Economic Planning Series: Omnishambles implementation

Based on a ‘flawed logic’, and interspersed with two wars and a drought, the third plan — relying heavily on heavy industries and import substitution — not just missed its core targets with huge margins but also pushed India into ‘export pessimism’

In the first part of the article on the Third Five-Year plan, we discussed the key features of the plan. In this concluding article, we shall delve deeper into the distribution of financial outlays across various sectors, and present a critical assessment of the plan.

Financial outlay

To raise national income by more than five per cent per annum, and to increase the net investment ratio from the then 11 per cent to 14-15 per cent by the end of the plan period, the national income would need to rise from Rs 14,500 crore (at 1960–61 prices) to Rs 19,000 crore. Hence, the national income was to rise by 30 per cent and per capita income by 17 per cent. Accordingly, the plan proposed an outlay of Rs 7,500 crore in the public sector. Of this, Rs 6,300 crore represented investment and Rs 1,200 crore represented expenditure on staff and subsidies among other things. Investment by the private sector was estimated at Rs 4,100 crore, thus making a total investment of Rs 10,400 crore during the five-year period. Actual expenditure in the public sector, however, amounted to Rs 8,576.5 crore. Transport and communications continued to get a lion's share of the allotment with nearly 1/4th of the outlay. Industry, including village and small industries, came second with 23 per cent of the actual outlay, followed by agriculture, including irrigation and community development with 20.4 per cent of the outlay. Percentage expenditure on social services remained more or less the same at 17.3 per cent in the Third Five-Year Plan as against 18 per cent in the second.

Of Rs 8,577 crore of public expenditure, Rs 5,012 (58 per cent) came from domestic budgetary sources; Rs 2,433 crore (28.2 per cent) through external assistance; the balance of Rs 1,133 crore (13.3 per cent) was raised through deficit financing. This amount was double of that originally provided, although the share declined from 26.4 per cent of the total public expenditure in the First Five-Year Plan to 13.3 per cent in the third plan. This worsened the inflationary situation which had already developed in the country.

Total revenue receipts of the Centre, the states and Union territories rose by 100 per cent. The yield from additional taxation exceeded the target of Rs 1,710 crore by Rs 1,182 crore. However, a bulk of the revenue went to finance non-plan expenditures including defence, emoluments and allowances of government servants.

The third plan was to be supplemented by substantial external assistance including the food aid PL 480, which was to come from the USA.

Critical assessment

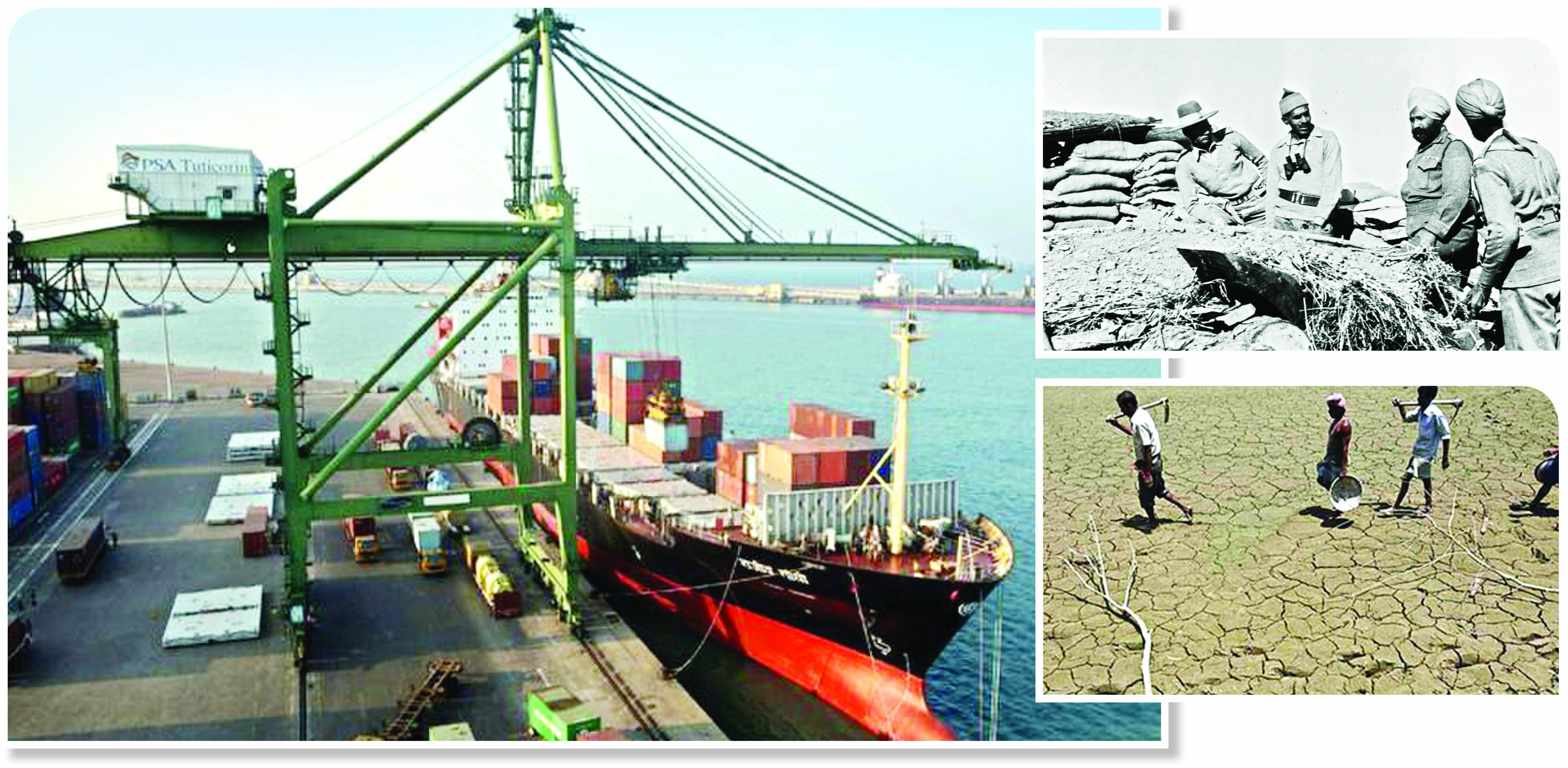

As it turned out, the third plan faced problems from the start, beginning with the war with China in 1962, and later with Pakistan in 1965. On top of that, the monsoons failed in 1965, leading to a lower-than-expected agricultural harvest. Consequently, targets were missed and various sectors such as agriculture, irrigation, power and industry saw shortfalls. From agricultural goods such as food grains and oil seeds to industrial production of steel and cement, everything fell short of targets. The high levels of deficit financing led to inflationary pressures, which made matters worse. Further, the rise in non-plan expenditure crowded out investment expenditure by the government.

As noted above, on the employment front too, the plan fared badly. Against an estimated 25 million unemployed persons in the country, the third plan could create only 14 million additional jobs. Thus, the number of the unemployed at the end of the plan was greater than at the beginning.

The objective of reducing inequality remained on paper, and the social structure remained largely intact, which often became a hurdle for growth. Apart from the abolition of the zamindari system, very little was done in this regard.

On the industry front, the third plan relied even more on heavy industry than the second plan. Since success in industry was dependent on regular supply of materials and steady supply of power, and this didn't go as planned, there were shortfalls. From 1963 onwards, there was a shortage of coal, power, steel and transport. In fact, India had to resort to imports of steel, since the steel plants were still expanding. Industrial growth therefore fell short of the targets, growing on average at around seven per cent as compared to the target of 14 per cent.

In agriculture, the emphasis was on quick yielding varieties, but the dependence on monsoons continued. Further, the planned expansion of fertilizer capacity was not realized. Agricultural production fell to 72 million tonnes from the second plan achievement of 82 million tonnes because of a shortfall in monsoons.

There was much emphasis on maintaining stable prices, and the third plan sought to use monetary and fiscal policies in this direction. Fiscal policy was to mop up the excess purchasing power, and thus to restrain consumption; fiscal and monetary disciplines also targeted the limiting of deficit financing and restraining the secondary expansion of money, following the primary expansion of government money. Monetary policy was to restrain excessive credit expansion while, at the same time, meeting the genuine credit needs of the economy. For food grains, there were physical controls in place, which included open market operations and procurement of food grains to sell them at cheap prices from government ration shops. As it turned out, these efforts didn't succeed completely, and the economy faced high inflation levels including high food prices.

The mobilization of external resources was critical for financing the plan. This was because the balance of payments was expected to be in the red. Of the total balance of payments gap of Rs 32 billion, Rs six billion was on account of PL 480 imports, Rs 19 billion was in respect of projects included in the Plan and Rs seven billion was non-project assistance needed over the five years. In other words, India was relying on external aid from the World Bank and countries such as the USA, the USSR and the UK. As it turned out, a large gap in external aid remained. On top of that, imports outstripped exports. In fact, the weight of the external sector in the GDP declined from the first two plans. In 1951, exports plus imports accounted for 15.8 per cent of the GDP. BY 1965, this figure had fallen to 7.7 per cent. This was mostly because of the inward-looking import substitution policy pursued, which led to the export basket being limited to tea, jute and cotton textiles for a long time — areas where there was little scope of expansion in world trade. Consequently, the current account deficit also came under heavy pressure.

As a result of the adverse balance of payments and current account deficit, the demands of the wars with China and Pakistan and a contraction of aid, the rupee came under pressure. India was left with no other option but to devalue the rupee by 36.5 per cent in 1966.

However, this dismal situation can't be seen in isolation and was a result of the disproportionate focus on import substitution and heavy industry. The intention, however, was noble, and it was thought that investment in heavy industries would bring in savings in foreign exchange as output from such industries would replace their imports in the long-run. Import-substituting strategies were expected to gradually increase export competitiveness through efficiency gains achieved in the domestic economy. However, as we know, the logic was faulty and India became locked into this 'export pessimism' mindset, even as other countries such as South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan were moving strongly in the opposite direction with an emphasis on exports. Because of a relatively closed economy, Indian industry also remained uncompetitive, which worsened steadily as more and more controls were put in place.

Conclusion

On the whole, the third plan did not live up to the expectations and could not achieve the objectives which were set. While there was some success in mining, engineering industries such as automobiles and capital goods such as textile machinery, engines and transformers, the plan could not meet its targets in agriculture and industrial production. Further, faced with two wars and a drought in 1965 and an adverse balance of payments situation, the government was forced to go in for a devaluation of the rupee. It was because of the overall failure of the third plan that the Government of India declared a plan holiday at the end of the third plan. Consequently, there was no five-year plan for three years. We will discuss this in the next article.

The writer is an IAS officer, working as Pr. Secretary, Technical Education, Training & Skill Development, Government of West Bengal. Views expressed are personal