First-Five Year Plan: Buttressing primary pillars

Although the first Five-Year Plan well surpassed the goals it had set for agriculture and irrigation in the public sector, it left urban planning and industrialisation at the mercy of the ‘dependent’ private sector

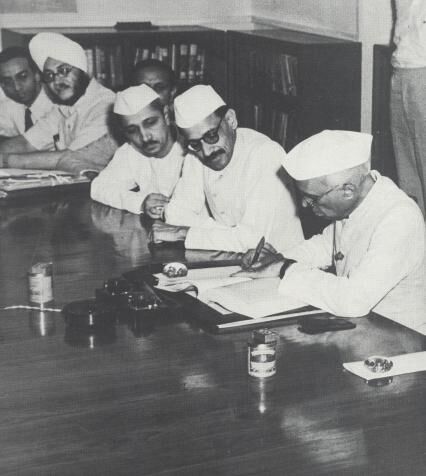

The first Five-Year Plan was launched in 1951. On July 9 that year, the plan was presented to the Parliament by India's first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. As we know, the Planning Commission was set up in March 1950, and the first task before the Commission was to put together a development plan which would lead to balanced economic growth and address the problems of poverty and unemployment.

We may recall that the first plan was prepared in the backdrop of the Partition and the country was struggling with the influx of refugees, food shortage and high levels of inflation. It therefore focused primarily on the development of the primary sector, specifically agriculture and irrigation.

In this article, we will focus on the key aspects of the first Five-Year Plan, its achievements and what it could have done better.

Key features

Before the preparation of the first plan, the Planning Commission had the experience of framing a six-year plan of economic development for the country, which was to be placed before the Commonwealth Consultative Committee. This plan was later incorporated into the Colombo Plan — a regional plan for South and South-East Asia.

The first plan, which comprised 39 chapters, was limited to the public sector. Growth of the private sector was restricted only to the developments that followed from the public sector. To quote from the draft outline of the first Five-Year Plan:

The scope of our planning is limited, in the first instance, to the public sector and to such developments in the private sector that follow directly from the investments in the public sector, or, on the whole, are amenable to planning and control. With the data available, we have tried to view as far as possible the repercussions of the plans for these sectors on other sectors of the economy and on the development of the system as a whole, but it must be emphasised that the scope for precision in this respect is. at this stage of our work, strictly limited.

From the sectoral perspective, the first Five-Year Plan was equally concerned with the development of agriculture and industry as well as with providing affordable healthcare and education to all. While agriculture and related sectors such as irrigation (along with power and transport) were to be developed by the public sector, industry was to develop through private resources and initiatives. In addition, the challenges arising out of the Partition and the Second World War also led to a focus on rehabilitation and community development.

The emphasis in the first plan was on savings and capital formation. This was because higher savings were a necessary condition for higher capital formation which, in turn, was a precondition for high economic growth. To quote from Chapter 1 of the first plan document:

These are aspects of the problem of economic development which have to be constantly kept in view. Given these basic conditions of rapid and sustained progress, institutional as well as others, the key to higher productivity and expanding levels of income and employment lies really in stepping up the rate of capital formation. The level of production and the material well-being a community can attain depends, in the main, on the stock of capital at its disposal, i.e., on the amount of land per capita and of productive equipment in the shape of machinery, buildings, tools and implements, factories, locomotives, engines, irrigation facilities, power installations and communications. The larger the stock of capital, the greater tends to be the productivity of labour and therefore the volume of commodities and services that can be turned out with the same effort. The productivity of the economy depends on other things also, as for instance the technical efficiency and attitude to work of the labour that handles the available capital equipment. But the stock of capital reflects in a concrete form the technological knowledge that underlies the organised processes of production, and while other factors are important and essential a rapid increase in productivity is conditional upon additions to and improvements in the technological framework implicit in a high rate of capital formation.

Citing the experience of developed countries such as the USA, the UK and Japan, the plan suggested that capital formation would have to rise to about 20 per cent of national income, from the low levels of five per cent that prevailed at the time. For capital formation to rise to such a high level, resources would be needed, which, in turn, can come from a higher level of savings.

It is interesting to note that the first Five-Year Plan also outlined the need for a longer perspective plan, spread over 25-30 years, and the importance of long-term targets and objectives, including the need for institutional development. To quote from the Plan document:

It is necessary to visualise the problem of development over a period of twenty-five or thirty years and to view the immediate five year period in this broader context. In formulating a plan of development for a particular period, an estimate of what is feasible must, no doubt, carry more weight than abstract reasoning as to a desirable rate of growth. But, there is clearly a need for looking beyond immediate possibilities and for taking a view of the problem even from the beginning in terms of continuing and over-all requirements, and for preparing the ground in advance. Precisely for the reason that the development of a country is a somewhat long-term process, the institutional and other factors which affect it can be changed to the desired extent and in the desired direction through conscious effort. Moreover, a programme of development even for the short period would fail to have direction and perspective unless it is in some way linked to certain long-term targets and objectives relating to the kind of economy and social framework which it is proposed to evolve. In other words, while it is important to preserve throughout a pragmatic and non-doctrinaire approach, and also to bear in mind the limitations involved in any calculation of long-term development possibilities, it is of the essence of planning that it must have a wider time-horizon than immediate requirements and circumstances might seem to indicate.

The first plan was drafted by the noted economist KN Raj, and was inspired by the well-known Harrod-Domar model. We may recall that the Harrod-Domar model was a set of equations, wherein growth was a function of an increase in capital formation which, in turn, was dependent on raised savings. The model also underlined the importance of the incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR) — a low ratio would mean efficient investment and a higher growth rate. For the first plan, an ICOR of 3 was assumed for the growth projections. In other words, an increase in one unit of national income would need three units of capital stock.

Financial outlays

The financial outlay for the first plan was initially Rs 2,069 crores and was later revised to Rs 2,378 crores. This outlay was distributed across seven broad areas: irrigation and energy (27.2 per cent), agriculture and community development (17.4 per cent), transport and communications (24 per cent), industry (8.6 per cent), social services (16.6 per cent), rehabilitation of landless farmers (4.1 per cent) and others (2.5 per cent).

The incurred expenditure actually amounted to Rs 1,960 crores, of which the investment component was of the order of Rs 1,560 crores. In addition, the private sector investments amounted to Rs 1,800 crores. Thus, the total investment in the private and public sectors together amounted to Rs 3,360 crores. Of the actual expenditure of Rs 1,960 crores in the public sector, Rs 601 crores (31 per cent) went to agriculture including community projects and irrigation; Rs 523 crores (27 per cent) to transport and communications; Rs 459 crores (23 per cent) to social services; Rs 260 crores (13 per cent) to power and only Rs 117 crores (6 per cent) to industry including village and small industries.

The first plan was financed with budgetary sources (73 per cent), deficit-financing (17 per cent) and external funding (10 per cent).

The target growth rate was 2.1 per cent and the national income was expected to rise from Rs 9,000 crores to Rs 10,000 crores by the end of the plan (a rise of 11 per cent). Further, the first plan projected that the national income would rise from Rs 9,000 crores in 1951 — by about 160 per cent in 22 years, and per capita income would double in the same period if capital formation is increased by 2/3rd of income every year, but per capita consumption would fall as per this projection. Consequently, the authors settled for a rise in capital formation between 1/4th to 2/3rd of national income, so that there was no sharp cut in per capita consumption expenditure.

An appraisal

As it turned out, the growth rate achieved was 3.6 per cent against the target of 2.1 per cent and national income went up by 18 per cent (as opposed to the target of 11 per cent). The rate of investment also rose by five per cent of national income to 7.3 per cent by the end of the plan period. A good monsoon also led to better than targeted agricultural production and high crop yields, with agricultural production rising by 17 per cent. The irrigated area also increased by 31 per cent and the community development project took off. Industrial production rose by 39 per cent, but most of this rise took place in small and medium industries. In addition, the zamindari system was abolished and the tenancy reforms began taking shape.

Further, at the end of the plan, five IITs began to function, UGC was set-up and the groundwork for the second five-year plan was laid. Also, the large outlay on irrigation led to major projects such as Bhakra-Nangal, Hirakud and Damodar Valley taking off. Many public sector industrial units such as Sindri Fertilisers, Chittaranjan Locomotives and the integral coach factory made progress.

However, while the progress was admirable, the biggest lacunae was insufficient public expenditure on industry. Not only that, there was no mention of setting up large and capital goods industries. Another shortcoming was the absence of a vision on infrastructure development such as railways, shipping, ports, highways and power, with most of the outlay allocated to irrigation. There could have been some initiative to raise finances for infrastructure development, including exploring external borrowings. There was also no discussion on the impending urban challenges or the need to build new cities.

Even in the areas where the plan was more successful, the progress was, in fact, rather modest. For example, the proportion of irrigated area to net sown area in 1955-56 worked out to no more than 22 per cent as compared with 19 per cent in 1948-49, and only about 0.9 per cent villages were electrified as against 0.5 per cent before the Plan. In other words, the heavy reliance on monsoons continued and the penetration of power was limited. In primary education, a large proportion of children remained out of school.

Unemployment actually worsened during the course of the Plan when the outlay had to be stepped up. As against the addition of 10 million people to the labour force, the Plan claimed to have found employment for only 4.5 million persons, which meant that investment was not sufficient.

Moreover, as Vakil and Brahmanand have pointed out, "the organisational mechanism of the government was so rigid as to be incapable of effectively and adequately utilizing the 'windfall factors' with which nature favoured the Indian economy. The food surpluses of 1953 and 1954, instead of being utilised for investment, were either frittered away in the form of a rise in the consumption standards or simply wasted".

The first plan did see an increase in agricultural production, an improvement in the balance of payments and a decline in prices, but this was largely on account of factors outside the plan. This led Professor Gadgil to remark that "the major achievements of the First Five Year Plan period may perhaps be said not to have been planned at all."

Conclusion

While the first Five-Year Plan did achieve its growth targets, there was much that remained to be done. Many of the areas such as large infrastructure development, urban development and industrial development were either not discussed or covered cursorily. However, it did give confidence to the planners to aim for bigger goals and the stage was set for the second five-year plan.

The writer is an IAS officer, working as Principal Resident Commissioner, Government of West Bengal. Views expressed are personal