Delusional deduction!

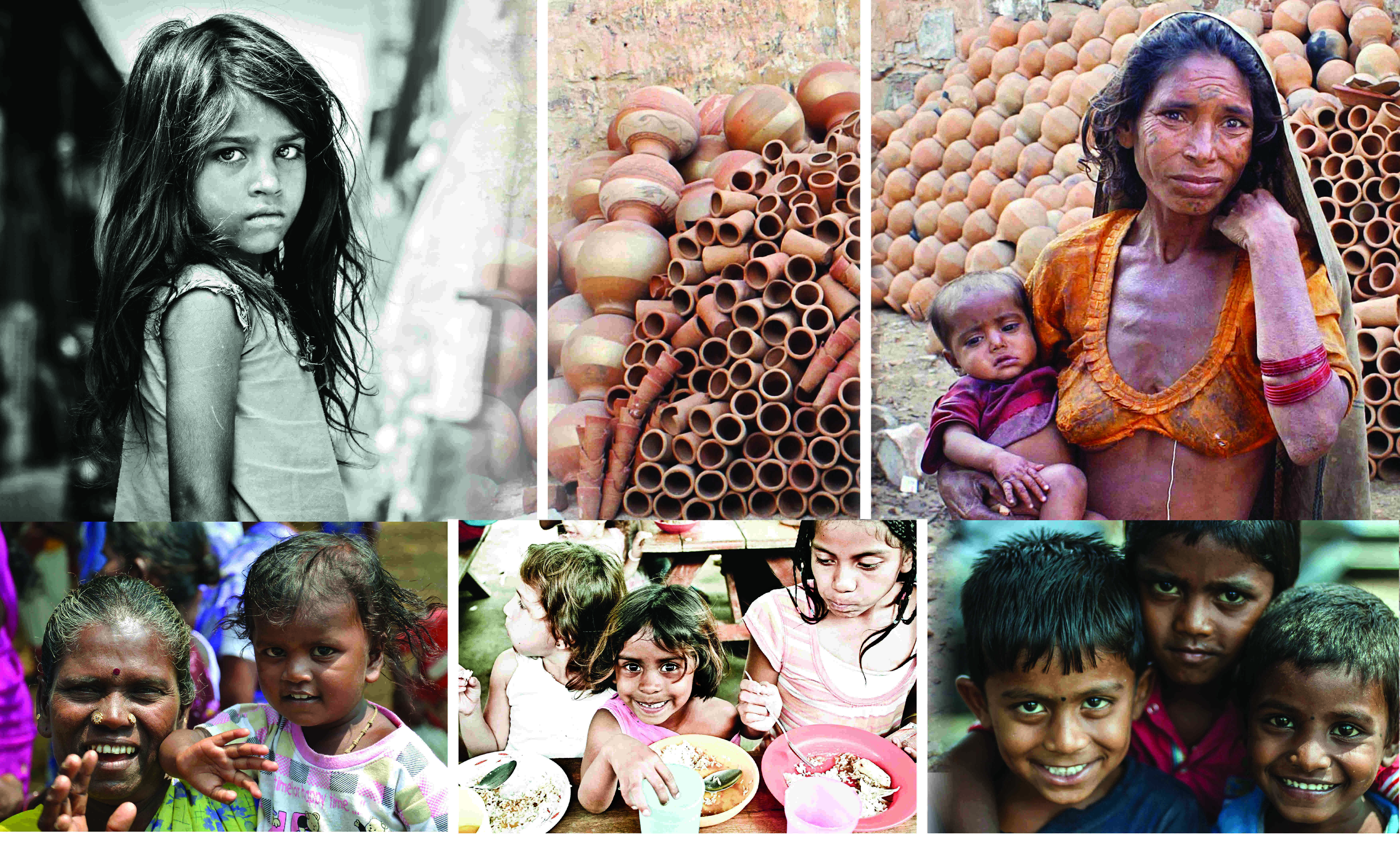

IMF’s rosy estimate of abysmal poverty in India is not just in sharp contradiction with more realistic findings of other prominent institutions and researchers, but also ignores the multidimensional nature of the malaise

A recent IMF Working Paper — 'Pandemic, Poverty, and Inequality: Evidence from India' (April 2022) — claimed that India was nearly free from extreme poverty in 2020 and inequality was at the lowest point in the past 40 years. IMF executive director Surjit Bhalla and co-authors of the paper have estimated that extreme poverty (less than Purchasing Power Parity of USD 1.9 per person per day) in India was 0.8 per cent in 2019 and it remained at that level even during the pandemic year 2020.

The paper presented estimates of poverty and consumption inequality in India for each of the years from 2004-5 through the pandemic year 2020-21. These estimates included, for the first time, the effect of in-kind food subsidies on poverty and inequality. Extreme poverty was as low as 0.8 per cent in the pre-pandemic year 2019 and, according to the authors, food transfers were instrumental in ensuring that it remained at that low level in the pandemic year 2020. Post-food subsidy inequality at 0.294 was very close to its lowest level at 0.284 observed in 1993/94. To reach a 'reliable' poverty estimate, the authors monetised the subsidised food grains and added them to people's income basket. Thus, Bhalla and his co-writers have 'assumed' in-kind transfer as cash transfer, claiming that this was a "reasonable assumption given that households could always sell the subsidised food grains in the open market."

Contrary to these findings, the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs on Sustainable Development reported that globally, COVID-19 has led to a rapid rise in 'extreme poverty' in a generation. According to them, an additional 119-120 million people were pushed back into extreme poverty in 2020. The global poverty rate is projected to be around seven per cent by 2030 — thus missing the target of eradication of extreme poverty by that year.

It will be naïve to believe that India — which has seen large-scale reverse migration of millions of people who had to walk hundreds of miles to return back to their homes during a sudden lockdown, and with the economy indicating all the alarming signals of stagflation for a long time — fits into the story as claimed by Bhalla et al.

Though the IMF paper carried the usual disclaimer — "working papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate", it has created a tremendous sense of national pride in the 75th year of India's independence.

Reacting to this finding which contradicts the crude reality of the common man's struggle for existence during and after the pandemic period, Richard Mahapatra, a noted social scientist,

commented that Bhalla's assumption defied any imagination. And to declare an end to extreme poverty in India based on this assumption was simply a 'methodical madness'. Based on his field experiences, Mahapatra also mentioned that at the household level, the subsidised food grains have enabled people to meet food requirements but there is no certainty of income, particularly during the pandemic time. Poverty is not just a measure of hunger. It has many other dimensions.

Assessing poverty is not new in India. The history of poverty estimation in India dates back to as early as 1901 when Dadabhai Naoroji estimated poverty in the country based on the cost of a subsistence diet. In 1938, the National Planning Committee suggested poverty line estimation based on living standards, followed by the Bombay Plan in 1944. Addressing and ending poverty has been a part of national agenda since independence. Various committees, working groups and scholars — including the working group of 1962, Dandekar and Rath in 1971 and the YK Alagh task force in 1979 — were engaged in estimating the headline poverty to inform public policy. Similarly, the expert groups under Lakdawala (1993), Tendulkar (2009) and the Rangarajan Committee (2014) undertook the exercise of estimating monetary poverty.

Poverty has many dimensions

The resolution of the United Nations General Assembly on September 25, 2015 has established 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The very first goal — end poverty in all its forms everywhere — in its entirety, is multi-dimensional in nature. While the target 1.1 seeks to eradicate extreme poverty, measured as people living on less than USD 1.25 a day (subsequently increased to USD 1.9/day) by 2030, the target 1.2 aims at reducing multidimensional poverty (based on national definitions) to half by 2030.

In 2021, which was the sixth anniversary of the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals, the Government of India released the 'National MPI: Baseline Report & Dashboard'. It was launched by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog) for realising the SDGs — particularly the target 1.2 of the 2030 Agenda which specifically focuses on addressing poverty in all its dimensions.

India's national MPI measure uses a globally accepted methodology developed by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) — which have been key partners in ensuring the public policy utility and technical rigour of the Index. Importantly, as a measure of multidimensional poverty, it captures multiple and simultaneous deprivations faced by households. This baseline report of India's first-ever national MPI measure is based on the reference period of 2015-16 of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS). The national MPI has been constructed by utilising twelve key components which cover areas such as health and nutrition, education and standard of living.

It may be mentioned that the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) has been used by the United Nations Development Programme in its flagship Human Development Report since 2010 and is the most widely employed non-monetary poverty index in the world. It captures overlapping deprivations in health, education and living standards and complements income poverty measurements because it measures and compares deprivations directly.

In this context, it is claimed that a national MDI for India will enable estimation of poverty not only at the level of the states but also for all the 700 plus districts across twelve indicators, capture simultaneous deprivations and indicator-wise contribution to poverty, and most importantly, will facilitate the formulation of sectoral policies and targeted interventions which contribute towards ensuring that "no one is left behind". The national MPI is constructed directly from each person's profile of deprivations across each indicator, built from a single household survey that captures the data on all the indicators.

Few crude facts

A World Bank paper — jointly authored by economists Sutirtha Sinha Roy and Roy van der Weide — on India's extreme poverty, contradicts the IMF study of Bhalla et al. The Bank's working paper, 'Poverty in India Has Declined over the Last Decade but Not as Much as Previously Thought', states that "rural and urban poverty dropped by 14.7 and 7.9 percentage points during 2011-2019". The report mentions that the extreme poverty in India was 12.3 percentage points lower in 2019 than in 2011. According to the data presented by the World Bank, the poverty headcount rate has declined from 22.5 per cent in 2011 to 10.2 per cent in 2019, with a major decline witnessed in rural areas of the country. While the poverty levels went down to 11.6 per cent in rural areas of India in 2019, the level of urban poverty stood at 6.3 per cent during the same time period. The poverty reduction in rural areas was much higher as compared to that in urban areas, reports DNA.

In another report, 'Poverty & Equity Brief: India' (April 2020), the World Bank stated: "between FY 2011/12 and 2015, poverty declined from 21.6 per cent to an estimated 13.4 per cent at the international poverty line (PPP USD 1.90 per person per day). Despite this success, poverty remains widespread in India. In 2015, 176 million Indians were living in extreme poverty. In this context, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the containment measures adopted by the government are expected to increase poverty in the country."

Malnutrition is endemic in India. In 2015-16, some 38 per cent of preschool children were stunted while more than half of Indian mothers and children were anaemic. It may also be mentioned that between 1950-51 and 2010-11, the production of milk, egg, and fish had increased by 7.1, 34.4, and 11 times respectively. Nevertheless, in 2006, 43.5 per cent of Indian infants were underweight compared to only 4.5 per cent of babies in China (in 2005). This situation has not improved in the last decade or so. FAOSTAT data (2017-19) shows that with 14 per cent of its population undernourished, India lags behind emerging market peers such as Bangladesh and Vietnam, in terms of the prevalence of undernourishment (when it comes to per capita nutritional intake levels). India is also home to the largest number of undernourished (over 189 million during the triennium 2017–19), making up for over 28 per cent of the world total.

Raghunathan et al. (2020) in their paper, 'Affordability of Nutritious Diets in Rural India,' have estimated that 45-64 per cent of the rural poor cannot afford a nutritious diet that meets India's national food-based dietary guidelines. Their study pointed to the need for close monitoring of food prices through a nutritional lens, and to shift India's existing food policies away from their heavy bias towards cereals.

The question is why this dichotomy between the huge rise in food production and the deficient nutritional conditions of the citizens prevails? One simple answer is the lack of purchasing power of a large number of Indians. During the pandemic, the purchasing power of the common people further deteriorated. This dearth of purchasing power of a large section of citizens induces traders to divert huge quantities of food grains and poultry items to the off-shore market.

According to NITI Aayog's first Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) report, released in November 2021, the National MPI score of India is 0.118 — 0.08 in urban areas and 0.155 in rural areas. The report shows that 25 per cent of the Indian population is still poor.

Kerala has turned out to be the state with the lowest rate of poverty in India. As per the index, only 0.71 per cent of Kerala's population is poor. Kottayam of Kerala is the only district in India without poverty. This district has registered a zero in the recently released poverty index.

States like Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh have registered the highest poverty rates across India. These states have emerged as the 'poorest states' of the country — 51.91 per cent of the population in Bihar has been classified as poor, followed by Jharkhand (42.16 per cent) and Uttar Pradesh (37.79 per cent).

As per the real-time data from World Poverty Clock, six per cent of the Indian population is living in extreme poverty. According to Global MPI reports 2019 and 2020, 21.9 per cent of the population was poor in the country; or the number of poor was pegged at 269.8 million.

The UNDP's special report 2022 — 'New Threat to Human Security in the Anthropocene: Demanding Greater Solidarity' — mentions the following data on India.

✵ Population living with multidimensional poverty: 27.9 per cent

✵ Employment to population ratio (among persons aged 15 and older): 46.7 per cent

✵ Skilled labour force (per cent of the labour force): 21.2 per cent

Any data pertaining to India's poverty doesn't support the findings of the IMF working paper by Bhalla et al. that India had brought down the percentage of the extremely poor population to less than one per cent by 2019 and that even during the pandemic period, the incidence of extreme poverty remained the same.

Conclusion

The IMF working paper examined how the food subsidies under the National Food Security Act 2012 and the pandemic-specific relief programme, the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana, have positively impacted extreme poverty and inequality levels during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It may be recalled that Bhalla has been a staunch advocate of doing away with food subsidies and the distribution of subsidised food grains. Instead, he propagated the distribution of food stamps. He was the leader among select economists who opposed the Food Security and the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). In June 2014, he even suggested dismantling the current welfare system and adopting new approaches in order to reduce poverty and boost the country's growth rate. Now, as the Executive Director of IMF for India, Sujit Bhalla glorifies the expansion of India's food subsidy programmes and claims that it made "India poverty-free in a pandemic year". His present stand will weaken the powerful camp which lobbies for the unrestrained free market for foods including grains. This might lead to policy paralysis on this important issue.

In the coming months, what policy the Government of India formulates to achieve the SDG1 target by 2030 is to be closely watched and debated by all the major stakeholders. A holistic approach is needed to end the multidimensional poverty of the millions of Indian citizens who are suffering from this obscenity even after seven decades of attaining independence from the colonial rulers.

Views expressed are personal