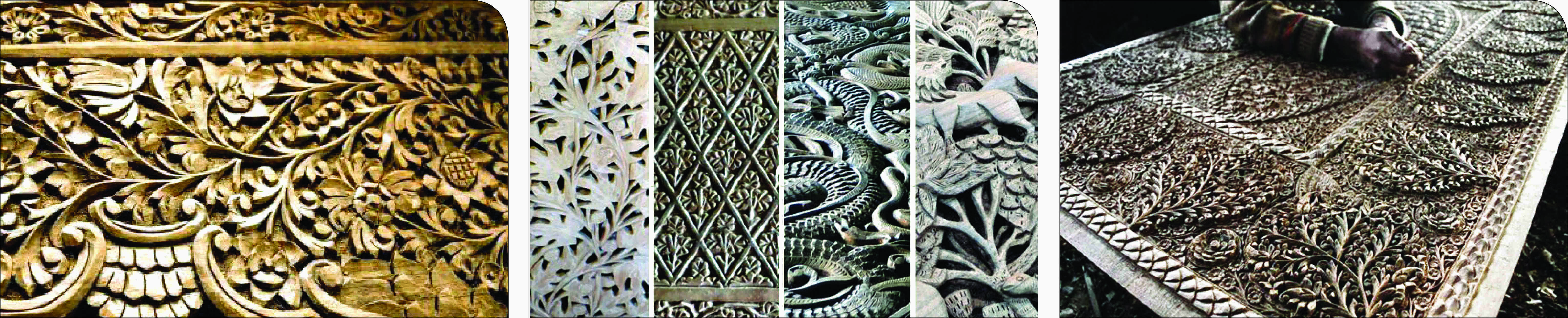

Exquisite carvings of Kashmir

While the demand for Kashmiri walnut carving is on the rise, the expert 'karigars' who create it in 'karkhanas' are finding it hard to preserve their craft which remains under-rewarded

Although wood carving is one of the oldest forms of art — tracing its antecedents to the Stone Age, the walnut carving of Kashmir with its distinct style and pattern is perhaps the most famous of all. Nikita Kaul traces the walnut wood carving tradition in Kashmir to the Persian saint Sheikh Hamza Makhdoom. After his visit to Kashmir during the reign of Zain-ul-Abadin in the 15th century, Sheikh Saheb invited 700 of Persia's best craftsmen to the valley to teach this art to the people of this beautiful vale which was also the natural home to Juglans Regia (walnut) tree that grows widely in Kashmir region at an altitude of 5,500–7,500 feet above mean sea level (AMSL). This wood is hard and durable, and its close grain and texture facilitate fine and detailed work.

Initially restricted to the creation of elaborate palaces such as Zain-ul-Abadin's great Razdani palace and mausoleums like the shrines of Noor-ud-din-Wail at Charar-e-Sharif, the Naqshaband Mosque and the shrine of Nund Rishi, the art, over time, found expression in geometric designs of wood panels for ceilings, arches and doorways called Khatamband. Several other products such as toys, bowls, platters, jewellery boxes, wall plaques and table lamps, bedsteads and larger items of furniture also found a market, not just within Kashmir, but throughout the country and abroad. In fact, walnut carving was one of the first products from the state to apply for, and get, the GI tag way back in 2012. The GI is held by TAHAFUZ — a society registered under the J&K Societies Registration Act.

Walnut trees are of four varieties — 'Want', 'Dunu', 'Kakazi' or 'Burzol' (which are cultivated) and 'Khana' (which is found in the wild). The preferred raw material for the fine woodcarving of Kashmir comes from 'Dune' which is cut only when it matures to an age of 300 years. The wood derived from the root is almost black, with the grain more pronounced than the wood from the trunk, which is lighter in colour. The value of the wood differs, with the wood from the root being most expensive. Branches have the lightest colour with no noticeable grain. It is the dark part of wood which is best for carving, as it is strong.

The actual production of these intricate carvings with recurrent motifs of rose, lotus, iris, bunches of grapes, pears and chinar leaves — besides patterns taken from Kani and embroidered shawls — takes place in in karkhanas (workshop) in downtown Srinagar. As Kaul writes: "Within the labyrinth of the downtown by lanes are sporadically situated karkhanas. A karkhana is headed by an ustad (master) who is knowledgeable about craft and owns the means of production. Those who work in a karkhana alongside the ustad are karigars (skilled labourers), who earn wages for their work. The craftsmanship of walnut wood carving includes three sub-categories of craftwork — joinery (or carpentry), carving and polishing. Hence, a karkhana requires these three skills, and each karigar holds expertise in either of them." Traditionally, the karkhanas were strict 'male preserves' but, with men finding alternate livelihood options more attractive, and the J&K government's handicrafts department setting up crafts training centres, some intrepid young women have started enrolling at the centres. This could be seen as the beginning of feminisation of the labour process, challenging the belief that only men must practise this craft which can be classified as Khordad (undercut) Jalidhar (lattice), Vaboraveth (deep carving), Padri (semi-carving) and Saadikam (shallow carving)

In fact, the demand for the walnut carvings from Kashmir far outstrips the supply and, therefore, some of the work is now being outsourced to craftsmen in Saharanpur. As Basharat Bashir notes, "To meet the growing demand, traders in Kashmir link with artisans of wood carving in Saharanpur and fill the gap between demand and supply. The products from Saharanpur have contributed to the emerging demand for Kashmiri souvenirs available at a very reasonable cost to the visiting tourists." Obviously, this will not qualify for the GI tag, but rather than quibble over this, the main issue is that unless the incomes of the karkhanas and the karigars match their unique expertise, we are in danger of losing this exquisite craft to its faux versions.

Views expressed are personal