Justice denied?

Despite the SC asserting a speedy trial as a Fundamental Right, fast-track courts continue to fail in India, bogged down by lacking initiative and procedure: writes Yash Agarwal

The Supreme Court of India had recognised speedy trial as a Fundamental Right as far back as 1986. We know how that has worked out in reality over the three decades since. Cases continue to languish, pendency continues to worsen and an ever-larger proportion of Indians continue to be deprived of the benefits of a well-functioning judicial system, dispensing timely justice.

Owing to the large scale vacancy in nearly all courts across the country and an ever-larger pool of litigants and citizens availing of judicial services, this has oftentimes come across as an intractable problem. One of the ideas to solve this problem of pendency and to speed up the dispensation of justice in India has been the setting up of dedicated fast-track courts.

Fast-track courts are ad-hoc institutions set up to deal with a particular type of cases, say ad hoc courts set up to deal just with cases involving sexual assault or POSCO, for example. Fast-track courts came about after the 11th Finance Commission made the recommendation of setting up 17,234 fast-track courts to ensure expeditious disposal of pending cases in the lower courts in 2000. In view of this recommendation, the Finance Ministry sanctioned Rs 502.90 crore to states as a "special problem and upgradation grant".

The idea was as follows. Fast-track courts were to be established by the respective state governments in consultation with the high court concerned and somewhere around five such courts were to be set up in each district in the country. For perspective, India has 718 districts today and in an ideal scenario that would put the number of fast-track courts in India at around 3,100. Reality is, we've less than 800 of them functioning at the moment.

Moreover, the National Law Commission had also recommended the setting up of permanent fast-track courts for commercial disputes and ad hoc fast-track courts to deal with other crimes in 2003 and 2008. The judges in these courts were to be selected by the respective high court concerned and candidates were to be drawn from primarily three pools, promotion of judicial officer members from existing eligible officers, retired high court judges and members of the bar council of the state concerned.

Over the years, the Union Government released Rs 870 crore to all state governments during the 2000-11 decade. In 2011, the Centre decided to discontinue funding for these courts, a decision which was challenged by states in the Supreme Court. Finally, for five years following that, the Union Government had to continue an element of central funding for the programme despite initially deciding not to, in wake of the Supreme Court's judgment in the Brij Mohan Lal case.

The Government of India provided funding limited to a maximum of Rs 80 crore per annum but this was contingent on the states matching the amount as an equal contribution. Many states decided to discontinue these courts altogether.

By the time this five year period came to a close, the 14th Finance Commission recommended the setting up of 1,800 fast-track courts across the country over the next five years.

These courts were to deal with a range of crimes involving children, women, senior citizens etc., and some civil disputes as well. The additional costs involved were estimated to be Rs 4,144 crore and this was provided for by the Commission in the form of additional tax devolution.

As per recent data, some 60 per cent of the fast-track courts as proposed by the Finance Commission are yet to be set up. In fact, some 15 states and Union Territories do not have even one fast-track court functioning.

Many states have simply chosen not to set up such courts at all. This is despite the fact that these courts were to be set up with a specific focus of dealing with heinous crimes especially those pertaining to women and children.

Fast-track courts exist for a very simple reason and function on an equally straightforward premise — dedicated courts tasked with the fast and efficient dispensing of justice for a particular category and type of crimes to those in need. Given this context, it is indeed baffling to come to terms with the fact that as per available research, fast-track courts have delivered worse outcomes than ordinary courts in India!

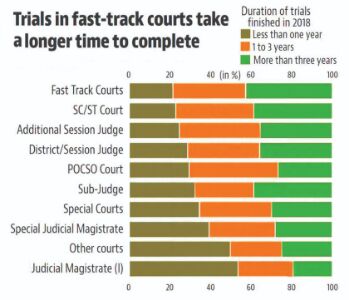

As per data of the NCRB for 2018, of the around 28,000 trials done in fast-track courts across the country in that year, 78 per cent took more than a year to complete and hence puts trial courts at the bottom of the rung in terms of time taken amongst all courts in India. In fact, around 42 per cent of the trials went on for more than three years and as many as 17 per cent of all cases took more than half a decade to complete.

There exists a significant inter-state disparity as far as performance on this front is concerned. For example, a vast majority of the cases with fast-track courts in Haryana and Chhattisgarh were disposed of in less than a year while courts in almost all other states which have fast-track courts finished less than 10 per cent trials in the same amount of time!

One reason for this could be that fast-tracks courts are not different from the usual courts in almost any major respect. They follow the same processes and procedures, the trials occur in the same way as they would in any court. In fact, these courts are often tasked with trials involving criminal cases and the most heinous of crimes, having been set up on an ad hoc basis for a particular type and category of crimes, to begin with. In view of these facts, it is not surprising at all just how far short these institutions have fallen off their stated mandate.

The provision of timely justice to all citizens is the ultimate public good. It is a service that only the state can provide for and there does not exist the scope of its private provision, to begin with.

It is rather appalling to witness the way the idea of these courts has been abandoned by most states in the country, especially when the expenditure involved is paltry relative to their annual budgetary spending. What is worse is the fact that some of the states which have no functioning fast-track courts as of today make it to the top ten in India in terms of crimes against women and children and hence the need for these courts is even greater. This must change.

Views expressed are personal