The story of looming disasters

Be it the mountains around Joshimath or the mines in Jharia-Ranigunj, the ignorance regarding the sensitive terrains, resulting perhaps from vested interests, has increased the potency for disasters like land subsidence manifold

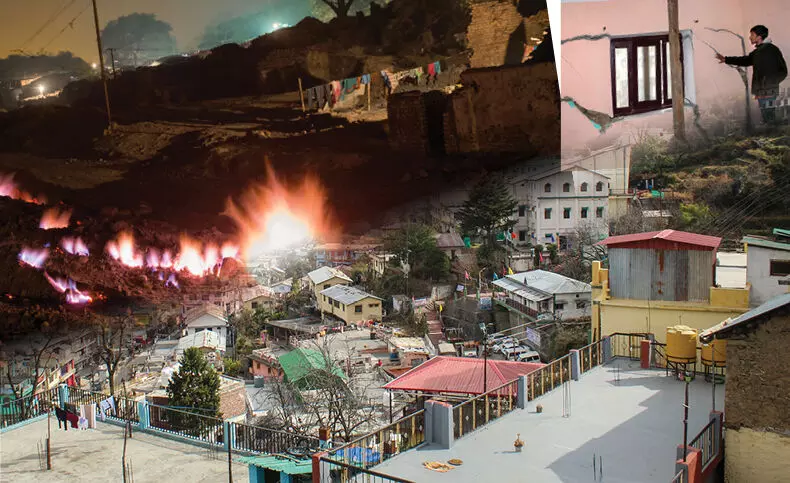

The ancient pilgrim town of Joshimath is sinking. Residents are forced to flee their homes in the freezing weather of January. Walls have cracked open, foundations are tilting and sinking. Experts point out that this was a disaster waiting to happen because the authorities ignored multiple warnings over decades about the way roads and hydropower projects were being built. The Prime Minister’s Office declared Joshimath a “landslide-subsidence zone” and asked experts to prepare short- and long-term plans on what to do, reports Scroll. Uttarakhand chief minister Pushkar Singh Dhami claimed that the land subsidence in the township was because of “unscientific” development work though he described it as a “natural disaster”, reports Hindustan Times.

Indian Space Research Institute (ISRO) released data showing that Joshimath had sunk 5.4 cm between December 27 and January 8. Meanwhile, as per a report by Rediff.com, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) has advised — through an office memorandum dated January 13, 2023 — ISRO and other government agencies to refrain from interacting with media on the Joshimath disaster.

Joshimath is located on a ridge cut through by streams that descend from Vishnuprayag where Dhauliganga and Alaknanda rivers converge. Serious apprehensions were expressed in 2013 that the tunnels of the Tapovan-Vishnugad Hydropower Project of the NTPC could cause huge damage, reports Lokmarg. The government did not pay any heed to that warning.

In addition to the unviable hydropower projects, the 125-km Rishikesh-Karanprayag railway line, being constructed reportedly at a whopping cost of Rs 20,000-crore, will lead to the construction of 35 bridges and 17 tunnels. Contractors have cut lakhs of trees for the multi-lane expressway for the ‘Char Dham Yatra’, the pet project of the prime minister. This has made an extremely damaging impact on the fragile Himalayan ecosystem. In December 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi laid the foundation stone for Chardham all-weather road project. Out of 53 packages covering a total length of 825 km of the Chardham Road Project, 21 packages covering a length of 291 km are complete. Ironically, the Prime Minister described this Rs 12,072 crore project as a tribute to those who lost their lives during the 2013 flash floods in Uttarakhand.

Although the recent Joshimath incident has rekindled apprehensions about the future of other fragile hill stations, Gangtok, Darjeeling, Nainital, Shimla et al, the environmentalist and media are conspicuous by their deafening silence on the future of coal cities of Jharia (Jharkhand) and Ranigunj (West Bengal) which are facing similar risks, if not more, of subsidence due to burning of the coal seams, for over a century, underneath these cities. Both Joshimath and Jharia are examples of the failure of the state to appreciate the distinct characteristics of the fragile mountains and mines while planning and executing projects for ‘development’. In this piece, we shall briefly discuss these two looming disasters which have been in the making for decades.

Joshimath

Joshimath is a prominent religious place for Hindus, as one of the four famous Peeths, established by Adi Sankaracharya, is situated here. It is believed that Adi Shankaracharya came here to meditate and eventually established a pilgrimage after he achieved ‘Jyoti’. Originally called Jyotirmath, today, Joshimath is the entrance point to numerous trails and ancient routes among the snow-clad mountains. When Badrinath temple remains closed for winter every year, one idol of Lord Badri is brought to Narsinh temple in Joshimath and worshipped for six months. Considered the ‘gateway to heaven’, this ancient temple town is also a preferred destination for trekkers and nature lovers. Nanda Devi, the tallest mountain, is reached only through the roads of Joshimath.

Though experts have repeatedly cautioned about the danger of the fragile ecosystem of the region where Joshimath is situated and advised authorities to take appropriate measures to avoid disaster, reports suggest that the government has not paid any heed to those warnings. Professor YP Sundriyal, a noted geologist and environment activist of the region, in his recent article, reminded us that a formal warning of such a possible catastrophe came forty-six years ago. According to him, Joshimath’s foundation has always been very weak. It is located in seismic zone five and is bound by two regional thrusts — Vaikrita in the north and Munsiari in the south. The 1991 and 1999 earthquakes proved that the area is susceptible to earthquakes. Furthermore, the town, which at present has over 4,500 buildings, is built on a palaeo-landslide-prone slope.

Sundriyal also mentioned the warning made in 1985 by three eminent scientists, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Navin Juyal, and MS Kunwar, in their article Vishnu Prayag Project: A risky venture in Higher Himalaya. The essay mentioned how during the ramping up of the infrastructure, including the building of roads and houses, for the development of Joshimath, enormous quantities of earth and boulders were removed using dynamite. They also mentioned that irregular drainage had made the slope vulnerable to erosion. As a result, many parts of the town sank, reports New Indian Express.

As early as the 1960s, the Union government had appointed MC Mishra, the then collector of Garhwal, to look into why Joshimath was sinking. The report submitted, in 1976, by the 18-member committee clearly mentioned that Joshimath was situated on an old landslide zone and could sink if development continued unabated, and recommended that construction be prohibited in Joshimath. After the recent incident, the prophetic observations of the Mishra Committee report have surfaced again. Among others, the important observations of the committee were:

Joshimath lies on an ancient landslide, resting on a deposit of sand and stone, not rock. The rivers Alaknanda and Dhauli Ganga play their part in triggering landslides, by eroding the river banks and mountain edges. It’s believed that increased construction activity and growing population have contributed to frequent landslides in the area.

“Joshimath is a deposit of sand and stone — it is not the main rock — hence it was not suitable for a township. Vibrations produced by blasting, heavy traffic, etc., will lead to disequilibrium in natural factors…” the report had stated.

Lack of proper drainage facilities also leads to landslides. The existence of soak pits, which allow water to slowly soak into the ground, is responsible for the creation of cavities between the soil and the boulders. This leads to water seepage and soil erosion, the report said.

The report (1976) also made a few important recommendations to prevent any major disaster as observed recently. The most important preventive measure it suggested was the imposition of restrictions on heavy construction. Construction should only be allowed after examining the load-bearing capacity of the soil and the stability of the site, and restrictions should also be imposed on the excavation of slopes.

The Mishra Committee also advised against cutting trees in the landslide zone and said that extensive plantation work should be undertaken in the area, particularly between Marwari and Joshimath, to conserve soil and water resources. Just over a year-and-a-half before the land subsidence in Joshimath, similar cracks in houses and roads

were reported in June-July 2021, by residents in Raini village, about 22 kilometers from Joshimath town. But no preventive action was taken by the authorities, reports Indian Express.

The Raini village was the birthplace of the famous ‘Chipko Movement’ of the 1970s. Legendary Gaura Devi, who paved the way for the movement, hailed from this Raini village. She played a key role in the Chipko Movement in March 1974 when contractors engaged by an Allahabad-based sports goods company came to Raini village to cut Ash trees. It was Gaura Devi and the women of the nearby villages who hugged the trees and didn’t allow the contractors to cut them, reports NewsClick. The movement got attention across the country and the Central government brought the Forest Protection Act, a law to regulate forests in a bid to conserve them across India. The village of Raini is now a place too dangerous for its residents to live on.

Massive flash floods ravaged Raini village on February 7, 2021, following a glacier coming unstuck and an avalanche in the Alaknanda River. The huge mass of snow, water, boulders, and silt slithered down the Rishiganga River, first damaging the 13 MW private Rishi-Ganga hydropower project and then flowing down to Dhauliganga River to swamp the NTPC-owned 520 MW Tapovan-Vishnugad hydropower project. Again, on June 14, 2021, incessant rains in the region brought back memories of the nightmare. The Rishiganga had swollen due to torrential rains for three days straight, causing soil erosion from underneath the village. This led to big cracks in several houses, instilling fear among the villagers. According to reports, a large portion of the Joshimath-Malari Road beneath Raini village caved in, cutting off around 22 border villages of the Chamoli district.

Suresh Nautiyal, a veteran environmentalist based in Uttarakhand, alleges that consecutive governments have systematically blown away the gains of the Chipko Movement and wilfully aligned with corporations, contractors, industrial companies, and the construction mafia to irretrievably damage the inherent balance of nature. Roads and big dams which displaced thousands, mindless constructions violating all norms, unknown tunnels and aggressive religious tourism have all turned the clock to its current, tragic fate. According to him, the murder of natural streams and rivers, the massacre of trees, the non-stop destruction of the organic eco-system in the relentless race for a capitalist model of unplanned development, blindly copying big cities in the plains, has ravaged the pristine ‘Dev Bhoomi’. Several towns like Gangotri, Uttarkashi, and Gopeshwar are also sinking. Landslides, cloudbursts, and flash floods are inevitable and have become part of the tragic lives of the condemned people of Uttarakhand, reports Lokmarg.

Hydropower projects in Uttarakhand

Referring to the government data (2016), The Wire Science reported that the Uttarakhand government had planned more than 450 hydropower projects, with a total installed capacity of 27,039 MW. At that time, 92 projects with 3,624 MW of installed capacity had been commissioned and 38, with 3,292 MW, were under construction. But the government’s plans were stalled after the Supreme Court intervened following the 2013 floods when over four thousand people drowned. The ministry formed an 11-member body – called EB-I, chaired by Ravi Chopra – in October 2013. This committee’s report stated that hydropower projects had indeed aggravated the impact of the 2013 floods. A “concerned” Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court on December 5, 2014, stating: “any decision on developmental projects especially hydropower projects should … be on very strong and sound footings with scientific back up”.

However, in a drastic change of stance from 2014, the MoEFCC filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court on August 17, 2021, saying a consensus had been reached between the MoEFCC, the power ministry, the Jal Shakti ministry, and the Uttarakhand government to continue work on seven hydropower projects: Tehri II (1,000 MW), Tapovan Vishnugad (520 MW), Vishnugad Pipalkoti (444 MW), Singoli Bhatwari (99 MW), Phata Byung (76 MW), Madmaheshwar (15 MW), and Kaliganga II (4.5 MW)

Of the seven projects that the MoEFCC proposed for construction, five have been damaged in previous flood-related disasters. The 2013 floods damaged Phata Byung, Singoli Bhatwari, Madhmaheshwar, and Kaliganga-II – all in Rudraprayag district. Tapovan Vishnugad, in Chamoli district, was damaged in disasters in 2012, 2013, 2016, and 2021.

The main reason behind the changed stance of MoEFCC was an important policy decision by the PMO. On February 25, 2019, the Union government decided that no new or proposed projects would be considered on the Ganga and its tributaries in Uttarakhand. It also determined that only the seven projects assessed to be “more than 50 per cent complete” could proceed.

In 2021, the MoEFCC argued that the seven projects should go ahead because work on them is more than ‘50 per cent’ complete. But environmentalists were not convinced. On February 7, 2021, a flooded Dhauliganga river damaged

much of the Tapovan Vishnugad project, which was under construction. At least 139 workers were killed at the project site. The MoEFCC affidavit claimed that the project was ‘75 per cent complete’ before the deluge!

As per a report by The Hindu, a group of environmentalists, historians, geologists, and intellectuals have petitioned the Union Environment Ministry to renounce its endorsement of seven hydroelectric power projects (HEP) in Uttarakhand.

Late in October 2022, houses in Joshimath gradually started collapsing due to the cracks, which had been developing for over a year. The Tapovan-Vishnugad Project and the Helang Bypass Project have been blamed for the same. Till last week, the number of houses with cracks stood at 849, out of which 165 are in the ‘unsafe zone’. Only 233 households have been relocated to temporary relief facilities. Apparently, no proper resettlement arrangement has been planned as yet. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court of India (SC) has refused to designate the Joshimath land sinking crisis as a national disaster and declined a plea that sought the SC’s intervention. As per a report by Down To Earth, the court asked the petitioner seeking intervention to approach the Uttarakhand High Court!

Jharia–Ranigunj underground coal fire

In Jharia and Raniganj, large-scale underground fires were detected in the 1970s. These originated from spontaneous combustion occurring due to unscientific coal mining techniques. Those fires have only grown in scale as the government has not been able

to do much about them. Referring to a study made by Coal India Ltd (CIL), the Hindustan Times reported (September 20, 2014) that as per CIL’s assessment, about 37 million tonnes of coal had already been burnt down in Jharia (Jharkhand) and Raniganj (West Bengal) and, if no remedial action was taken., about 1.45 billion tonnes of coal would be burned up, in next few years. More importantly, the lives of hundreds of thousands of people living in these areas would be in danger as parts of the earth’s surface can cave in if the coal-bearing blocks underground burn to

ashes. The then Union Coal and Power Minister Piyush Goyal said the government had planned to shift the population from the underground coal fire-affected areas. The minister agreed that thousands of lives were in danger as they had been staying near the underground fire zone.

It is believed that in a few mines, the fire started over a century ago — in 1916 to be precise. Experts believe that if the coal in these mines could be prevented from burning down and, instead, mined, then India’s coal shortage could be substantially averted. Then why CIL did not take any major initiative to save these mines? The possible reason could be due to the increasing importance the Indian petroleum sector enjoyed since the late

sixties and early seventies of the last century.

After years of deliberations, the government finally approved a master plan, in August 2009, for addressing the issues arising out of these fires. The outlay was: Rs 7,112.11 crore for Jharia and Rs 2,661.73 crore for Raniganj. The timeframe to resolve the issue was ten years. In the absence of any concrete rehabilitation arrangement, thousands of families still live in the areas made vulnerable by unscientific mining. Time magazine reported that

in Jharia alone, 68 fires are burning beneath a 58-square-mile region, showering residents with airborne toxins.

Conclusion

Our planners and policymakers are fully aware of the sensitivity of the mines and mountains. But more powerful voices suppress those sane voices. In a country where the top 1 per cent population owned more than 40.5 per cent of total wealth, in 2021, compared to the bottom 50 per cent (700 million) who owned only around 3 per cent of total wealth, it is inevitable that the State would favour the lobby that controls over forty per cent of the nation’s wealth. In this sad situation, manmade ‘natural disasters’ will keep on occurring in India, maybe at a higher rate!

Views expressed are personal