The Nobel Series: The Development Man

Recipient of the third Nobel for economics, Simon Kuznets’ work on national income, economic growth and income distribution made him a significant voice in academic and public policy circles alike

The third Nobel Prize in economic sciences was awarded to Simon Kuznets. Kuznets is well known for his work on economic growth and its impact on income distribution. In fact, this is the work that got him the Nobel from the Swedish Academy. Kuznets early education was in Ukraine, from where he migrated to the United States at the age of 21 years and then enrolled in the economics programme in Columbia University. He got his doctorate from Columbia University.

Main works

Kuznets is well known for three broad areas of work: a) computing national income and its components; b) economic growth and impact on income distribution and c) demographic studies. The website of the Nobel Prize gives the motivation of the prize to Kuznets thus: "for his empirically founded interpretation of economic growth which has led to new and deepened insight into the economic and social structure and process of development."

a. Computation of national income

Kuznets is better known for his work on national income and its components. Working in the 1930s, he broke down components of national income by industry, final product and by use. Working in the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) in the USA, he worked on a cross country study to find out long term trends in important macroeconomic indicators such as capital-output ratio, savings, investment, consumption etc. One of the important findings of this research was that the marginal savings don't increase with income in the long run as Keynes had predicted, but remain constant.

Kuznets work was published in 1941 in two volumes by NBER and was titled 'National Income and Its Composition', 1919-1938. This work, which was co-authored with Lillian Epstein and Elizabeth Jenks, introduced the concept of national income, ways to measure national income and the distribution of national income by industrial source, income and final product. The second volume was a detailed compilation of the basic data of various sectors of the economy. He later published another book titled, 'National Income: A Summary of Findings' in 1946, which was also published by NBER.

During his career, Kuznets measures of GNP were considered far more reliable than earlier estimates. Over the course of many decades, he also calculated GNP with the historic data, computing national income back to 1869. Let us not forget that before Kuznets came on the scene, the business and economic data released by the Department of Commerce (DOC) Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce (BFDC) was unreliable and incomplete. By the Great Depression, the lack of data on the nation's production and income became evident. Only after NBER put Kuznets in charge of a study using new methods for generating national income estimates in 1930, did the data reliability improve. This also led to his aforementioned publication 'National Income'.

His approach to the computation of national income took forward the work on econometrics begun by Tinbergen and Frisch, who had received the Nobel Prize in 1969. Kuznets work energised quantitative economics, and he is credited with helping form modern economics and econometrics. His work on the detailed calculation of GNP is also credited with fuelling the Keynesian revolution since Keynes ideas on the role of government expenditure and the consumption function could now be tested more fully and easily.

In fact, with his detailed data, it was Kuznets himself who empirically examined the absolute income hypothesis of Keynes (1936). We may recall that in his 'General Theory', Keynes had hypothesised a positive relationship between income and consumption. As disposable income rises, real consumption (i.e., consumption adjusted for inflation) will also rise, but not at the same rate. Keynes basically introduced the consumption function and hypothesised that the marginal propensity of consumption would also be less than one (marginal propensity to consume is basically the amount of incremental income that will be consumed). Kuznets found that Keynes' hypothesis though accurate in short-run cross-sections, broke down in the long run. This difference in the consumption function between the short run and long run was later explained by Modigliani's life-cycle income hypothesis and Milton Friedman's permanent income hypothesis. We may recall that Modigliani suggested that income varies over people's lives and people move their savings from times when income is high to when it is low. Friedman's permanent income hypothesis, on the other hand, suggested that people experience random and temporary changes in income from year to year. A person's income consists of two components: permanent and transitory income, and consumption is a function of permanent income, not total income as in the Keynesian model. This explains the difference between the short and long-run consumption function.

b. Economic growth & income distribution

After working on national income, Kuznets moved into a new research area in the late 1930s, after the War. This was to study the relationship between changes in income and growth. He suggested that there four key elements of economic growth. The elements were demographic growth, growth of knowledge, in-country adaptation to growth factors, and external economic relations between the countries. Kuznets embarked on an empirical study of these four elements. According to him, the general theory of economic growth should explain the development of advanced industrial countries, and the reasons that prevent the development of backward countries.

He collected and analysed statistical indicators of the economic performance of 14 countries in Europe, the US and Japan for 60 years. Based on this data, tested a number of hypotheses relating to various aspects of the mechanism of economic growth, the level and variability of growth, the structure of the GNP and distribution of income between households and the structure of foreign trade. Kuznets found that GNP growth is accompanied by a transformation of the economic structure, which includes a change in the structure of production, occupational patterns, income distribution and spatial distribution of the population. Along with these changes, governmental regulation also evolves. In his opinion, such changes are essential for the overall growth and, once started, shape, constrain or support the subsequent economic development of the country.

His major thesis was the development experience of today's developing countries was very different from that of developed countries. In other words, there is no single growth process where all countries went through the same 'linear stages' in their history. This thesis effectively was the beginning of the separate field of development economics.

His other major work was captured in the book Modern Economic Growth. In his Nobel lecture, he defined economic growth as follows:

"A country's economic growth may be defined as a long-term rise in capacity to supply increasingly diverse economic goods to its population, this growing capacity based on advancing technology and the institutional and ideological adjustments that it demands."

From the above definition of economic growth, it is clear that it has three basic components: long term rise in capacity to supply, technology and institutional and ideological adjustments. Kuznets further identified six characteristics of economic growth:

Growth in per capita output and population

Rate of rise in productivity of inputs

High rate of structural transformation of the economy

Change in society and ideology

Spread of technological change from developed countries to the rest of the world

Limitations in the spread of economic growth to developing countries

c. Kuznets curve

Kuznets' other important contribution is the inverted U-shaped relation between income inequality and economic growth. Based on the patterns of income inequality in developed and underdeveloped countries, he proposed that as countries experienced economic growth, the income inequality first increases and then decreases. Initially, countries had to shift from agricultural to industrial sectors in their growth path. He thought economic inequality would increase as rural labour migrated to the cities, keeping wages down as workers competed for jobs. But according to Kuznets, social mobility increases again once a certain level of income was reached in 'modern' industrialised economies, as the welfare state takes hold and people get more educated.

There is, however, mixed empirical support for Kuznets' inverted U-curve. On one hand, many advanced countries have followed this hypothesis. But in Netherlands and Norway and in the East Asian economies of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, income inequality mostly declined with economic growth.

A modification of the Kuznets curve has become popular to chart the rise and subsequent decline in pollution levels of developing economies, which is also called the environmental Kuznets curve. First developed by Gene Grossman

and Alan Krueger in 1995 and later popularised by the World Bank, the environmental Kuznets curve follows the same basic pattern as the original Kuznets curve. Again, the empirical support for the environmental Kuznets curve is mixed.

Kuznets and public policy

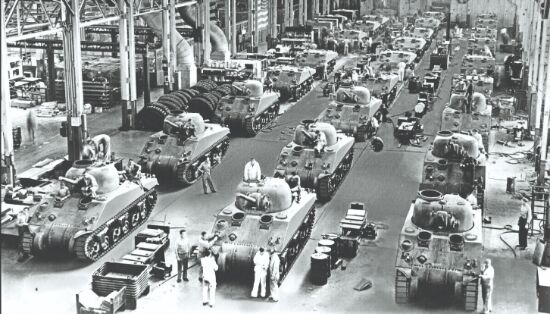

After migrating from the then USSR, Kuznets worked in a number of public offices. Beginning with the NBER, where he worked as a researcher in 1931, Kuznets was again detailed to the Federal Government after the War at the War Production Board. Kuznets was associate director of the Bureau of Planning and Statistics, an arm of the War Production Board. There he assessed the nation's capacity to expand military

production and the implications for the economy as a whole. His expertise in national accounting was vital to these assessments. After World War II, Kuznets also took on the role of advisor to many Asian governments on their national income accounts.

Kuznets was also active in academia since the time of his working in NBER. From 1931 until 1936, Kuznets was a part-time professor at the University of Pennsylvania and as professor of economics and statistics from 1936 until 1954. In 1954, Kuznets moved to Johns Hopkins University, where he was a professor of political economy until 1960. From 1960 until his retirement in 1971, Kuznets taught at Harvard University.

His contribution to public policy is indisputable. His methods of computing national income are followed the world over even today. But it is his work on economic growth and income distribution that has informed public policy in countries across the world. The Kuznets inverted U-curve, in particular, has influenced policy on economic growth and the changes in income distribution it brings about. According to Kuznets, economic growth is accompanied by structural changes such as changes in shares of outputs and inputs, change in employment and labour productivity.

His work, 'Modern Economic Growth' continues to be relevant for development policy, particularly in developing countries. The following questions that he raised in his Nobel lecture are still pertinent for those in charge of public policy across the world:

"Does the acceleration in the growth of product and productivity in many developed countries in the last two decades reflect a major change in the potential provided by science-oriented technology, or a major change in the capacity of societies to catch up with that potential? Is it a way of recouping the loss in standing, relative to such a leader as the United States, that was incurred during the depression of the thirties and World War II? Or, finally, is it merely a reflection of the temporarily favourable climate of the U.S. international policies? Is the expansion into space a continuation of the old trend of reaching out by the developed countries, or is it a precursor of a new economic epoch?"

Conclusion

Kuznets passed away in July 1985, but his rich legacy endures. His work on the computation of national income, the inverted U-curve relationship between income inequality and economic growth and modern economic growth still informs policy planners across the world, particularly in developing countries. There certainly have been competing theories for the relation between growth and inequality. For example, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson theorised that the inequality due to capitalist industrialisation contained "seeds of its own destruction" and give way to political and labour reform in countries like Britain and France, enabling redistribution of wealth. Again, in East Asian economies land reforms paved the way for equitable redistribution even though political reform was delayed. In other words, it was politics, and not economics as Kuznets suggested, that determined inequality levels. That said, Kuznets' model provides a good reference point on any work on economic growth.

The writer is an IAS officer, working as Principal Resident Commissioner, Government of West Bengal. Views expressed are personal