Measuring the gap

PGI-D, a central grading system rating the performance of districts, may reveal the true scale of primary education loss during the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has done more significant damage to education in India than we realise. The lack of data on the issue makes it all the more concerning.

On the first day of reopening schools after the summer holidays, teenage Nagma Khatun (name changed) was busy with her daily household chores.

The 14-year-old was in charge of the house, with both parents at work. She had to clean the house, fetch water from the public tube well, take care of her siblings, cook for them, feed them and do the dishes.

So when asked why she wasn't going to school, Khatun was ready with an answer. "I do not have time to go to school with so much work at home. Who will look after my brothers and sisters," she asked.

Embarrassed with the brashness of her own answer, she quickly softened her tone and explained herself. "I used to go to school and was among the class toppers. But studies during the pandemic were extremely challenging," Khatun said.

The story of hundreds of children

Her parents struggled to find odd jobs, having been laid off in the pandemic. There wasn't a spare smartphone in the house to attend classes, and education became a luxury for the teenager.

She had now forgotten all that she had learnt. "I don't want to go to school anymore. How would I keep up with other students? What do I say when the teacher asks me questions," she asked.

The girl hails from Mohanpur Gram Panchayat, a not-so-remote part of south Bengal and just an hour's drive from Kolkata.

Child Rights and You (CRY), a non-profit working for children's health, education and safety, found that Khatun's experiences resonate with hundreds of children across the country.

When schools reopened after almost two years of closure, it was found that many students had dropped out. They had taken up work or migrated to neighbouring states to support their families financially.

Many girls took ill-paid jobs as domestic help or were married off while still in their mid-teens.

With so many children permanently dropping out of education, it's no wonder that much of India's progress in educating less privileged kids over the past couple of decades has gone to waste.

When one tries to assess the scale of the loss, there is a huge scarcity of relevant data.

If we don't know how many children we have already lost, how would we plan to get them back? If we don't know how many of the remaining are vulnerable, how can we plan to retain them in schools?

A step in the right direction

The recent report on the Performance Grading Index for all districts (PGI-D) in India (2018-19 and 2019-20) is a welcome step towards that.

It was published by the Department of School Education and Literacy (DoSEL), which comes under the Union Ministry of Education.

The PGI-D gradation system has been designed and calibrated to map the status of school education against multiple indicators.

DoSEL decided to extend the PGI exercise to the district level in its latest leg to assess districts on a common parameter to gauge their relative status.

In the last two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the changes required in the existing school education system. Adopting digital learning as part of mainstream education didn't work very well. It couldn't reach a massive proportion of marginalised children, especially in remote and under-served communities.

Similarly, the gaps in effective classroom transactions are essential to understanding what activities and learning management translate into outcomes.

PGI-D has aimed to provide insights into the status of school education in all such categories, including learning outcomes, effective classroom transactions, infrastructure, facilities and more.

Hopefully, it will help catalyse transformational change in school education and assist stakeholders in identifying the gaps.

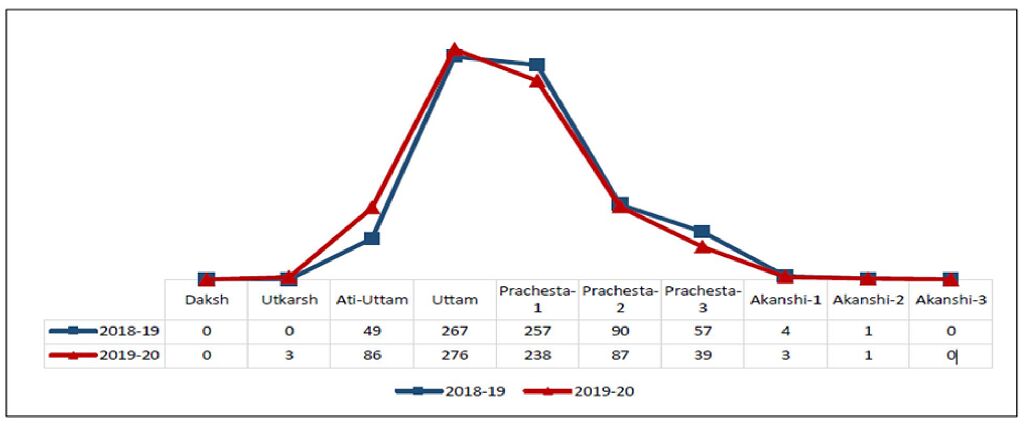

The report has presented us with findings from two consecutive years in the pre-COVID era (2018-19 and 2019-20) so far.

It would be interesting to see how the status changed during the COVID years as the findings of the subsequent editions of the report come in.

The summary suggested that none of the 733 districts got the highest performance grade in both 2018-19 and 2019-20.

Only three districts — Sikar, Jhunjhunu and Jaipur, all from Rajasthan — have achieved more than 80 per cent scores, the second highest grade.

CRY did a quick analysis of the report, which suggested that most areas in the country fall in the 51 to 70 per cent band.

The performance of the districts where CRY is involved in child education showed similar trends. There are 49 districts in the 41 to 60 per cent band in 2018-19 and 48 districts in 2019-20.

Similarly, 43 and 42 districts are in the 61 to 70 per cent range in 2018-19 and 2019-20, respectively.

This analysis shows that 90-odd districts with CRY's intervention programmes follow the overall national scenario.

It's still a long way to go when it comes to ensuring education for children, both in terms of quality and consistency.

Also, the fear is high that the more recent picture will be less optimistic. The years 2020-21 and 2021-22 fell directly under the shadow of the pandemic and child education bore its brunt.

But however grim the situation turns out to be, a deeper knowledge of the actual scale of the loss will help us plan accordingly. DTE

Views expressed are personal