The state in the north

Building on the first part wherein dissatisfaction with ‘United Provinces’ was highlighted, this part shows how a new name came out of the blue, ruling out other considerations

As seen in the first part of the series, the debate over a new name seemed to settle over Aryavarta. The consensus, however, on renaming United Provinces (UP) as Aryavarta could not be reached out. There were 20 possible names which included (in alphabetical order): Aryavarta, Aryavarta Pradesh, Avadh, Bharat Khand, Brij Koshal, Brahmavarta Prant, Bhagirath Pradesh, Brahmadesh, Hindustan, Himalaya Koshlam, Himalaya Pradesh, Krishna Kushal province, Madhyadesh, Naimisharayana Pradesh, Nava Hindu, Ram Krishna Prant, Rama Krishna Pradesh and Uttarakhand. There were many 'letters to the editor' in newspapers like 'The Pioneer', 'The National Herald', 'The Leader' and 'Swatantra Bharat', among others — giving forceful arguments for one or the other name. The GB Pant cabinet decided to defer the decision as tempers tended to be frayed.

However, the decision could not have been postponed for longer. By October 1949, the Constituent Assembly wanted to finalise the names of the constituent units of India as "India was a union of states". As the matter continued to be contentious, Dr Rajendra Prasad felt that rather than debating the issue in the Constituent Assembly, it could have been best left to the state governments to finalise the name of the province.

While the Education Minister Sampurnanand was firmly in favour of Aryavarta, which apparently coincided with the majority view of the cabinet and the state legislature, it was decided to refer the matter to the Provincial Congress Committee. In the committee also, an overwhelming number of members supported this name. The name was endorsed by GB Pant, Sampurnanand, Govind Sahai, AG Kher, PD Tandon and Charan Singh. This, however, did not find favour from the Congress high command, and Pant had to retract the proposal as the name was not 'acceptable to other parts of the country'. The feeling outside of the province was that names like Aryavarta or Hindustan signified not merely UP but the whole of India. Constituent Assembly (CA) member from CP-Berar, RK Sidhwa, complained that UP (United Provinces) looked upon itself as the super-most province of India.

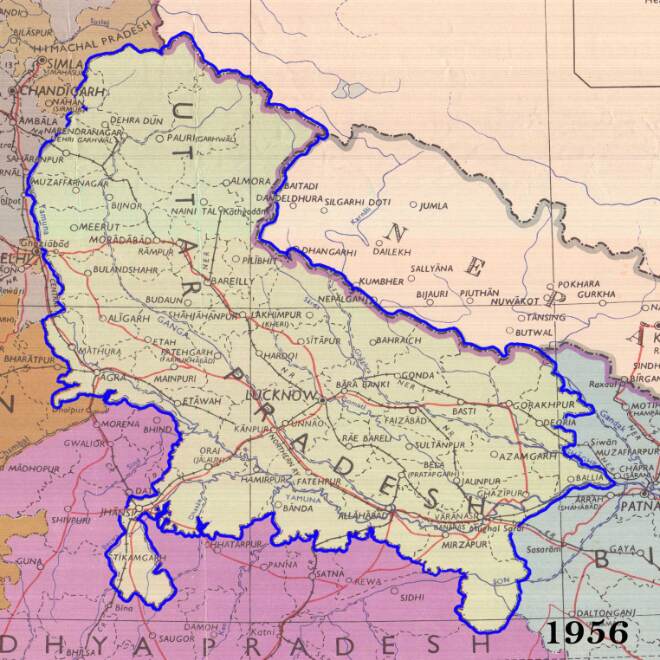

To break the deadlock, Dr Ambedkar moved a bill, which was adopted by the CA. It authorised the Governor-General to alter the names of provinces (as the states were then called). Meanwhile, Pant also agreed that names like Hind, Hindustan or Aryavarta will not be pressed for again. This was how Uttar Pradesh, a name that was not even put up for consideration became the new name of the state. Uttar Pradesh refers to the northern part of the country, and over a period of time, the region has evolved its own identity and resisted any attempt of altering its boundaries by the creation of any other state. It must be placed on record, however, that there was a very strong move in the early 1950s to create a new state, right on the borders of New Delhi besides, of course, the demand for a separate Uttarakhand.

The first formal challenge to the boundaries of UP emanated from a resolution of the Delhi Legislative Assembly, which "recommended to the Government of India that boundaries of Delhi be enlarged to include the neighbouring districts of Punjab and UP so that an administratively and economically sound unit is created". In fact, the memorandum submitted to the SRC on behalf of the Delhi government stated that "the people of this area (Delhi and the surrounding districts) have historic, cultural and economic ties. They have a common language, dress, marriage rites, laws of succession, system of land tenure and customs." The representation went on to add that the province of Delhi had been broken up artificially "both as a punishment for taking part in the so-called mutiny of 1857, as well as a device to break down their morale and crush their spirit'. The territories proposed to be included were Agra, Meerut and Rohilkhand divisions of UP; the Ambala Division of Haryana; and the Alwar and Bharatpur districts of Rajasthan. This proposal did not find a positive response, either from the Union government, or the states of UP, Punjab and Rajasthan.

What did cause a stir in the political circles of UP, and indeed in the Congress high command, was a memorandum submitted by 97 MLAs from the western and hill districts of UP wanting to merge their areas with Delhi. The five points made in favour of their demand were: a) the sheer size of the state, which often led to the neglect of the western districts and the hill areas; b) lesser development expenditure; c) need for rapid industrialisation; d) geographical proximity to Delhi rather than Lucknow and e) the new state would not need to develop a new capital as Delhi could serve the purpose.

The news that a hundred legislators could get together and submit a memorandum to the SRC caught the state and the Central leadership of the Congress unaware. They stepped in immediately to stall the move. Tandon and Pant closed ranks, and nipped this in the bud. They gave a counter-memorandum to the SRC on why the territorial boundaries of UP should remain unchanged. They averred that the large size of UP was actually good for large-scale development projects and for mobilisation of resources. While the Chairman of the SRC Justice Fazal Ali and HN Kunzru were convinced with this argument, the third member, KM Pannikar gave a strong note of dissent. He made the point that UP was too large to be administered effectively. Dr Ambedkar also expressed the view that a state of the size and population of UP was actually creating political asymmetry.

The writer is the Director of LBSNAA and Honorary Curator, Valley of Words: Literature and Arts Festival, Dehradun. Views expressed are personal