Towards a mature bonhomie?

In the new Asia-centric world order, India and China should bring in greater consistency in their bilateral and multilateral relations for a peaceful and multipolar Asia-Pacific region

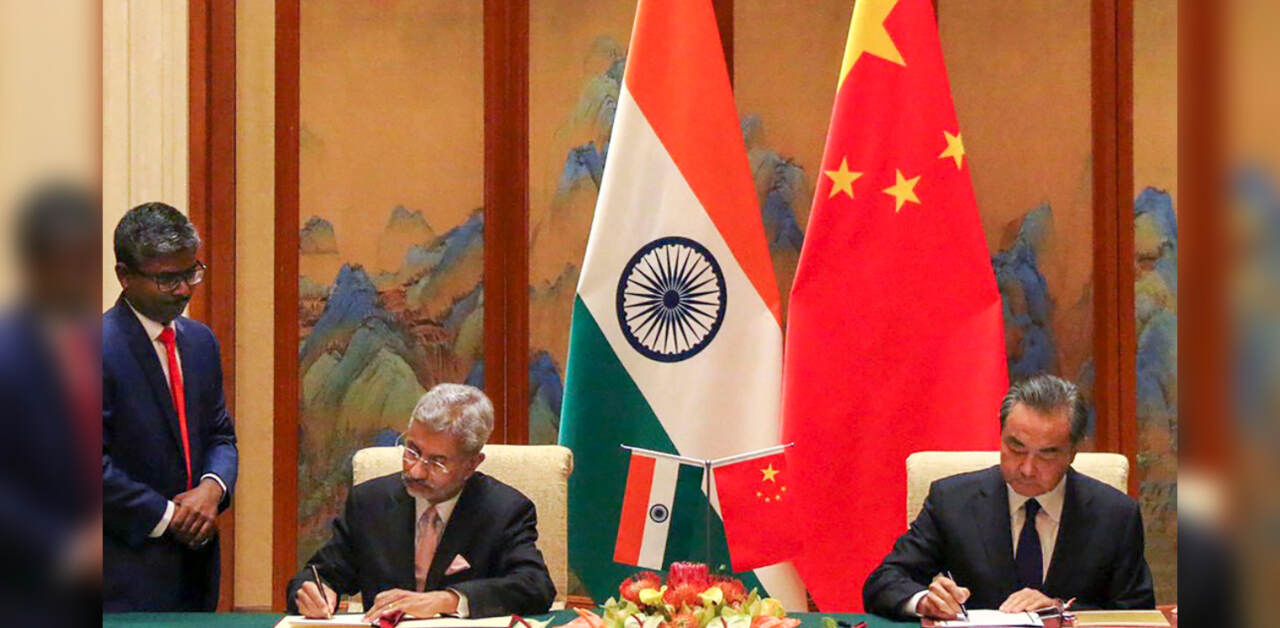

During his visit to India during March 24-25, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said, "China and India should work together to promote peace and stability around the world". He emphasised that the two sides should "put the differences on the boundary issue in an appropriate position in bilateral relations, and adhere to the correct development direction of bilateral relations…China does not pursue 'unipolar Asia' and respects India's traditional role in the region. The whole world will pay attention when China and India work hand in hand." Furthermore, in another statement, China's foreign ministry said, "Wang Yi called for transitioning the border issue from a state of emergency response to normal management as soon as possible". Indian and Chinese foreign ministers "agreed to speed up the resolution of remaining issues, properly manage the situation on the ground and avoid misunderstandings and miscalculations". This was the highest level of engagement between the two countries since a deadly border clash in 2020 soured the ties.

Reacting to this, India's Foreign Minister S Jaishankar said, "I was very honest in my discussions with the Chinese foreign minister, especially in conveying our national sentiments. The frictions and tensions that arise from China's deployments since April 2020 cannot be reconciled with a normal relationship between the two neighbours", reported Reuters.

This not-so-pleasant exchange of words between the two ministers has taken place when both India and China have agreed upon the importance of an immediate ceasefire, as well as a return to diplomacy amid the Ukraine crisis. Both India and China consider Russia a friend and have rejected the Western calls for condemnation of Russian invasion of Ukraine, which Russia calls a "special military operation". In this piece, we shall discuss why India needs a more matured China policy.

The common basis of India-China relationship

The 'grand national narrative' at the heart of modern China and India is the focus on economic development. China and India represented roughly a quarter of the global economy till 1800 but became peripheral during colonial times — shrinking from a combined 50 per cent of the world's economy in 1820 to around 12 per cent at the time of independence. The dominance of this narrative generates convergence of views and, from time to time, even cooperation. Both India and China advocate the reformation of global economic institutions. Being partners in the New Development Bank (NDB), they share a common vision for multipolar global order.

On global climate governance, both strongly support the principles of climate justice and common but differentiated responsibilities. They also put great emphasis on the responsibility of developed countries to deliver on their promised Green Fund contribution. This was evident at COP26 where India opposed the majority proposal on banning coal, advocating for the 'phase-down' of coal instead of a complete 'phase-out'. What's fascinating is that India's best partner at the COP26 in support of its position was China. This alignment has been built on years of cooperation on the coal question.

Trade and investment

Interestingly, in the midst of the pandemic and global tensions, trade between China and India has been booming. India's exports to China rose by 26 per cent to USD 21.18 billion in 2020-21 from USD 16.75 billion in 2018-19. However, the imports from China have exhibited a declining trend from USD 70.31 billion in 2018-19 to USD 65.21 billion in 2020-21. India's Minister of State for Commerce and Industries said in the Parliament that India has made sustained efforts to achieve a more balanced trade with China, including bilateral engagements to address the non-tariff barriers on Indian exports to China and measures against unfair trade practices. He further added that the trade deficit with China stood at USD 44.02 billion in 2020-21 as against USD 53.57 billion in 2018-19, reported Business Standard.

India has also started to remove restrictions on Chinese FDI in a phased manner. Restrictions were imposed in April 2020 after skirmishes along the border. Prior to these restrictions, Chinese investors had become a mainstay in India's start-up ecosystem, having deployed USD six billion over the previous two years.

BRICS trade

Though India has opted out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) — a Chinese initiative — it remains an important member of BRICS — a group of large emerging economies comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. In 2019, while addressing the 'Leaders' Dialogue with BRICS Business Council, Indian Prime Minister said, "Till the next summit, a roadmap for achieving USD 500 billion intra-BRICS trade target should be drawn up by the BRICS Business Council". This shows India's commitment to building a more robust intra-BRICS trade relation. However, as far as the numbers go, as of 2017, the percentage share of intra-BRICS trade to its global trade was just 10.61 per cent. India's share of intra-BRICS trade in its global trade is higher at 19.32 per cent but it is still lacking given the trade potential between the five countries. India's total trade with the BRICS countries in 2018-19 stood at USD 114.1 billion; a majority of this was because of its bilateral trade with China which stood at USD 87.1 billion.

The first BRICS Sherpas meeting of 2022 was held virtually on January 18-19 under the Chinese chair with the members thanking India for its BRICS chairmanship in 2021. China has proposed to host the 10th BRICS S&T ministerial meeting and senior officials meeting in September 2022. The meeting theme would promote open, inclusive and shared science, technology, and innovation. On the sidelines of the ministerial meeting, an exhibition showcasing outcomes of successful projects supported under the BRICS Framework Programme (2015-2022) will be organised. India will host five events in 2022 — BRICS Start-ups Forum; Working Group Meetings on Energy; Biotechnology & Biomedicine; ICT & High-Performance Computing; STIEP (Science, Technology, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Partnership) Working Group Meeting and the launching of BRICS innovation launch pad as a microsite (Knowledge Hub), as per discussions at the 15th meeting of the BRICS Science Technology Innovation (STI) Steering Committee on 17th January 2022.

It is apparent from the above that India has accepted China's leadership position in BRICS where it controls nearly 75 per cent of intra-BRICS trade. In addition to this, India's growing bilateral trade with China is clearly noticeable. Against these realities, India's decision to opt out of the RCEP, and show cold shoulder to the Chinese Foreign Minister during his recent visit, reveals the inconsistencies between India's declared policy towards China and its actual practice.

QUAD in crisis

After India decided to opt out of the RCEP in November 2019 (immediately after the Indian PM returned from his trip to the USA), the defunct Quad was revived again. The primary objective of the Quad – a strategic alliance between India, Australia, Japan and USA — was to contain China in the Indo-pacific region. But the Russia-Ukraine war has created fissures within this group. There would definitely be something wrong with the Quad if it starts discussing a European war and downplays the belligerence of the Chinese authoritarianism in the Indo-Pacific region — and this is exactly what Biden is imposing on the Quad. As per a report by News18, for the Biden Administration, the Quad is less about containing China or holding it accountable for its excesses than about exercising control over the three members, which happen to be powerful democracies and formidable economies whose views matter, certifying his diplomatic mastery before the American audience.

Arguments in favour of joining RCEP

Growing influence of China in Indian and intra-BRICS trade has motivated a section of Indian policymakers to argue in favour of joining the RCEP. Crisis in QUAD has strengthened their argument. RCEP — the world's largest trade agreement, including China and 14 other Asia-Pacific nations — came into effect on January 1, 2022. It may also be noted that RCEP practically comprises ten-member ASEAN countries (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) plus China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. India pulled out of the pact in November 2019 after talks failed to address its concerns over issues like rules of origin, opening up of services etc. There were also fears of the flooding of Chinese imports into Indian markets.

Conversely, one school of policymakers believes that if it's not China, it'll be some other technologically advanced country flooding our markets. We need to focus on upgrading the domestic capability and be competent on our own. According to these policymakers, we were always too paranoid with the idea of China using RCEP to enter through the backdoor. The assumption that by not joining RCEP, we would deprive China of tariff concessions and other measures is wrong. India still has a large trade deficit with China, reported The Print.

Another argument in favour of joining RCEP is the need for FDI. A study by Manjiao Chi (February 2022, ESCAP) reveals that the merits of RCEP investment facilitation provisions, with few legislative changes, capacity building and implementation efforts, may help fully realise the potential of the RCEP investment in promoting sustainable development among its member nations.

Areas of concern

Two major sectors which may get adversely affected if India decides to join RCEP Free Trade Agreement (FTA) are agriculture and micro small & medium enterprises (MSMEs).

Agriculture is a very vulnerable sector because of its relatively low efficiency globally. A recent study by Dhar and Kishore (2021), discloses that a huge labour force is still engaged in agricultural activities though their productivity is very low. In 1950-51, the share of agriculture in GDP was 45 per cent and 70 per cent of the nation's workforce was dependent on this sector. After seven decades, the corresponding shares are 15 per cent and 42 per cent. In 2019, India's rankings in terms of wheat and rice yields were 45 and 59 respectively. As per FAO data, in 2019, the yield of rice (tonnes/hectare) for Australia, the USA, China, and India were, 8.8, 8.4, 7.1 and 2.7 respectively. In the case of wheat, the productivity (tonnes/hectare) for Ireland, the UK, China, and India were 9.4, 8.9, 5.6, and 3.5 respectively.

The overall expenditure on agriculture research was virtually stagnant in India, contrary to the case in China that witnessed a rapid trend in this regard. Further, India's agricultural research spending, as a share of its value-addition in agriculture, saw a declining trend, while for China, the trend was the opposite. In terms of productivity of many agricultural products, RCEP members like Thailand, Myanmar, and New Zealand are more competitive than India. Unless adequate safety measures are incorporated in the agreement to protect the interests of millions of small and marginal farmers, India may face a serious food security problem, as is observed in Sri Lanka. Alternatively, the Government of India must spend heavily in the farm sector towards infrastructure development and agricultural research in order to improve the competitiveness of Indian agricultural products. It is a long-term strategy that needs elaborate planning and political will of the state.

MSME is another susceptible sector. This sector contributes around 30 per cent to India's GDP, employs about 110 million people, constitutes nearly 40 per cent of total exports, and more than half of these are located in rural India. But MSMEs are confronted with several financial constraints. Limited awareness and technical wherewithal, unsupportive regulatory regime, and complex environmental norms create further challenges for the MSMEs.

In India, MSMEs are categorised on the basis of investment in equipment and annual turnover. By definition, this sector includes enterprises with turnover ranging from a few lakh rupees to Rs 250 crores. Thus, a subsidiary of a transnational corporation may also be considered as a medium enterprise if its turnover does not exceed Rs 250 crore per year! This vast diversity of MSMEs makes it difficult for policymakers to make singular policies for all categories of the MSMEs.

The last Economic Census of India (2013) reported that during 2013-14, 131.29 million persons were employed in 58.5 million establishments. The distribution of establishments by the size of employment reveals that around 55.86 million establishments (95.5 per cent) were having 1-5 workers, around 1.83 million establishments (3.13 per cent) were having 6-9 workers, while 0.8 million establishments (1.37 per cent) employed 10 or more workers. It clearly indicates that enterprises with less than ten workers constituted more than 98 per cent of overall Indian enterprises. There is little reason to believe that this distribution of enterprises, done on the basis of employee size, has changed much during the last eight odd years.

It has been observed that only around 16 per cent of MSMEs are being financed by the formal banking system in India. Under such a pathetic situation, thousands of micro and small enterprises will find it difficult to face global competition and challenges of climate regulations. The lack of available information on climate finance and low financial literacy levels limit their understanding of how their businesses could benefit from climate finance. They would not know, for instance, that leveraging climate finance can help them manage some of their business risks, or that availability of newer, cost-effective technologies can reduce carbon emissions.

Experiences with past FTAs

The three major regional trade agreements that India has entered into with its Asian partners, namely (i) India-South Korea Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (2009), (ii) India-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (2011), and (iii) ASEAN-India FTA (2009) have gone against India. In all the cases, India ended up as a net importer. For example, in 2019-20, India's import from ASEAN amounted to USD 55.37, compared to the exports of USD 31.55 to the said bloc.

As per a report by The Hindu, the Indian government is in discussion with the ASEAN and other trade partners for initiating the review of FTA (free-trade agreement) in goods to seek more market access for domestic products. On this issue, the Minister of State for Commerce and Industries has informed the Parliament that "representations from industry are received from time to time on the surge in imports from ASEAN countries, Japan and Korea, which are examined in consultation with the concerned administrative ministries. They are taken up with the respective trading partners under the existing institutional mechanism enshrined in the respective free trade agreements". The minister further noted, "FTAs have inbuilt provisions to check any misuse of the FTA concessions, which inter-alia include strict compliance of the Rules of Origin, checking mis-declaration, if any, and taking trade remedial actions".

Conclusion

At present, India and China are in a 'love-hate relationship' which needs to be steadied for the benefit of these two great civilisations where over 35 per cent of the global population resides. As the power centre of the global economy and politics has shifted to Asia, India must play an important role in the development of a multi-polar Asia-Pacific.

Once, India was the leader of the 'non-alignment' movement. As a FTA partner of ASEAN, India should follow the policy of 'ASEAN-Centrality' — a synonym to ASEAN as the leader, driver, architect, institutional hub, vanguard, nucleus or fulcrum of regional cooperation, for a peaceful and multi-polar Asia-Pacific region.

Before committing to any new FTA, including RCEP, the Government of India must review all the existing agreements and take corrective measures wherever necessary.

Views expressed are personal