"The Battle of Belonging" | The end of autonomy

Firmly anchored in incontestable scholarship, yet passionately and fiercely argued, Shashi Tharoor's The Battle of Belonging unambiguously establishes what true Indianness is and what it means to be patriotic and nationalistic in the 21st century; Excerpts:

Author: Shashi Tharoor

Publisher: Aleph Book Company

As I have noted, Prime Minister Modi likes to practise what American generals call ‘shock and awe’. The most egregious examples of this have been mentioned in the previous chapter—the utterly misguided abrupt demonetization of 86 per cent (in value) of India’s currency, and the sudden lockdown of the country against COVID-19 in March 2020—and resulted in consequences that the nation is still dealing with. In August 2019, he added one more to the growing list of dramatic snap decisions whose repercussions he did not appear to have fully calculated.

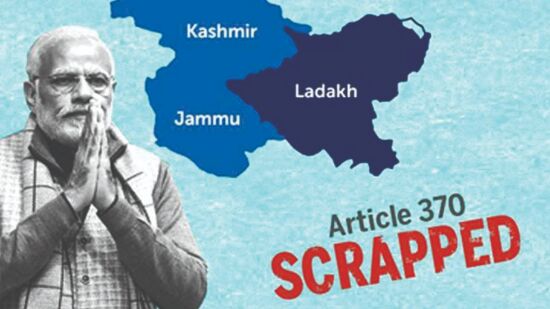

On 5 August 2019, Modi shocked the nation with an announcement on Kashmir that could well turn out to be the political equivalent of demonetization. After seven decades of assuring the people of Jammu and Kashmir, and the international community, that the state would continue to enjoy special autonomous status under the Indian Constitution, the Modi government announced that day that it had unilaterally divided the state, carving out a union territory in the high plateaux and hills of Ladakh in the eastern half of the state, and reducing the remainder—still named Jammu and Kashmir—from the status of a state to that of a union territory. The resultant outcry brought the vexed question of Kashmir back onto the top of the international agenda.

When the British quit India in 1947, the 544 ‘princely states’ (nominally ruled by assorted potentates but owing allegiance to the British Raj) were required to accede to either of the two new states, India or Pakistan. The Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir—a Muslim-majority state with a Hindu ruler—dithered over which of the two to join, and flirted with the idea of remaining independent. Pakistan, determined to wrest the territory, sent in a band of irregulars, who made considerable inroads before being distracted by the attractions of rapine and pillage. The panicked maharaja, fearing his state would fall to the marauders, acceded to India, which promptly para dropped troops who stopped the invaders (by now augmented by the Pakistan Army) in their tracks. India took Pakistan’s invasion to the UN as an issue of international aggression. When a ceasefire was declared, India was left in possession of roughly two-thirds of the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

To ascertain the wishes of the Kashmiri people, the UN-mandated a plebiscite, to be conducted after the Pakistani fighters had withdrawn from the territory they had captured. India had insisted on a popular vote, since the Kashmiri democratic movement, led by the fiery and hugely popular Sheikh Abdullah, was a pluralist movement associated with India’s Congress party rather than with the Muslim League that had demanded the creation of Pakistan, and New Delhi had no doubt that India would win a plebiscite. For the same reason, Pakistan refused to withdraw from the territory it had occupied, and the plebiscite was never conducted. The dispute has festered ever since.

Four wars (in 1948, 1965, 1971, and 1999) have been fought across the ceasefire line, now dubbed the Line of Control (LoC), without materially altering the situation. In the late 1980s, a Pakistan-backed insurrection by some Kashmiri Muslims, disaffected by ballot-rigging in the state elections of 1987, augmented by foreign militants infiltrated across the LoC and supplied with arms and money by Pakistan, began. Both the militancy, and the response to it by Indian security forces, have caused great loss of life, damaged property, and all but wrecked a Kashmiri economy dependent largely on tourism and the sale of handicrafts and carpets. In the process, both countries have suffered grievously: India, whose citizens have been killed in large numbers, and which has had to deploy over half a million men under arms to keep the peace, and Pakistan, whose strategy of ‘bleeding India to death’, through insurgency and terrorism, has accomplished little of value, while making it is military enormously powerful within Pakistan and disproportionately well-resourced (largely thanks to Kashmir, the Pakistan Army controls a larger share of its national budget than any army in the world).

Amid this stalemate, the revocation of Article 370 of the Constitution of India (and of Article 35A, which permitted Kashmir to define its ‘state subjects’ and to restrict the rights of others to acquire or inherit a property in the state) is meant to be a game-changer. The government’s defenders argue that autonomy had only enhanced a sense of separateness in the Kashmir valley, that it had not prevented the region experiencing large-scale separatist violence, that it had permitted a growing Islamicization marked by the ethnic cleansing of the Hindu Pandits from their traditional homes in the valley, and that the special status prevented progressive Indian laws and court rulings (such as those assuring affirmative action to ‘Scheduled Castes’, the Dalit community) applying to the state. All this is true, but it had happened despite Article 370, not because of it.

The stripping of special status, apologists also argue, would ensure more economic development in the state, since non-Kashmiris would be free to buy land and would invest more freely. Indeed, in the first two weeks since the revocation was announced, the governor publicly invited out-of-state investors for a conference; big corporations, including India’s biggest, Reliance, have conveyed their intention to start projects in the state; and Bollywood producers have been tripping over themselves to book all possible titles for future blockbusters to be made in and about the state. Most distastefully, politicians in other states have suggested their gender-balance problems could be more easily overcome through the import of fair Kashmiri girls. All of these initiatives fizzled out in the sullen lockdown that followed in the area for several months afterwards.

Many, however, worry that, as with demonetization and Modi’s COVID-19 strategy, the short- and medium-term damage caused by this decision will greatly outweigh the theoretical long-term benefits. First and foremost is the violence to India’s democratic culture: the government has changed the basic constitutional relationship of the people of Jammu and Kashmir to the Republic of India without consulting them or their elected representatives. Indeed, it locked them up, depriving Kashmiri democrats of the very voices that had spoken for them within the Indian constitutional space. One former chief minister, Omar Abdullah, was incarcerated for 232 days; another, Mehbooba Mufti, remains in detention as these words are written, more than a year after her arrest, as does veteran Congress leader and former union minister, Saifuddin Soz. This is a breathtaking betrayal of our democracy and nothing short of legislative authoritarianism.

It could also be done to other states in future. The Kashmir episode was a reminder of a timeless lesson—that constitutional promises made by governments should never be broken, especially through manoeuvres that are so questionable, because that sets a precedent that, if emulated elsewhere in the country, could in due course destabilize the whole republic. The legal sleight of hand that enabled the changing of the status of Jammu and Kashmir was blatant. By claiming that (as the Indian Constitution requires) the concurrence of the state of Jammu and Kashmir was obtained, when it was under President’s Rule, and translating ‘state’ to mean the governor New Delhi itself had appointed, the government had, in effect, taken its own consent to amend the Constitution! Worse, the decision was brought to parliament (where the ruling party’s majority guaranteed its prompt passage) without consultation with the local political parties; with the Jammu and Kashmir state legislature suspended for more than six months; and, with democratically elected political leaders under ‘preventive’ detention.

There is no question that the legal issues merit more detailed consideration, and the public, which has largely applauded the outcome, needs to be fully apprised about any legal sleight of hand that might have taken place. Equally, the Indian people need to know whether constitutional provisions were breached or worked around.

A few basic facts: Article 370 was conceived as a temporary measure until the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir was formed, and it was left to the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir to determine the constitutional relationship between the rest of India and the state. It is because the primacy in such matters lies with the people of Jammu and Kashmir that Article 370 (3) states that Article 370 could only cease to exist through a presidential order after obtaining the recommendation of the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir to end the operation of the article.

The Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir enacted the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir, whose Article 147(c) prevents the state’s legislative assembly from doing anything that would affect the constitutional relationship with India, as provided in the Constitution of India. Thus, they accepted Article 370 as the permanent constitutional relationship between the Union and the state, an interpretation upheld in successive Supreme Court judgements.

The consent of the people of Jammu and Kashmir, through their elected assembly, is essential before a government can alter its special status under Article 370—Clause 3 of Article 370 makes it clear that one cannot amend the article without the recommendation of the constituent assembly.

However, the government tried to be clever, by amending Article 367 to indirectly amend Article 370, saying that the constituent assembly shall mean the legislative assembly. What was the purpose of this amendment? Because it could then argue that due to the operation of President’s Rule in the state, the role of the legislative assembly had devolved upon the parliament in New Delhi—which could give the recommendation instead of the legislative assembly because the assembly had been dissolved.

However, the government had completely ignored the well-established position in law that whatever you cannot do directly, you cannot achieve indirectly. It did not have the right to amend Article 370 without obtaining the consent of the people; it, therefore, could not indirectly amend it in the absence of their consent. The Supreme Court has recognized that while something can be formally legal, the substance of it can be unconstitutional, a judgement that on this matter the Supreme Court has, in its wisdom, chosen not to make.

Excerpted with permission from Shashi Tharoor's The Battle of Belonging; published by Aleph Book Company