The Nobel Series: Decoding financial markets

Franco Modigliani, a Neo-Keynesian economist, played a major role in establishing the ‘life-cycle hypothesis’ which explains the level of savings in the economy, and the ‘Modigliani-Miller theorem’ that establishes the independence of a firm’s value from capital structure

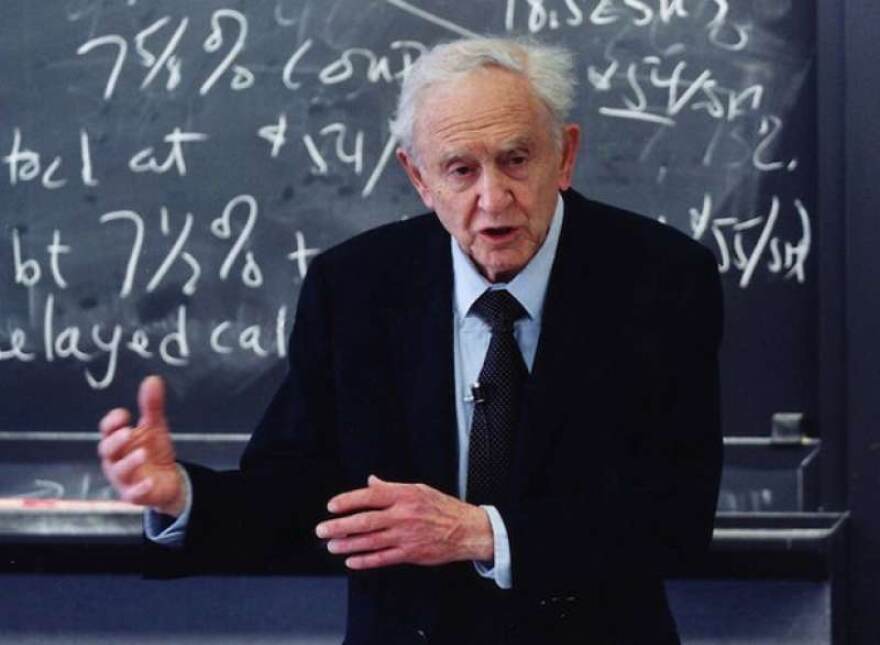

The Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1985 was awarded to Franco Modigliani, who was at MIT, USA at the time. He was given the prize for his original contributions in understanding how the financial markets work.

Modigliani was not initially an economist and had enrolled as a law student in the Sapienza University of Rome. His initial works included several essays for the fascist magazine "The State", in which he argued for a socialist economy. His arguments were largely similar to the ones proposed by Oskar Lange and Abba Lerner. He left for Paris in 1938 when he was disillusioned by the Fascist regime,

and from there, he migrated to the US in 1939. In the US, he joined the New School from where he did his PhD in economics under the supervision of Jacob Marschak and Abba Lerner in 1944. He first taught at Columbia University from 1942-44 and then at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. From 1952 to 1962, he was a faculty at the Carnegie Mellon University, and in 1962 he joined MIT, from where he retired.

Modigliani had several original works to his credit. The life cycle hypothesis, the Modigliani-Miller theorem and the theory of rational expectations were some of these works. In this article, we will review the works of Modigliani and see how they are relevant for public policy even today.

Main works of Modigliani

Modigliani's best-known work is the life cycle hypothesis proposed by him. The life cycle hypothesis explains the level of savings in the economy. It may be recalled that Milton Friedman had proposed the permanent income hypothesis wherein a person's income has two parts: permanent and transitory. According to Friedman, permanent income is the long term average income expected by an individual and transitory income is a windfall or temporary income. It is primarily the permanent income that determines the level of savings and consumption. Friedman was proposing his hypothesis in contrast to the Keynesian theory of declining marginal propensity to consume. In Keynes' words, "households increase their consumption as their income increases, but not as much as their income increases". According to Friedman, Keynes was referring to total income and not permanent income. Even before Friedman, Kuznets had questioned Keynes' theory of declining marginal propensity to consume. It may be recalled that in 1942, Kuznets found that in the US, the long-term saving: income ratio had not increased over time. In 1957, Friedman was essentially addressing the contradiction in Keynes' theory pointed out by Kuznets.

Modigliani, like Friedman, was also trying to address the Keynes-Kuznets contradiction. However, while Friedman proposed that people save through their life for themselves and their children, Modigliani proposed that people saved only for themselves. The difference was the length of the planning period: for Friedman, this period is infinite, and for Modigliani, it is finite.

Hence, according to Modigliani, people aspire for a stable level of consumption all through their lives. Modigliani argued that people save in high-income years and spend more than their income in low-income years. Accordingly, income is low for those beginning their working lives, increases in the middle years and then declines again on retirement. Therefore, young people borrow to spend more than their income, middle-aged people save a lot, and old people run down their savings.

The other major work of Modigliani was the Modigliani-Miller theorem, which he proposed in 1958 when he was at Carnegie Mellon University. The theorem simply says that the value of a firm is independent of the source of finance, i.e. it is independent of whether the financing is by equity or debt, given that the financial markets function perfectly and there are no transaction costs. In other words, the debt-equity ratio is of no consequence for firms. The following quote from the website of the Nobel Prize elaborates the concept further:

Modigliani and Miller define the value of a firm as the sum of the market value of the equity stock and the market value of its debts. Their theorem states that this value is equal to the discounted value of the flow of its expected future returns, before interest, provided that the return on investment in shares of firms in the same risk class is used as the discount factor. This implies that the value is completely determined by this discount factor and by the return on existing assets, and is independent of how these assets have been financed. It further implies that average capital cost is independent of the volume and structure of the debts and equal to the expected return on investment in shares of firms in the same risk class.

Modigliani and Miller further developed this theorem and extended it to dividends. They proposed that the value of a firm is also independent of its dividend policy: while an increase in dividend raises the income of the shareholder, it also reduces the share value.

Modigliani's other contribution included his work on rational expectations. In a paper co-authored with Emile Grunberg in 1954, he argued that people adjust their economic behaviour based on the impact they expect government policy to have on them. While this began the rational expectations theory, Modigliani did not approve of the extremes to which it was taken. Interestingly, Modigliani laid the foundation for the rational expectations school, which, in turn, was used to criticise the effectiveness of the Keynesian macroeconomic policy. Ironically, Modigliani was an ardent Keynesian all his life.

Modigliani also worked on monetary policy and how it should be used in setting the targets for output and unemployment. In a 1975 paper, he suggested an unemployment rate of 5.5 per cent and called it the non-inflationary rate of unemployment (NIRU) that monetary policymakers should target. According to him, this was an improvement over the concept of natural rate of unemployment, which was initially proposed by Friedman. We may recall that the natural rate of unemployment represents the lowest unemployment rate where inflation is stable. Of course, there is still no agreement among economists or bankers on what this natural rate ought to be.

Application in public policy

The life cycle hypothesis tells us that saving and consumption are not a function of income alone, but also of wealth. The motivation for the life cycle hypothesis was of course the diminishing marginal utility of money: if income is high during working life, the marginal utility of spending extra money falls. And that it is difficult to earn in the early days and old age.

The life cycle hypothesis has inspired many public policy actions. One of these is the idea that the introduction of pension systems leads to a fall in savings. A comparison of different countries with varying demographic features would lead to different consumption and savings behaviour and therefore different pension systems. As the Nobel website tells us:

The life cycle hypothesis has been used as a theoretical basis for many empirical investigations. In particular, it has proved an ideal tool for analyses of the effects of different pension systems. Most of these analyses have indicated that the introduction of a general pension system leads to a decline in private savings, a conclusion in full agreement with the Modigliani-Brumberg hypothesis.

The Modigliani-Miller theorem has also been applied in understanding the investment decisions of the firms. It may be recalled that the theorem was based on the assumption of the existence of efficient capital markets, frictionless markets and the absence of taxes. This leads us to the following aspects of investment decisions:

Investment decisions can be separated from the corresponding financial decision.

The maximization of the market value of the firm is most important for making an investment decision.

Capital cost refers to total cost and should be measured as the rate of return on capital invested in shares of firms in the same risk class.

The Modigliani-Miller theorem gave a new insight into the world of corporate finance. After winning the Nobel Prize, Modigliani had used a pizza slice analogy to illustrate his point dramatically: the size of the pizza is independent of the number of slices you cut from it. In other words, the changing of the capital structure (debt-equity ratio) doesn't affect the firm's cash flow and hence does not affect the overall value of the firm.

At first, corporate finance experts ignored the theorem since the assumptions were too unrealistic but academic economists found the theory to be true. The theorem was found to have great value in course of time and led to new research in many directions. The theorem was also applied in a wide array of corporate finance areas. For example, given the assumptions of the theorem, many corporate actions, including leverage, have no impact on firm value. Indeed, the assumptions imply that the value of a firm is determined solely by the firm's investments or assets (the left side of the balance sheet), not how those investments are financed (the right side of the balance sheet). The assumptions also imply that hedging activities, leasing versus owning, the form of legal organization, the compensation structure, the state of incorporation and the legal rules that follow etc. have no impact on firm value either. The theorems however leave a big hole: are there any situations where capital structure can affect the value of the firm? Modigliani and Miller themselves returned to this question in 1988 and suggested that capital structure can indeed affect the value of the firm if the assumptions are relaxed. In a result widely called the reverse Modigliani-Miller theorem, they held that capital structure becomes important for the value of the firm in a world of taxes and positive transaction costs.

Conclusion

We saw above that the life cycle hypothesis, as well as the Modigliani-Miller theorem, had a significant impact on the way economists and corporate finance experts understood savings and consumption and the capital structure.

However, both had their share of critics.

The life cycle hypothesis was criticised on grounds of unrealistic assumptions. For example, it assumes people run down wealth in old age, but often this doesn't happen as people would like to pass on inherited wealth to children. Also, there can be an attachment to wealth and an unwillingness to run it down. It also assumes rationality. But prospect theory and behaviour economics tell us that there may be other motivations apart from rationality. Another criticism is that rather than smoothing out consumption, individuals may prefer to smooth out leisure: working fewer hours during working age, and continuing to work part-time in retirement. There were similar criticisms of the Modigliani-Miller theorem as we saw in the discussion above.

Notwithstanding the critiques, Modigliani's contributions, primarily the life cycle hypothesis and the theorem continues to spark research in other areas as well as guide policymaking in areas such as designing pension systems, corporate finance, banking etc. The latter has gained even more relevance in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis which has seen recurring challenges to the banking sector that have been occurring all over the world ever since.

The writer is an IAS officer, working as Principal Resident Commissioner, Government of West Bengal. Views expressed are personal