Northeast frontiers

During the late 19th century, the Assam frontier had several geographical additions and the region underwent demographic transformation with variegated groups bringing in their own set of distinctive character

The 'making' and 'unmaking' of Assam goes on to show how 'frontier boundaries' have played a seminal role in the political history of this region. Assam was a frontier state not only in British India, it has been so from the times of the Mahabharata. Even for the Mughals and the subedars of Bengal, it was the last outpost. The many changes in the frontiers of this state therefore make a very interesting story!

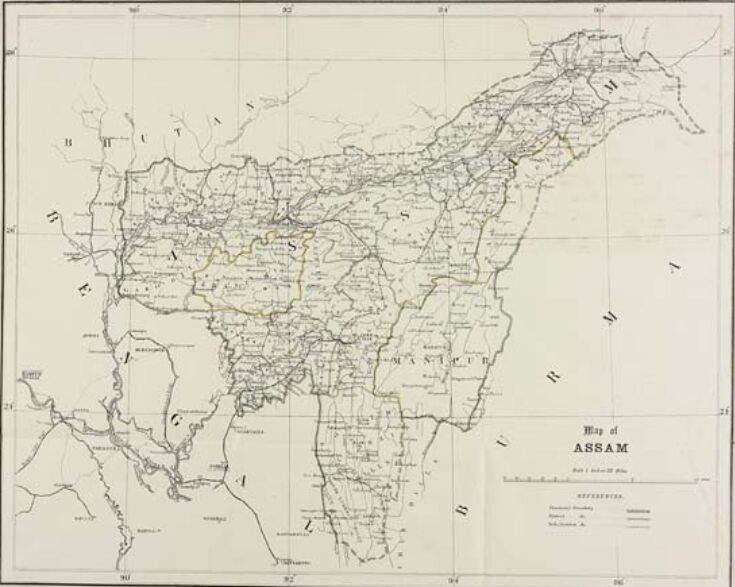

In most writings on Assam, it is assumed that the story starts when Assam became a Chief Commissioner's province in 1874. However, this 'Assam' was different from the Ahom kingdom on the Brahmaputra valley which comprised the districts of Goalpara, Kamrup, Darrang, Nagaon, Sibsagar and Lakhimpur. All of these, with the exception of Goalpara, were taking a distinct shape in the 19th century — with Guwahati as the headquarters of the provincial administration. In 1874, four new districts — Cachar, Garo Hills, Khasi, Jaintia Hills and Naga Hills — were appended to Assam.

Sylhet too was brought under Assam in September of the same year. As Rajen Saikia has noted: "This was the beginning of the separation of the political geography of the region from its social and historical roots". Two decades later, the Lushai Hills district was also added.

However, it must be pointed out that the annexation of the Garo Hills, the Naga Hills and the Lushai Hills by the British was a violation of the Queen's proclamation of 1858 which promised the end of the era of territorial expansion of the empire in India.

The first Chief Commissioner of Assam, Col Richard Harte Keating, assumed office in February 1874 at Guwahati, but shifted the capital to Shillong. The move was opposed by the 'Bangabandhu' of Calcutta which said: "Guwahati was the centre of the province, had a good climate and a better claim as a capital than Shillong which was not connected by good roads." The annexation of the districts of Cachar and Sylhet also came in for intense criticism. Historian JB Bhattacharjee called this the first partition of Bengal: "Surma valley being a natural continuation from Bengal plains and populated by the Bengalis, it was logical that Cachar and Sylhet should continue as parts of Bengal."

But the real change in the profile of the state came from the intertwined factors of Christianity and the Inner Line Regulation issued under the Bengal Frontier Regulations, published a year ago in 1873. These transformed the cultural, social, educational, denominational and political landscape of the hill districts. The torchbearers of Christian proselytization were the American Baptists in the Naga and Garo Hills, and the Welsh Missionaries in the Mizo, Khasi and Jaintia Hills. Although criticised as the indirect instrument of colonial control, there were positive aspects as well: The Church brought about a total change in the outlook of the head-hunting tribes by ensuring the development of local languages, publication of dictionaries and grammar, popularisation of English, expansion of secular education, measures of healthcare and cultural change etc. However, the 'nationalist' opinion was rather sceptical of the missionary role, especially with regards to proselytization. One reason for the success of the missionaries was the disdain with which the Assamese elites looked upon the hill tribes. "They did not have any curiosity about the hillman — his food, dress, hearth and home. Localised border trade helped them realise the benefit of friendly relations. But there was no promise of long-term friendship from either side."

Let it also be added that while the ILR was designed to be a protective measure for the security of the British subjects, it did not recognise any "pretension to sovereignty of the hill tribes living beyond that imaginary line". However, the ease with which the missionaries were allowed to cross the ILR for evangelical work and conversion did raise questions about the real intent of the colonial administration, all of whom were Christians, and even after Indians started joining the ICS, there was a deliberate attempt at keeping them away from the Assam hill districts.

The demographic transformation of Assam had started with tea plantations — it was easier earlier to manage 'coolies' from outside than insiders. The planters preferred tribals from Central India as the workforce and Bengalis in supervisory roles.

Just as the planters needed Bengali clerks, the administrators who were making a transition from 'Persian' to English and Bengali, as the administrative language began to depend more on the Bengalis, they became the intermediary ruling class.

The third group that stepped into Bengal was the Marwari business class which monetized the economy for the native Assamese who were just not inclined to change their set mores. The Marwaris reached the farthest interiors with finished goods and extracted disposable surpluses. Then there were the Nepali workers who were engaged in road construction, coal mining and other sectors which required hard physical work. Last but not the least were the Muslim agriculturists who brought new land as well as 'char lands' under the plough, and transformed the landscape with their distinct sartorial identity as well as places of worship. Their integration with the Assamese society was a major challenge as, unlike the Santhals, the Marwaris, the Bengalis and the Nepalis, they were not part of the larger Hindu pantheon.

Views expressed are personal