An independent J&K?

While Jinnah’s bid for Muslim support was contested by Abdullah’s secular image, he also found little success in tempting Maharaja on his side who was lost in his own dream of an independent state

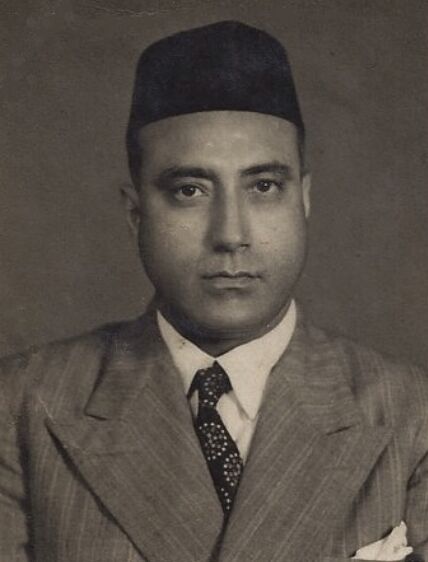

Sheikh Abdullah's proximity to the Congress upset the plans of Jinnah and the Muslim League who were was banking on the Muslims of Kashmir to garner support for their demand for Pakistan. The Muslim League always liked to highlight that Sir Mohammed Iqbal, the other prominent Kashmiri, was backing the demand for Pakistan, but Sheikh was both secular and democratic. When Jinnah visited the state in 1944 and advised the Muslims of the state to be organised under the banner of the Muslim League, he met with stiff resistance. So much so that the only public meeting which Jinnah attended broke up amidst shouts of 'go back Jinnah'. It is on record that Jinnah had to be escorted to a safe place by the state police. Though he did succeed in reviving the Muslim Conference under Ghulam Mohammad Abbas, the party faced a profound dilemma. While it was virulent in its opposition to the secularism of the National Conference, it also realised that its arch-rival, Sheikh, was indispensable to its goal of integration of Kashmir into Pakistan.

In May 1946, Sheikh Abdullah launched the Quit Kashmir agitation against Maharaja Hari Singh for which he was arrested and sentenced to three years of imprisonment. He was released after 16 months in September 1947 with the intervention of Nehru and Gandhi. Incidentally, the MC leader Ghulam Abbas had also appealed to the Maharaja to release Sheikh, following which he too was arrested.

Thus, on the eve of Indian Independence, the two political organisations in Kashmir — the National Conference and the Muslim Conference — both of which were Muslim-led and largely Muslim-supported, had their leaders were behind the bars. To achieve anything substantial the two had to be brought together but the attempts to reconcile Sheikh Abdullah with Jinnah failed "because both men being conscious of their own position and importance, neither could bring himself to make the first move".

Meanwhile, it was becoming clear to the Rulers of the princely states that Britain was likely to renege on the commitments it had made to them because, after the Second World War, it simply did not have enough financial or military muscle. The larger states — Travancore, Hyderabad and J&K — started looking at 'independence' as a possible option. However, they had limited exposure to the actual grind of politics, for their internal autonomy had been guaranteed by the Raj. They lived in their own world of gun salutes, shikar parties and ceremonial pomp with limited understanding of what their subjects really wanted. Their Prime Ministers too were not masters of political acumen for they owed their position on account of their personal loyalty to the King. They were both perpetrators and victims of the court politics where rival factions were keener on consolidating their power rather than furthering the interests of the state. In Jammu and Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh felt that he could perhaps manoeuvre an independent kingdom for himself. He instructed his Prime Minister Ram Chandra Kak to bide time. "He disliked the idea of becoming a part of India, which was being democratised, or of Pakistan which was Muslim…..He thought of independence". Hari Singh saw the independence of Jammu and Kashmir as an alternative and viable option and Kak fuelled his desires, making him believe Jammu and Kashmir can be an independent country.

This was also the time when an occultist by the name of Swami Sant Dev made his appearance in the court of Hari Singh and began to exercise considerable influence. He was described as the Rasputin of the court of Kashmir on account of his proximity to Maharani Tara Devi. Kak had reservations about him but, in the power tussle between the Swami and the Prime Minister, the round was won by the Swami, and Ram Chandra Kak was dismissed unceremoniously (and arrested on August 11, 1947). Before Kak lost the favour of his Maharaja, both were clearly united in their antipathy to the Congress and Sheikh and held parleys with Jinnah who offered them the blank cheque, as he did for other Rulers of the border states (Jodhpur, Jaisalmer) in his bid to expand the territorial boundaries of Pakistan. Kak was the fall guy. It suited all the parties — Congress, Sheikh and the Maharaja — to apply the 'traitor' tag to him. In his memoir, Kak described the role played by the Indian National Congress in the affairs of Jammu & Kashmir from 1938 onwards, including the propping up of Sheikh to counterbalance the influence of the Maharaja. He felt that Sheikh's influence was limited to the Kashmiri Muslims of the valley but the larger-than-life image was due to his association with the Congress.

Jinnah and his team had been more than willing to cut a deal with the Maharaja which would exclude the Congress and the Sheikh. In July 1947, Mohammad Ali Jinnah wrote to the Maharaja promising him "every sort of favourable treatment" followed by the lobbying of the state's Prime Minister by leaders of the Muslim League. The Maharaja was promised complete internal autonomy within his state, including an assembly with a majority of nominated officials, for Jinnah was not exactly a paragon or patron saint of democratic virtues. However, Maharaja should be credited as he resisted all these tempting offers and also politely declined Jinnah's request to visit the state as a private citizen for medical recuperation. He knew that Jinnah's presence could be a spur for the Muslim Conference to brew fresh trouble.

Views expressed are personal