Economic planning series: Roots of Five-Year Plans

Contrary to the norm in the West where market drove the allocation of resources, India preferred to go with centralised planning even before the independence — laying the groundwork for the borrowed construct of 'Five-Year Plans'

While India's economic development had been driven by Five Year Plans until recently, planning for economic development is not really a universal phenomenon. For instance, the USA does not have five-year plans. Planning does happen but mostly for large-scale projects such as the Tennessee Valley Development, large-scale highway projects or space missions undertaken by NASA. The reason is that the market directs most of the resource allocation in the US while the State has had a far more important role in pushing resources to areas of national priority in India.

The experience of Western Europe also suggests that planning was used to announce annual budgets but not as a tool for long-term economic development. Instead, countries such as France, Sweden, Norway, Britain and Netherlands began an 'outline plan' covering several years in the late 1940s, which was mainly for reconstruction activities in the post-War period. In more recent times, the European Commission has taken up regional plans, which are subject-specific, but the general understanding is that the market should be left alone to direct and allocate resources.

Many developing countries did resort to economic planning after the second World War. Mostly, these were five-year plans and would involve assessing the current state of the economy and investment/expenditure plans for virtually all sectors — from agriculture and industry to transport and energy. Further, these plans generally involved proactive action by the public sector and the various government departments, with the private sector in a supporting role. The overall goal of such planning was to enhance economic growth, reduce poverty and generate jobs, and targets were set for these goals. Many plans used the input-output tables which were introduced as tools by American economists in the early 20th century. The more advanced planning models used programming techniques to arrive at the most efficient allocation of resources.

The Indian experience

Pre-1947 years

Planning, as we understand in India, was an intellectual construct taken from the erstwhile USSR. While planned economic development in India began only in 1951 with the first five-year plan, many economists and thinkers had started putting together a theoretical framework even before independence. In 1934, M Visvesvarya wrote a book 'Planned Economy for India', where he suggested that India should embark on industrialisation so that the surplus labour in agriculture can be absorbed there. He suggested a ten-year plan, at the end of which India's income could be doubled. It may be recalled that the Government of India Act, 1935 had mandated that elections be held to 11 provinces. After the elections were held in 1937, Congress won in most provinces except Punjab and Sind. In 1938, the Industry Ministers of the Congress governments resolved that national planning had to be a tool for industrialisation of the country, which, in turn, would address the problems of poverty and unemployment. Accordingly, the Congress President in 1938, Subash Chandra Bose formed the National Planning Committee under the chairmanship of Jawahar Lal Nehru. Interestingly, this Committee earmarked an important role for the private sector in economic development. It also recommended that coal, defense and public utilities be nationalised and banking be licensed and insurance supervised by a national board. As for agriculture, the Committee recommended collective or cooperative farming as a preferred model.

After this, the World War interfered and India's independence movement became the focus of the Congress. In 1944, a Planning and Development Department, under Sir Ardeshir Dalai, was brought into existence, and simultaneously, the provincial governments were requested to establish their own planning organisations. The years between 1944 and 46 saw the publication of a number of reports: the Kheragat Report on Agricultural Development, the Gadgil Report on Agricultural Credit, the Saraiya Report on Co-operation, the Krishnamachari Report on Agricultural Prices, the Nagpur Report on Roads, the Adarkar Report on Sickness Insurance for Industrial Workers, the Bhore Report on Public Health, the Sergeant Report on Education, and a series of reports on irrigation. However, these reports were disjointed and lacked a unified or national focus. As Vakil and Brahmanand pointed out, the reports "lacked the necessary integration and coordination…they misconceived the nature of the post-War economic situation. The assumptions behind them were those of deflation, falling prices and free availability of Sterling balances. None of them came to pass nor did the govt. visualise that the post-War period would be characterised by an acute imbalance between food needs and internal agricultural production, and that a large portion of its resources would have to be necessarily devoted for purposes of importing food grains."

This led to a flurry of plans and proposals, the prominent among them being the Bombay Plan, the People's Plan and the Gandhian Plan. The Bombay Plan was put forward by a group of industrialists with a total investment of Rs 10,000 crores. It proposed a trebling of national income and doubling of per capita income within a period of 15 years with a focus on industrialisation, especially the production of capital goods.

For addressing the problems of unemployment and inflation, it suggested the fullest use of small-scale and cottage industries.

On the other hand, the People's Plan was the antithesis of the Bombay Plan. It proposed an investment of Rs 15,000 crores spread over 10 years, with an equal focus on agriculture and industry. This plan was proposed by the communist leader MN Roy and had a focus on meeting people's basic needs. While the Bombay Plan was capitalist in nature, the People's Plan proposed an alternative model, with agriculture at its focus.

The Gandhian Plan was more modest. It proposed an investment of Rs 3,500 crores with the basic focus on decentralised planning, and village as a unit of planning. The emphasis was on agriculture and small-scale industry. It laid the foundation of Panchayati Raj which unfolded in the future.

Post-1947 years

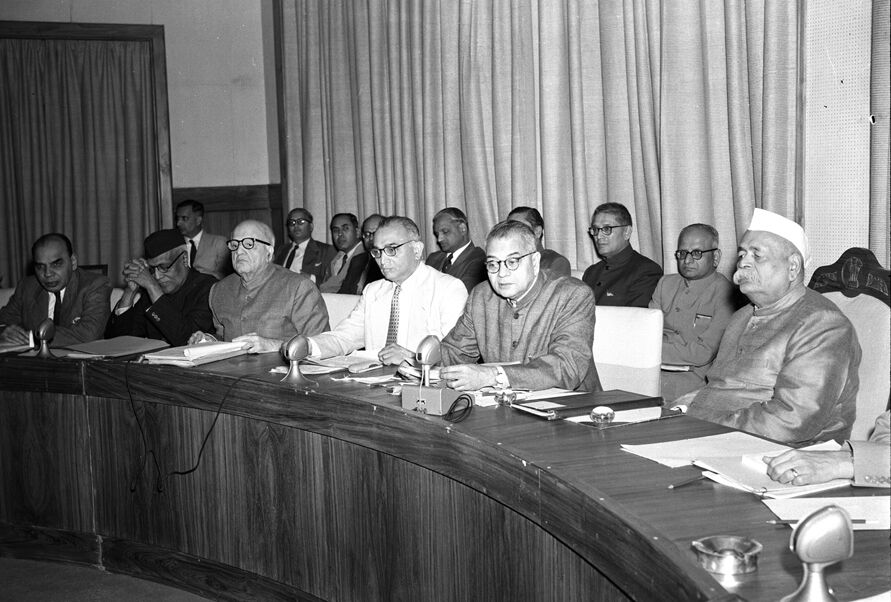

After 1947, the initial years saw various activities such as consolidation of the Constitution and realignment of the government apparatus to the needs of an independent India. As part of these efforts, the Planning Commission was formed on March 15, 1950, with the Prime Minister as its Chairman. The Planning Commission also consisted of a Deputy Chairman of the rank of a cabinet minister and various ministers were co-opted from time to time.

The Indian Planning Commission's functions, as outlined by the Government's 1950 resolution, included assessing the available resources, ensuring balanced utilisation of resources, defining various stages of planning and development and appraisal of various development programmes.

Slowly, the Planning Commission expanded its activities, with the first Five-Year Plan being launched in 1951. The National Development Council (NDC) was formed in 1952 and was tasked mainly with approval of five-year plans. The NDC was also headed by the Prime Minister and consisted of the Central ministries. Another landmark development was the use of a more transparent basis for providing Central assistance. DR Gadgil began working on this when he was the Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission. He noticed that the transfer of Central assistance thus far was not balanced and that poorer states ended up getting lesser grants and more loans as compared to more developed states. This led to the 'Gadgil formula', which divided responsibility between the Planning and Finance Commission and outlined a more fair and transparent mechanism for transferring resources to the states.

After that, there were 12 Plans with each Plan having a focus on one or more sectors. In 2014, a decision was taken to wind down the Planning Commission and replace it with a body called NITI (National Institution for Transforming India) Aayog. The Five-Year Plans were of course inspired by the Five-Year Plans of the Soviet Union, which were first implemented by Joseph Stalin and had a big focus on heavy industries. This was particularly witnessed in the Mahalanobis strategy, which talked of making capital goods through heavy industry and proposed the second Five-Year plan. Many Communist states, including those from Eastern Europe and China, have used Five-Year Plans as instruments of economic development.

Conclusion

India's Five-Year plans borrowed heavily from renowned economists from across the world. This influence was visible from the first Five-Year Plan itself, which relied on the well-known Harrod-Domar model. In. The Five-Year Plans that followed, not only did Indian economists contribute significantly, but India also got the benefit of counsel from leading economists of the world. In this series of articles, which I will call the 'Economic Planning Series', I will trace India's experience with economic planning, beginning with the First-Five Year Plan, the strategies adopted, the theoretical frameworks used and the goals set out and achieved. The broad goals of the Five-Year plans, as we know, were economic growth, regional and balanced development, equity and social justice, poverty eradication, employment generation, self-reliance and modernisation.

The writer is an IAS officer, working as Principal Resident Commissioner, Government of West Bengal. Views expressed are personal