New Institutional Economics: Resolving collective action dilemmas

With the failure of the neoclassical model in addressing the supply of public goods and common-pool resources, NIE offers the necessary tools to address the problems arising out of collective action dilemmas

We continue to develop the building blocks of NIE+ after having covered transaction costs, property rights and asymmetric information in the last few articles. In this article, we will turn our attention to public goods and CPRs and their supply. More specifically, we will see the challenges that arise in the supply of public goods and CPRs, something that has been referred to as 'collection action dilemmas/problems'.

Nature of public goods

In general terms, public goods are those that are consumed by the public at large and supplied by the government from taxpayers' money. Recall that in the neoclassical model, the good is identical, exchange is costless and the transaction is instantaneous and markets clear when supply equals demand. This nice scheme of things breaks down in the case of public goods because of the characteristics of such goods. One has to turn to New Institutional Economics to find answers to questions of public goods and common-pool resources (CPR). Let us see how.

The theory of public goods was postulated by Paul Samuelson in 1954. It applies to goods which are consumed collectively or jointly. According to this theory, public goods have two characteristics: a) non-excludability, i.e., once a good is provided, the benefits flowing from it can't be stopped for anyone and b) non-rivalry in consumption, i.e., one person's consumption does not reduce the quantity available for others. Some common examples of public goods are the police, national defence, recreation parks, basic television, and radio etc. After Samuelson, the work on public goods was taken forward by NIE economists such as Ronald Coase and Mancur Olson. For example, Coase gave the famous example of the provision of a lighthouse as a public good. Since it is difficult to exclude ships from using its services, a lighthouse's services are non-excludable. Any ship's use does not reduce the use of the lighthouse by other ships and hence it is non-rivalrous. But since most of the benefit of a lighthouse accrues to ships using particular ports, lighthouse maintenance can be profitably bundled with port fees (Ronald Coase, 'The Lighthouse in Economics', 1974). This has been sufficient to fund actual lighthouses and overcome the undersupply problem typical of public goods.

The opposite of a public good is a private good, which is both excludable and rivalrous. These goods can only be used by one person at a time–for example, a cupcake or a coke can. Private goods generally cost money, which pays for their private use. Many of the goods and services that we consume in our everyday lives and are paid for by us are private goods. Although they are not subject to the free-rider problem, they are also not available to everyone, since not everyone can afford to purchase them.

In some cases, goods have some characteristics of a public good and are referred to as quasi-public goods. For example, the post office or a toll highway can be seen as a public good, since it is used by a large portion of the population and is financed by taxpayers. However, unlike a pure public good like the air we breathe, using the post office or a toll highway requires some costs, such as paying for postage and paying the toll. Further, although these goods are made available to all, their value can diminish as more people use them. For example, a city's road system may be available to all its residents, but the value of the roads declines when they become congested during rush hour.

Another type of good is common pool resource. Such a good is rivalrous but non-excludable. Such goods raise similar issues to public goods: the mirror to the public goods problem for this case is the 'tragedy of the commons'. It was the Nobel Prize winner of 2009, Elinor Ostrom, who proposed this additional modification to add common pool resources to the typology. She replaced rivalry of consumption with 'subtractability' of use. She suggested that common-pool resources shared the attribute of 'subtractability' with private goods and non-excludability with public goods. An example of a common-pool resource is open access grazing fields. It is so difficult to prevent everyone's cattle from grazing in the open fields that such fields can be seen as a non-excludable resource, but obviously, the open fields are not a limitless resource and one person's cattle will reduce the grass available for the others' cattle.

Finally, there are club goods, which are excludable but are non-rivalrous such as amusement parks which charge a ticket. Once a ticket to the park is purchased, one person's consumption can't reduce the consumption of the other person.

The following table summarizes the typology of goods discussed above:

Public goods, CPR & market failure

We have seen above that in the neoclassical model, the goods in the market are identical, the exchange is costless and the transaction is instantaneous. It is easy to see that it is difficult to accommodate public goods and CPRs in the neoclassical model. In fact, the market fails when it encounters public goods and CPRs. As we know, market failure occurs when the price mechanism fails to account for all of the costs and benefits necessary to provide and consume a good. In the case of public goods, this happens because of the 'free-rider' problem. The 'free rider' problem arises in the supply of public goods because people don't pay for the good being supplied or don't pay enough. This leads the market to fail or undersupply the good. In economic terms, efficient equilibrium will no longer be where the individual marginal rate of substitution=price ratio=marginal rate of transformation or marginal willingness to pay=price=marginal costs.

The free-rider problem can also be expressed in terms of a prisoners' dilemma game. Say that two people are thinking about contributing to a public good such as a public park. While the best solution for the society is that both should contribute and 'supply' the park, this does not happen because private benefit diverges from social benefit. Each of them is tempted to free ride and not contribute as a result of which the park is not 'supplied' at all. There are a lot of ways to get around this free-rider problem whereby the government has to step in. Let us see how.

Role of government

If public goods have to be supplied, one has to find a way of assuring that everyone will make a contribution and prevent free riders. This can happen by government ensuring that people pay taxes and make group decisions about the supply of public goods.

In some cases, markets can also produce public goods if the government provides the right incentives to do so. For example, the government in many countries has provided an incentive structure that allows private players to provide radio services. Radio services are nonexcludable and nonrivalrous.

In other cases, social pressures and personal appeals can be used, rather than the force of law, to reduce the number of free riders and to collect resources for the public good. For example, neighbours sometimes form an association to carry out beautification projects or to patrol their area after dark to discourage crime.

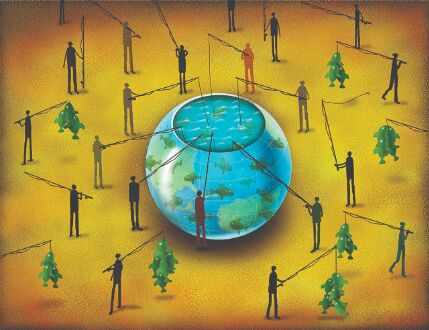

The above arguments for the role of the government in supplying public goods apply to CPRs as well. We saw that goods that are nonexcludable and rivalrous are called 'common-pool resources'. A typical problem in CPRs such as forests and fisheries is that they tend to be overharvested and lead to the tragedy of the commons as Garett Hardin had predicted in 1968. The CPR can also be seen as a prisoners' dilemma game in the same way that the supply of a public good as seen above. In the case of CPRs, the government can resort to other measures to overcome the free-rider problem some of which are: a) Set quotas, for example, quotas on how much fish a vessel can catch, but this is difficult to implement and monitor; b) Bring legislation, for example on the size of the vessel or the size of the net and; c) Provide compensation to move away from fishing to alternative economic activities.

Collective action issues

We saw above that the issues related to collective action grew out of the problem of the supply of public goods initially discussed by Samuelson (1954). We also saw that the free-rider problem detracts from the supply of public goods. This is also referred to as a collective action dilemma since people can't take collective action and decide on how to contribute to providing the public good.

The theory of collective action was developed by Olson (1965) wherein he demonstrated that large groups would have a problem in supplying a collective good because of the free-rider problem. The nature of the collective good being non-excludable, it would be difficult to prevent all members of the group from enjoying the benefit of the good.

Further, collective goods are also characterised by jointness in supply. The free-rider problem dominates and leads to a failure on the part of the group to supply the good.

Olson's work continues to be the reference for most research on collective action. Nevertheless, some of the shortcomings of Olson's analysis are: first, all public goods problems don't involve a collective action problem and all collective action problems don't involve public goods; second, it seems that Olson was specifying two dimensions to a group: size (small, intermediate and large) and nature (active and latent) and there was a conflation of the two dimensions in his discussion; three, Olson overlooked asymmetries in a group and the resultant hurdles they may cause in overcoming collective action problems (Hardin 1982); fourth, it seems odd that a group should exist only if its members are given selective incentives and not for the main purpose of supplying the collective good itself, and finally, the size of a group need not be an obstacle to collective action.

Olson's ideas have been extended to extensive research in the area of common-pool resources. In particular, Ostrom (1990) and Oakerson (1992) using Olson's theory in conjunction with prisoners' dilemma and Hardin's tragedy of the commons have made a strong case for local institutions in overcoming collective action dilemmas and managing common-pool resources such as fisheries, forests and irrigation. Ostrom has emphasised the role of trust, norms and social capital in overcoming such problems.

Conclusion

We have discussed above that the neoclassical model doesn't work in the case of public goods and CPRs and one has to turn to NIE for answers. In fact, one is faced with market failure when one is confronted with the supply of public goods and CPRs. This is because of the free-rider problem, which is also referred to as the collective action problem. This problem basically arises when everyone does not pay for the good but wants to ride 'piggyback' for free resulting in the non-supply of the good by the market. The collective action dilemma for the group is how to ensure that everyone pays up. Since the market can't ensure this, the government has to step in through taxes and incentives to ensure the supply of the public good. Alternatively, the community can take it upon itself to frame rules for the use of CPRs such as forest and fisheries and ensure that the 'tragedy of the commons' doesn't occur.

The above discussion has clear implications for public policy in critical areas such as infrastructure (highways, ports, power, all of which have public good characteristics) and climate change (forest, fisheries and other CPRs and public goods such as air and water). The right incentive structure and institutions will go a long way in guiding us to the desired goal of sustainable development.