Seeds of disintegration

The migration trend from Eastern Bengal to lower Assam, set by 1905 Partition, acquired religious colour on account of politics and, as 'integration' efforts through the Sixth schedule bordered on 'assimilation', highlanders' discontent set the stage for Assam fragmentation

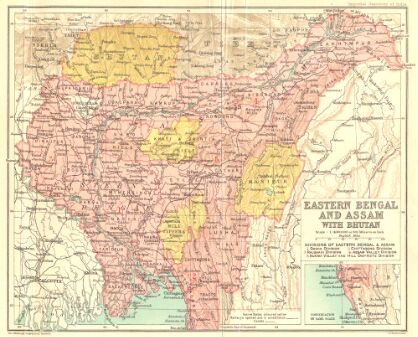

The Partition of Bengal in 1905 witnessed the creation of a new province — Eastern Bengal and Assam. Dhaka, Chittagong and Rajshahi divisions were cut off from Bengal, and lumped with Assam, to carve out a new province. Rajen Saikia called this "the second vandalization of the political geography of the region". This 'short-lived artificial province' came to an end with the annulment of the Partition of Bengal in 1911. However, the political geography of the fleeting province had devastating results in the long run for the state of Assam. This was the period of 'open sesame' for migration of peasants from Eastern Bengal to the lower Assam districts. The Chittagong port and Lumding railway line in central Assam became the highway of migration — changing the demography of the state permanently.

Although the Congress — under the leadership of Gopinath Bordoloi — won the highest number of seats in the provincial elections, it decided to sit in Opposition. This gave Sir Saadullah Khan of the Muslim League an opportunity to become the premier of the province. Sir Saadullah not only wanted the abolition of the Line System, he also encouraged settlement of Muslim immigrants to make Assam a permanent base for the Muslim league. His 'grow more food' or 'Land Development Scheme' was turned down by the Viceroy Lord Wavell as a ploy to 'grow more Muslims'. Saadullah's sixteen-month regime was not exactly popular, and given the contradictions within his rag tag coalition, he had to resign in August 1938. Gopinath Bordoloi then formed the Congress Ministry in Assam, and amongst his first steps was the reversal of Saadullah policy of encouraging Muslim immigration to Assam. Bordoloi felt that the 'unrestricted occupation' might drive away the indigenous inhabitants; the (Congress) government prohibited the settlement to persons who came after January 1, 1938. Bordoloi had to resign again when British India joined World War II, and Saadullah again replaced him as the Premier till 1946. Saadullah's premiership brought about the demographic transition in Assam which led Jinnah to remark to his Private Secretary Moin-ul-Haque Chaudhury: "Wait, I shall present you Assam on a silver plate".

The establishment of the Dominions of India and Pakistan was no deterrent to the influx of the Bengali Muslims into Assam. Despite the Pakistani Passport System, Pakistan (Control) Act and Migrants Act 1950, the inflow of migrants continued unabated. As the earlier migrants had settled down in the districts of Assam bordering East Pakistan, the newcomers found no difficulty in crossing the porous borders and settling down through the matbars or petty zamindars.

In the immediate aftermath of independence, the entire province was in turmoil. Though, the Sixth Schedule was applied mutatis mutandis to the 'excluded' and 'partially excluded' areas under the Government of India Act of 1935, under which an Autonomous District Council of not more than 24 members was invested with legislative powers to formulate laws for administration of land, management of non-Reserve forests, regulation of jhum cultivation, appointment and succession of chiefs, and matters having a bearing on personal and social life of the tribals. The council was empowered to set up various types of courts (including appellate ones); construct and manage primary schools, dispensaries and roads; and prescribe the language and manner in which primary education shall be imparted. They had the power to assess and collect land revenue on the same principles as followed in the states, and to levy and collect certain taxes. Thus, while the tribals in other states were governed by the Fifth Schedule, the tribes of Assam hill tracts were accorded autonomous status under the Sixth Schedule. More significantly, unlike panchayats in other parts of India, the district council had parallel legislative powers alongside the state government with respect to certain subjects. They also had a 'separate budget head' in the general budget of the state. They enjoyed exemption from payment of income-tax, reservation in services, and special facilities for students in matters of admission to educational institutions, besides scholarships and stipends.

However, even with the best intention of the framers of the Constitution, the councils could not achieve their intended objectives. While the Nagas rejected it outright, the remaining five councils — Garo Hills, United Khasi and Jaintia Hills, Lushai Hills, United Mikir (Karbi) and North Cachar Hills — also started on an inauspicious note as Assam was most reluctant to give up any powers. The chauvinistic elite of Assam wanted to hasten the extension of Assamese influence into the interior of the hills. Unfortunately — for them as well as the diverse ethnic groups in the state — they could make no distinction between 'integration' and 'assimilation', and here lay the genesis of the fragmentation of Assam. Constant harping on assimilation with 'Greater Assam' alarmed the highlanders regarding their land, language and cultural identity.

Views expressed are personal