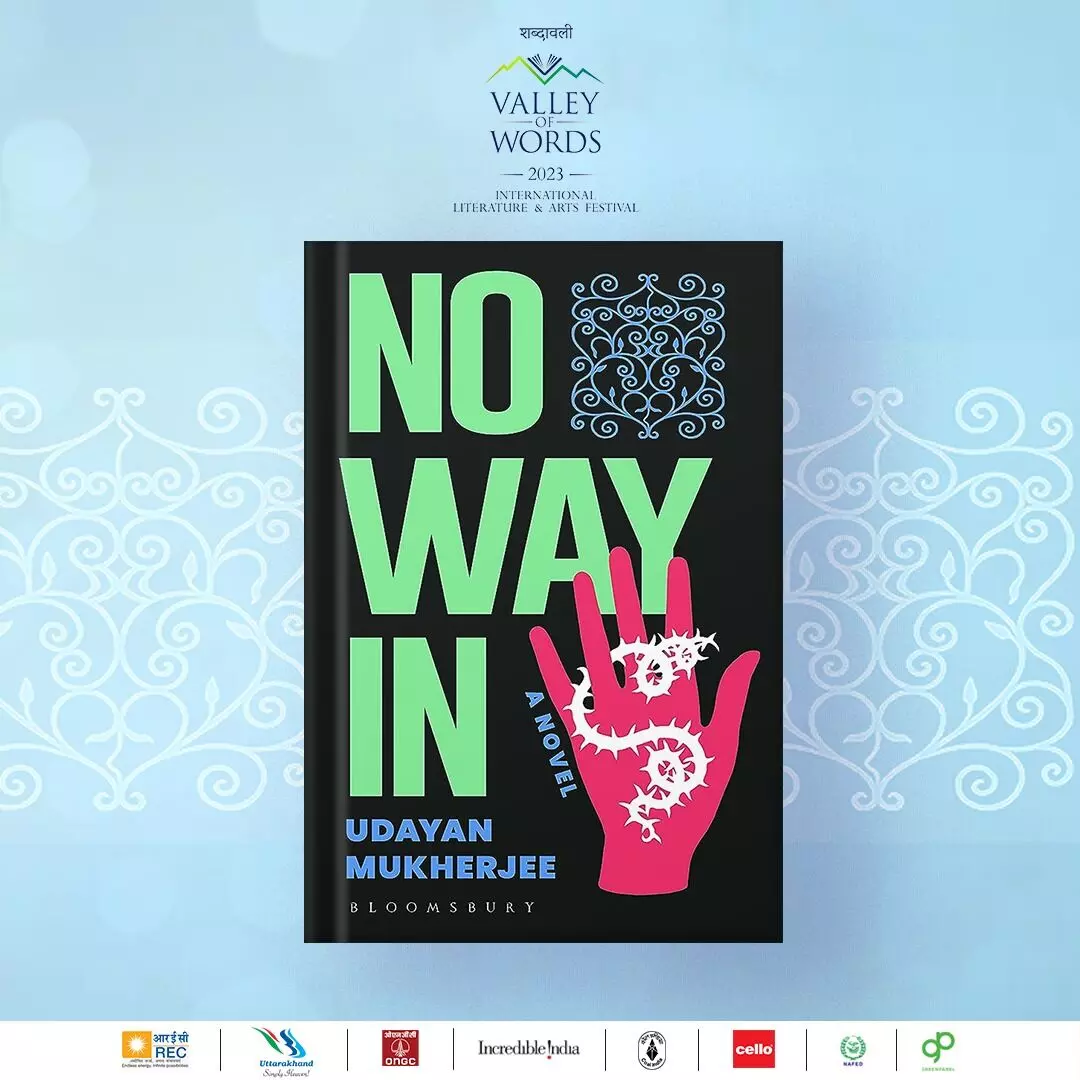

Selected as the best work in fiction genre for the Valley of Words Award, Udayan Mukherjee’s ‘No Way In’ explores the unique relationship between two children, characterised by structural inequality, to provide an insight into the political, cultural, and social life of Kolkata wherein ideological pretentions had given way to politics of identity—creating ethical dilemmas for the common masses

There are many ways to read Udayan Mukherjee’s ‘No Way In’ which has been selected as the best work in the genre of fiction for this year’s Valley of Words (VoW) Award. At one level, there is a superficial similarity with Arvind Adiga’s ‘The White Tiger’ in which those who work for prosperous Hindu families have to change their identities to secure their jobs – as drivers, maids, office boys and domestic helps. At another level, it is the story of clash of cultures within the world of the upper middle-class Bengalis – those who live in Alipore and are inheritors of old wealth, and are safely ensconced in their world of art, poetry and literature, and those who have to run commercial establishments in which class, caste and denominational conflict come to the fore. The former is the abode of the very refined Ila from the Mookerjee household which lives in Alipore (the best address in the City of Joy). It comprises judges, jurists, professors and art aficionados: so very different from that of Rana Banerjee of Jol Pori on the Sarat Chandra Avenue in South Kolkata. Rana runs a factory, faces union trouble as competition from China takes out his frustration at all whom he can prey upon. But this hemisphere is so different from that of those who work for both the Mookerjees and the Banerjees – that of Rafiq and Fatima, Ratan, Bishal and Kusum who eke out a living working for them.

But for me, this is the story of Dinu who is twelve and Shubho who is two years younger. Both live on the same premises, but have a unique relationship. While Shubho is the scion of the family, Dinu/Dinesh/Danish is the son of Saba/Sabita the maid-cum-cook in the house who has changed her identity after the gruesome riots in Assam where cops had looked the other way when the orgy of mob violence had blood spill out onto the street as well as the steams. Shubho adored Dinu, and vice versa, and though they could not be friends or brothers in the conventional sense, they were the world to each other. Shubho could sense the inequity in their relationship, he strives in his own ways to ensure that Dinu got Complan with his milk, and also shared his goodies with him. While Ila was supportive of this bond, Rana would invariably let off his temper at the smallest pretext, and Saba/Sabita realised that too much proximity was good for neither: Lines had been drawn – boundaries which ought to have been there to begin with, Sabita reckoned but were crossed on account of Ila’s kindness, and Shubho’s affection. it had taken one incident to shake off that illusion. When Dinu/Danish is asked to be part of a plot to kidnap Shubho, he breaks down — both physically and emotionally. Saba/Sabita has to leave the Banerjee household for Sahibabad in Delhi to find employment and livelihood elsewhere.

Why did Udayan write this novel, and not something else? In an interview with Devapriya Roy, he says that he wrote this novel because he wanted to write about India in the first two decades of this century. What is unfolding in India today, is only possible because of certain divisions and fault lines which lie at the core of our society; it has only needed an agent to bring it to the surface. Therefore, to locate the story within a traditional Bengali household, at a juncture when sweeping changes are transforming the country’s socio-political landscape, was something I wanted to work with. Equally, the themes of communal violence and migration triggered by it, both such ever present features since Independence, were issues that were important to weave in. In that sense, the macro came first and the micro was invented for the narrative vehicle. But as with most novels, once the first page is written the characters and the story takes over, and themes/ideas only become tools in their hands.

In fine, this is a wonderful novel to get an insight into the political, cultural, and social life of Kolkata a few years after the Communist Party was booted out in a fierce electoral contest. Ideological pretensions had given way to the politics of identity, and the political contenders played their sinister designs even as the common woman and child were placed in dilemmas well beyond their control.

The writer, a former Director of LBS National Academy of Administration, is currently a historian, policy analyst and columnist, and serves as the Festival Director of Valley of Words — a festival of arts and literature.