Governance gridlock

The alarming rise in youth unemployment among educated graduates in India has caught the attention of poll-bound electorates, revealing deep flaws in the education system, worsened by governance disputes between Union and state governments, which can be partly resolved by shifting education back from the Concurrent to the State list

In a pre-poll survey, conducted by CSDS-Lokniti, unemployment has emerged as the top concern among the voters. 27 per cent respondents consider it as their top concern. Concern for unemployment is followed by concern for price rise (23 per cent respondents). Development ranks 3rd in the list (13 per cent) followed by corruption (8 per cent). Surprisingly, the survey reveals that non-economic issues like Ram Mandir in Ayodhya (8 per cent), Hindutva (2 per cent), India’s international image (2 per cent), and reservation (2 per cent) are not major concerns for the electorates surveyed. 63 per cent respondents have identified unemployment, price rise and development as their major concerns. This piece will briefly focus on these three issues only.

Unemployment

As per the data provided by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the unemployment rate in India decreased to 7.64 per cent in March from 8.01 per cent in February. Unemployment rate in India averaged 8.17 per cent from 2018 until 2024, reaching an all-time high of 23.50 per cent in April of 2020 and a record low of 6.40 per cent in September of 2022.

In 2022, the labour force participation rate in India was 55.2 per cent, which was lower than the world average of 59.8 per cent, and the share of unemployed youths in the total unemployed population was 82.9 per cent, which was miserably high.

On March 24, 2024, the 3rd edition of the ‘India Employment Report 2024: Youth Education, Employment and Skills’, produced by the Institute for Human Development (IHD) and International Labour Organisation (ILO), was released. The report examines the challenge of youth employment in the context of the emerging economic, labour market, educational, and skills scenarios in India, and changes over the past two decades.

Major concerns flagged in the report:

* The workforce participation rate and the unemployment rate showed long-term deterioration between 2000 and 2019 but improved thereafter. Nearly two thirds of the incremental employment after 2019 comprised self-employed workers, among whom unpaid (women) family workers predominate. The share of regular work, which steadily increased after 2000, started declining after 2018.

* Employment in India is predominantly self-employment and casual employment. Nearly 82 per cent of the workforce engages in the informal sector, and nearly 90 per cent is informally employed.

* The real wages of regular workers either remained stagnant or declined. Self-employed real earnings also declined after 2019. Overall, wages have remained low. As much as 62 per cent of the unskilled casual agriculture workers and 70 per cent of such workers in the construction sector at the all-India level did not receive the prescribed daily minimum wages in 2022.

* Due to increasing mechanisation and capital use, the employment generation in India has become more and more capital-intensive, with fewer workers employed between 2000 and 2019 than in the 1990s.

* Platform and gig work have been expanding, but it is, to a large extent, the extension of informal work, with hardly any social security provisions.

* The migration levels in India are not adequately captured through official surveys. The rates of urbanisation and migration are expected to considerably increase in the future. India is expected to have a migration rate of around 40 per cent in 2030.

* Between 2000 and 2012, employment in India experienced an annual growth rate of 1.6 per cent, but during 2012 and 2019, employment growth was nearly negligible, at 0.01 per cent.

* Employment in the agriculture sector experienced a negative growth rate during 2000–19. This trend reversed with substantial growth in agriculture during 2019–22.

* Most jobs generated in the construction sector are characterised by low wages and their informality.

* The youth population, at 27 per cent of the total population in 2021, is expected to decline to 23 per cent by 2036. Youth participation in the labour market has been much lower than among adults and was on a long-term (2000–19) declining trend, primarily due to greater participation in education.

* Youth unemployment increased nearly threefold, from 5.7 per cent in 2000 to 17.5 per cent in 2019 but declined to 12.1 per cent in 2022. The incidence of unemployment was much higher among young people in urban areas than in rural areas and among younger youths (aged 15–19) than older youths (aged 20–29).

* The youth unemployment rate has increased with the level of education, with the highest rates among those with a graduate degree or higher, and higher among women than men. In 2022, the unemployment rate among youths with a secondary or higher level of education (at 18.4 per cent) was six times greater than the persons who cannot read and write (at 3.4 per cent). And it was nine times greater among graduates (at 29.1 per cent). Educated female youths experienced higher levels of unemployment compared with educated male youths.

* Women not in employment, education or training amounted to a proportion nearly five times larger than among their male counterparts (48.4 per cent versus 9.8 per cent) and accounted for around 95 per cent of the total youth population not in employment, education or training in 2022.

* At an aggregate level, as much as 42 per cent of youths have less than a secondary level of education and only 4 per cent of them have accessed formal vocational training.

* A large proportion of highly educated young men and women, including the technically educated, are overqualified for the job they have.

* The report highlights five key policy areas for further action, which apply more generally and also specifically for youth in India: i) promoting job creation; ii) improving employment quality; iii) addressing labour market inequalities; iv) strengthening skills and active labour market policies; and v) bridging the knowledge deficits on labour market patterns and youth employment.

Reacting to the ILO –IHD Report, the Chief Economic Adviser of the Union Government confessed that the “Government cannot solve the problem of unemployment”. Nevertheless, the former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan advised that “India needs to firstly make the workforce more employable, and, secondly, create jobs for the workforce it has.” He also suggested focusing more on education and healthcare to become a developed economy.

Rising prices, falling savings and climbing household debts

In 2023, the average inflation rate was 5.49 per cent, which dropped to 5.09 per cent in February 2024. However, the inflation rate in the rural areas, at 5.34 per cent, remains 0.56 per cent higher than the urban areas (4.78 per cent), The food inflation in February stood at 8.66 per cent, a rise from 8.3 per cent in the previous month, reports Forbes. In 2023, the medical inflation in India was 9.6 per cent, which is feared to touch 11 per cent in 2024. Education inflation was around 12 per cent in 2023.

Using the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) Annual Report 2022-2023, Mehrotra and Kumar (The Wire, March 27, 2024) estimated that 24.6 per cent of the rural workforce (of 430 mn) earns less than Rs 100 a day (nominal). And about 10 per cent of the urban workforce (138 mn) faces similar circumstances. These figures underscore the persistent and extensive nature of poverty, demystifying the notion of its eradication.

The authors’ study also reveals that a significant portion of the workforce falls within the unwarranted wage bracket of Rs 100 to 200 per day. Shockingly, 17 per cent of rural self-employed and 12 per cent of regular salaried workers earn wages within this range. Moreover, the workforce, particularly in rural areas, continues to grapple with the burden of unpaid family labour (which constitutes about 22 per cent and 6.6 per cent in rural and urban workforces respectively). While till 2019 the absolute number of unpaid family labour was dropping, 40 mn were added to the unpaid family worker category of workers in just three years (2020 to 2023) in rural areas, and another 2 mn were added in urban areas.

As a consequence of high unemployment rate, rising prices (due to cost push inflation) and low wages, common men are facing tremendous financial stress. Their savings has declined to the lowest level and household debt has skyrocketed in recent times. According to financial analysts, India’s household debt levels had touched an all-time high of 40 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by December 2023, while net financial savings likely dropped to their lowest level at around 5 per cent of GDP, reports The Hindu.

Another outcome of this grave financial condition of the common man is the rising defaulting rate of credit card payments. It is reported that outstanding credit card balances soared 31 per cent to Rs 2.6 lakh crore in January amid RBI curbs. The debt-ridden households face the risk of mass impoverishment in India.

Failed development

India, arguably the third largest (measured on purchasing price parity) economy of the world, ranks 134 out of 193 countries on the global Human Development Index (HDI). All the neighbours of India (with the exception of Nepal and Pakistan) have better HDI rank. China and Sri Lanka, ranked at 75 and 78 respectively, fall under the High Human Development Category. India (134), Bhutan (125) and Bangladesh (129) are under the Middle Human Development Category.

The low level of human development could be because of India’s skewed focus on military modernisation, ostensibly at the cost of vital sectors like education and health, reported Millennium Post last week. In the Union Budget 2024-25, the Defence Ministry has been allocated Rs 6.21 lakh crore, which is the highest among all the ministries.

For example, for FY 2024-25, the budget allocated to the health sector is only Rs 90,171 crore. The health allocation at 2.5 per cent of GDP should have been Rs 8,19,000 crore, given the projected GDP for 2024-25 of Rs 3,27,71,808 crore. The National Education Policy, 2020, advocates that 6 per cent of the GDP should be spent on the education sector. This comes to Rs 19,66,309 crore, but in the current budget, education has been allocated Rs 1,24,638 crore— roughly a 7 per cent decrease compared to the revised estimate for 2023-24. The allocation for the University Grants Commission (UGC) was slashed by 61 per cent, the largest ever cut in at least five years.

In 2024, the 109th edition of the Indian Science Congress, which was scheduled to begin on January 3, was postponed. It appears that a strong ‘anti-knowledge brigade’ has been formed in India, which enjoys considerable power to destabilise the education system of the country.

Though according to a BBC report, the World Health Organisation estimated 4.7 million excess deaths—both directly and indirectly related to COVID-19—to have taken place in India, the Union Government has not taken any serious step in boosting the basic medical infrastructure of this large country which houses the largest number of the world population.

It shows the Union government’s lackadaisical approach towards securing the basic needs of its citizens—quality education and health are pushing down all the development parameters. Low HDI has put India in the vicious cycle of poverty, lack of education, poor health, low unemployment, and high debt. The cycle continues.

To get out of this mess, high-net-worth individuals have started leaving the country for a greener pasture. An estimated 6,500 high-net-worth individuals (HNIs) might have moved out of India in 2023. And the unemployed poor youths are now opting for high-risk jobs in war zones to earn their living. It is reported that 6,000 workers from India are to be taken to Israel during April-May—largest foreign contingent to Israel to replace Palestinian workers who had their entry permits revoked after Oct 7, reports The Hindu.

Observations

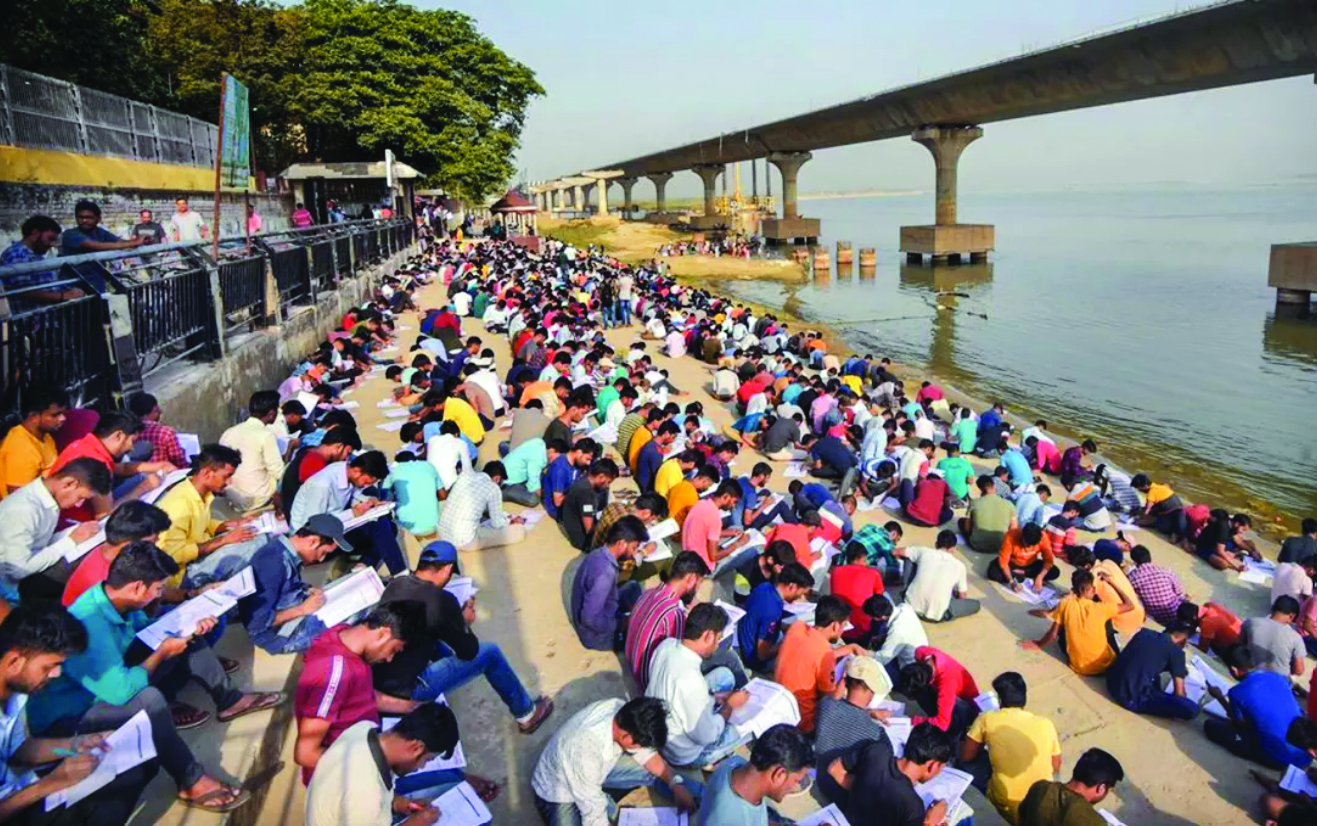

One major area of concern that has been highlighted in the ILO-IHD report is that the youth unemployment rate has increased with the level of education, with the highest rates among those with a graduate degree or higher, and higher among women than men. This observation gets strengthened when it is reported that 81,700 graduates, including 3,700 PhD-holders, applied for 62 peon posts in Uttar Pradesh Police Department. However this is not limited to the state of UP only. Same trend is observed in other states also, which indicates a serious flaw in India’s education system.

It may be mentioned that ‘education’ falls under the ‘concurrent list’ of governance, and during the last few years, major conflicts between the Union and state governments on governance issues have been observed. The recent conflict between the state education department and the office of Governor of West Bengal over the appointment of thirty two vice chancellors of the state universities is a case in point. Due to this long tussle, the academic administration of all the state universities in West Bengal has been stalled. The pathetic condition of educated unemployed youth of India strengthens the observation that ‘a divided responsibility is no responsibility’!

In other opposition-run states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, similar conflicts between the states and the Union Government on the academic administration of higher educational institutions have been reported. Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin has recently made a passionate plea for bringing education back on the State

List from the Concurrent List of the 7th Schedule of the Constitution. He argued in his Independence Day speech that the state government should have absolute control over subjects directly concerning people.

The 42nd Amendment to the Constitution through which education was moved from the State list to the Concurrent list during the 1976 Emergency is a “poisonous tree” that has borne many harmful fruits, such as the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 introduced by the Centre, the Madras High Court was told during the arguments on a case challenging the validity of the amendment.

India is a large country with the largest population in the world. The vast diversity of cultural and racial characteristics of citizens demands a customized system of education and training, depending on the requirements of the communities. A centrally managed ‘one size fits all’ policy is bound to fail in India. A decentralised education policy managed by state/local government is needed. Through constitutional amendment education should be transferred to the state list from the concurrent list.

Views expressed are personal