Transcending the set contours

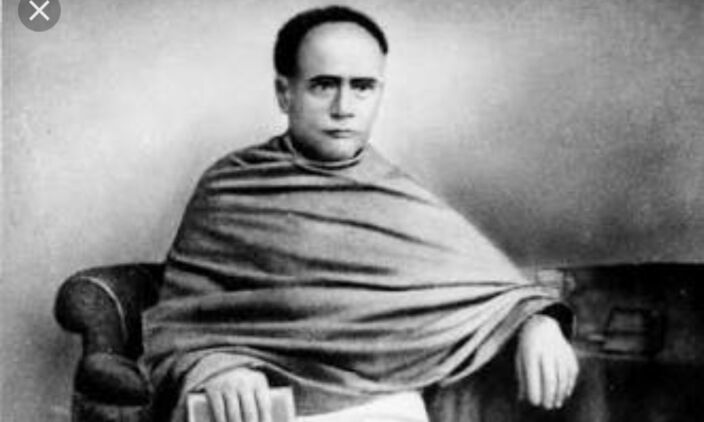

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, an administrator of the highest calibre, forged his traditional philosophy with pragmatic modernism to introduce required reforms and set high-standard ideals

In his famous essay, 'Tradition and the Individual Talent', TS Eliot pointed out that the process of poetic creativity is a result of traditional influence and individual imaginative prowess. Now, this theory also holds good beyond the canvas of literature, and when it comes to individuals who seem to have shaped the social history of their time, then certainly, it becomes even more relevant. Pandit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar is one such individual in whom we trace a combination of tradition and individuality which hovers over modernism. The noted historian, Amalesh Tripathi, has called Vidyasagar a 'traditional moderniser' — someone who has adhered to his philosophical legacy and yet never turned his face away from the contemporary demands for development.

Amidst the intellectual dearth and gloom of mid-19th-century India, Pandit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar shone as a beacon of light; someone who was not just displaying idealism in his conduct but also had knowledge about the problems of the age and concerning the remedy. Vidyasagar was perhaps the first intellectual of his generation to combine education with social order. He was smart enough to realise that education was the panacea for all the social evils of his time. Acting upon this understanding, Vidyasagar toiled hard throughout his life for improving the education scenario for his fellow countrymen fettered in the chains of illiteracy. While doing so he contradicted the conventions of his generation and set himself on the voyage of bringing notable social reforms like widow remarriage. He also advocated certain timeless notions in the field of education.

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar was a pragmatist who utilised his position in the domain of academic administration in British India. He had the opportunity to share his opinion with the policy-making ruling class, although it was not always a cakewalk for him. For instance, on more than one occasion, he had a conflict of opinion with Gordon Young, Director of Public Instruction. But he did not altogether succumb to the government machinery. As an academician, he stood firm on his ground. The abovementioned instance carries a lesson for any academic administrator even today, and that is, not to fall flat before any such government policy that is detrimental to the very ethos of education. Vidyasagar wanted an expansion of Western education; he also advocated for the introduction of English education in India. This reflects the traits of an educationist, a reformist and an administrator, who was reasonable enough to see the necessity of acquiring knowledge about the latest development of science and material philosophy. Indeed, to take the call of the hour, even by resisting conventional conservatism, is the hallmark of any able visionary and Vidyasagar displayed the same vision. His preference for moral education goes a long way to suggest the impending danger he could foresee hanging on the ethics of our society. He was rightly convinced that no policy on educational development could live to fulfil its purpose if the educated mind was morally degraded. Here, Vidyasagar stands modern because today erosion of the moral fabric in the social system is a global phenomenon.

In the matter of coining innovative ideas, Vidyasagar was an icon. During his administrative regime as Principal, he opened the gates of the Sanskrit College to all, irrespective of caste, creed or religion. He wanted educational institutions to be a melting pot of all cultures. These beliefs sustain his relevance in any age. Generations of academic administrators should be guided by this pluralistic attitude envisaged by Vidyasagar long ago. Vidyasagar was against indoctrination and he preferred discussions and debates. His suggestions to the Woods Dispatch in 1854 opened up a serious debate between the orientalists and occidentals. Vidyasagar accepted English as a medium of instruction in the education system but was also firm in convincing the committee that vernacular education cannot be ignored. Much because of his undaunted role, Woods Dispatch recommended vernacular medium of instruction with a tri-language formula, to remain fully prevalent. It is also interesting to note that the major recommendations of this committee, including training of teachers, female education, the opening of universities, grant-in-aid system for supporting educational institutions etc. were actually manifestations of Vidyasagar's mind. All these points still work with priority in the academic structure of the contemporary educational framework.

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar initiated some epoch-making decisions as an academician. One can hardly imagine the struggle he had to go through while implementing his ideas. Today, when we compare the present academic norms, we are bound to acknowledge our debt to Vidyasagar. It was he who encouraged the acceptance of admission fees and tuition fees in educational institutions. He was extremely keen on ensuring punctuality in attendance and maintaining discipline in classes. He also introduced summer holidays in the hot and humid months of May and June. Vidyasagar's emphasis on discipline, to be followed both by the teachers and students, is a path-breaking notion. As an academic administrator, he dared to tread on the path of propriety, and anyone looking after academic administration needs to do the same. As the Principal of Sanskrit College, he wanted to replace rote learning and suggested life-centric teaching. The modern education system dwells on lessons with practical demonstrations. Hence, the use of Information and Communication Technology has become so popular in teaching methodology. We are also equally concerned about the learning outcome of a child. Vidyasagar thought about it long back and, as a member of the syllabus committee, he stressed the development of vernacular education. It is in this context that his 'Bornoporichoy' played an effective role. He was badly criticized for inserting his own work in the curriculum but history has testified that his critics were not altogether correct.

In 1847, the famous English poet Matthew Arnold, who was also a school inspector, had expressed his apprehensions about the standard of primary education in England. Vidyasagar in contemporary India urged for the development of primary education as a step towards mass education. In 1853, he wrote a letter to Fredrick Halliday, the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, suggesting to him about the improvement of 'Pathshalas'. Realising the importance of consistent evaluation as a means of improving the learning process, Vidyasagar introduced the system of monthly tests. Initially, examinations were held annually. Modern academics rely on a recurring evaluation system for the gradual progress of the learners. Nowadays, government schemes like 'Kannyashree' or 'Beti Padhao, Beti Bachao' are introduced for providing financial help to female students. In the capacity of an educator, Vidyasagar played a key role in the formation of 'Narishiksha Bhandar' to the same effect.

It is a matter of utmost importance that a social reformer, who also holds the position of an academic administrator, should have an erect spine in the metaphorical sense. He should be bold, compassionate, innovative and holistic in approach. If he is in academics, learner-centric steps need to be administered. Vidyasagar epitomised all of these qualities with excellence. As an educator and social thinker, he is our contemporary — as even after 200 years his humanism is beyond transience. It is for us to decide whether we glorify him ceremonially or actually adopt his ideas and intentions.

The writer is an educator from Kolkata. Views expressed are personal