Brilliance beyond the badge

Meeran Chadha Borwankar’s eminently readable memoir ‘Madam Commissioner’ traces the author’s journey from her initial training to her notable roles as Police Commissioner and DG of prisons, showcasing her pioneering contributions to Indian policing, and her advocacy for intellectual over physical training

I must begin with a caveat. This is going to be a laudatory review, for Meeran and I grew up together in the BSF campus at Jalandhar Cantonment where our fathers were posted in the late seventies. Though a few years senior to me, and in different colleges, being in the same university saw us often competing with each other in the university debates and declamation contests. We also learnt horse riding from the same ‘ustads’ in the riding school at PAP Lines, and summer vacations were great fun in the salubrious campus, when life moved at its own, relaxed pace. When she made it to the IPS, it was a big moment for all of us in the campus.

A few years later, I joined the IAS, and though we have not had the chance to work with each other professionally, we have been Humphrey fellows, and have had the occasion to remain in touch. During my visits to Pune, I have seen her both as the Police Commissioner as well as the DG prisons, and in both these positions she left an indelible imprint. She is fearless and forthright in expressing her opinions in both the print and the electronic media, and we find that our general opinions are often aligned.

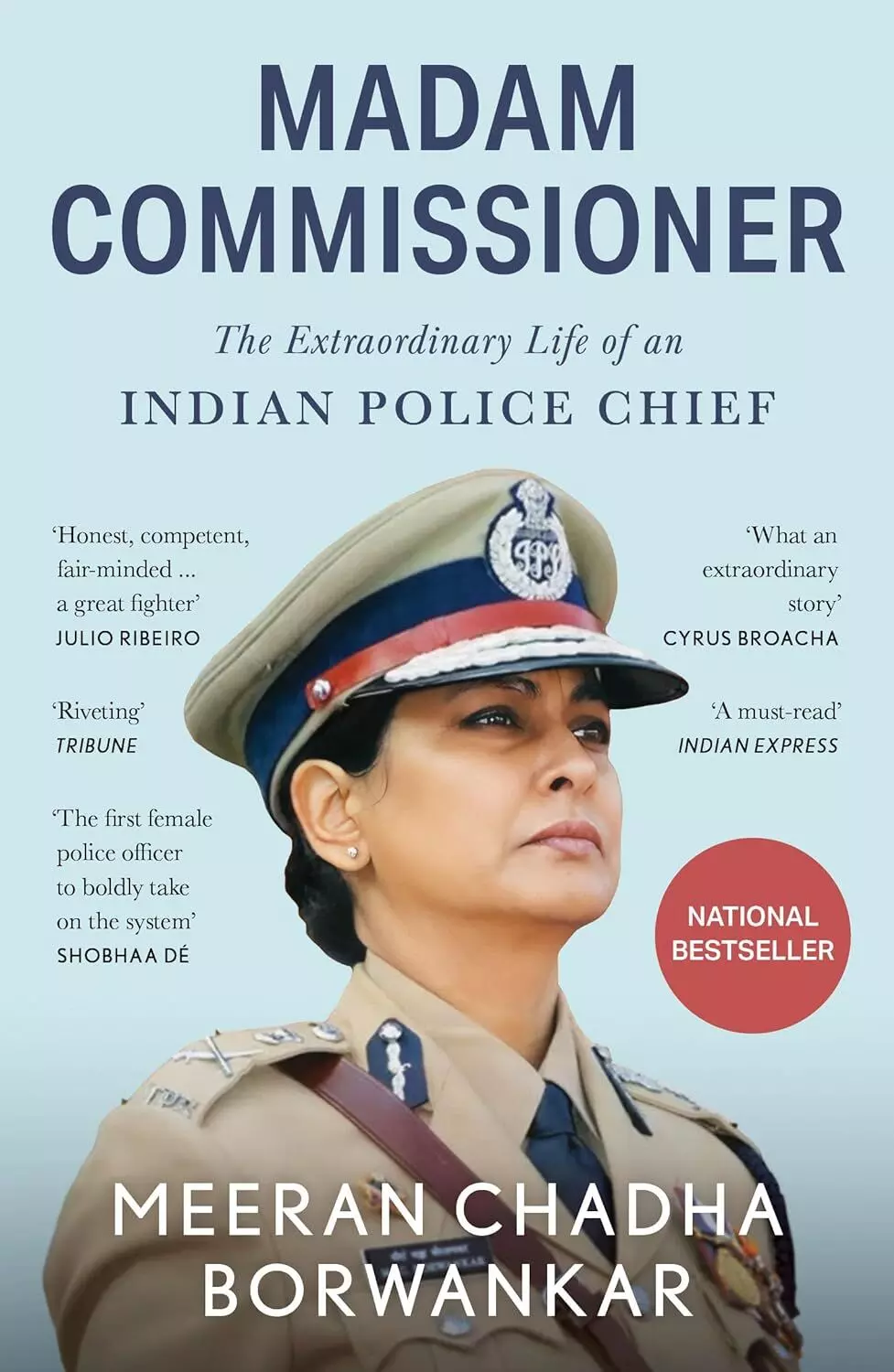

As such, it is a pleasure to review her eminently readable book ‘Madam Commissioner: The Extraordinary Life of an Indian Police Chief’. Each of the thirty-eight chapters, starting from her days as a probationer (as officer trainees were then called at the LBSNAA) in 1981, to ‘wheels of change’ when she moved out of the well-appointed office of the NCRB, the national repository on crimes and criminals, as well as the national digital police portal in 2017, reflects on one or another aspect of the life of a police officer who pioneered many firsts. As one cannot cover all the chapters, let me share some snippets which need to be placed on record for the next generation of officers of all services. The first is her tribute to her attendant Ganeshi and her Ustad Yadav – the former for ‘organizing’ her life at the Police Academy, and giving her sane personal advice, and the latter for instilling a sense of professionalism and perfection. She wonders why they don’t make Ustads like him anymore. She makes a very valid point that police training must shift from the physical to the cerebral – a point which I have also been making at all training conferences, but then the cops are so stuck with their macho image!

Meeran changed all this – as a young ‘mom-cop’ she carried out inspections with her young baby boy in tow, along with a maid, and the ‘protective driver’ Chougule, who would humor the boy with his jests. Balancing the personal with the professional, she agreed to delay her first independent posting in the district by staying on at Kolhapur as an Additional SP.

In one of the longest chapters in the book, ‘The Long Road to Justice’, in which the court finally sentenced a rapist to five years of imprisonment after a delay of eleven years, she reminds her readers of Benjamin Franklin’s lines “Justice will not be served until those who are unaffected are as outraged as those who are”. In ‘The Turning of the Tide’, she tells us how the timings of the tide affected a demolition operation which the Municipal Corporation and the Mumbai Police undertook in Dharavi – the biggest, and most dangerous slum of Asia. She also tells us that but for some ignoble exceptions, including that of a ‘six feet tall DCP’, the officers and men of the police force had stood their ground even during the gravest provocations during riots.

After five years as a DCP in Mumbai, she became the ‘first woman district police chief’ of Aurangabad (now Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar). She joined during the Ganapati festival – an eleven-day long festival which is celebrated with fervour and gusto, and she passed the ‘litmus test’ of maintaining peace in an otherwise communally sensitive and riot-prone district.

Meeran writes that by the eighties, corruption had become quite common – even among senior cops but she was in a state of shock when her immediate boss, the DIG, during an official inspection tried to browbeat a junior functionary for the same. Not only did she write a confidential note, which led to his transfer, and the end of his professional growth trajectory, she also earned the epithet Jhansi Ki Rani!

In ‘Nexus’, she tells us how politicians across political parties “like to ensure that Station House Officers (SHOs) are people of their liking. It is not that these officers are not competent...it is just that the rule of law is substituted by the rule of the politician” After all, the first loyalty will be to the person who assures them their lucrative posting. It is the same nexus which the NN Vohra committee talked about. And this is not a Maharashtra, or a police problem alone. Her Collector in Satara was transferred out because she had taken on the realtor’s lobby, and across the country this is known to all members of the IAS and the IPS. And yet, many continue with the ideals they imbibed in their training academies.

During her Humphrey Fellowship year, she got a chance to compare the functioning of the police in Seattle, San Francisco, and Atlanta. The US cops had a strict 40-hour work week, and could also work part-time outside of the police department – including as ‘bouncers’ in the local clubs to supplement their income legitimately. But to my mind the most telling comment about the state of public affairs and economic growth in India came from Professor Edward Schuh, who looked after the School of Public affairs: “the problem about the sluggish pace of progress in India is not ‘socialism or corruption’, but the failure to engage with academia”. Fortunately, this issue has been addressed in recent times, and the country is also on a high growth trajectory.

We now come to her tenure as the Commissioner of Pune Police. The main problem facing Pune Police was that unlike in the CBI and the Crime Branch in Mumbai, here officers were “running around in circles, attending to multifarious duties”. There were too many VIP visits, festivals, celebrations, agitations, protests, but innovative as she was, she took up three projects under community policing to build a strong rapport: the first was unpaid internships for students at police stations, the second was on strengthening police outposts called Chowki Sabalikaran, and the third was the setting up of study circles in police stations where local experts were asked to share their views on a wide range of subjects. All this goes on to show that what you need is not money, but creative imagination!

In fine the book offers an authentic kaleidoscope of the many facets of the life of an honest police officer. Even as she was aware that the ecosystem was getting compromised, she stood her ground for in the very long run, Satyamev Jayate does prevail. It is because of officers like her that the faith of the common citizen in the functioning of government is not shaken.

Her life is best expressed in these beautiful lines of Maya Angelou: “my mission in life has not been/merely to survive/but to thrive/and to do so with some passion/some compassion/some humour/and some style!”

The writer, a former Director of LBS National Academy of Administration, is currently a historian, policy analyst and columnist, and serves as the Festival Director of Valley of Words — a festival of arts and literature