Eastward but Unequal

As Asia-Pacific economies deepen their trade web through RCEP, India’s absence grows costlier — widening deficits, missed opportunities, and a faltering ‘Look East’ vision

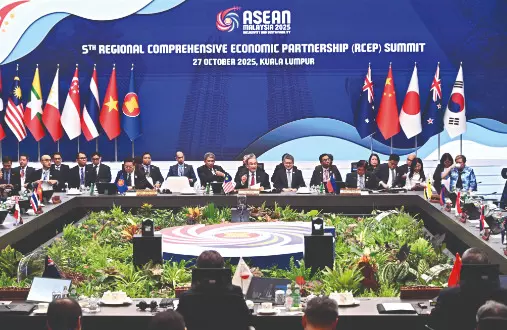

On October 27, 2025, Malaysia hosted the 5th Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Summit in Kuala Lumpur, together with Leaders of the RCEP Participating Countries, namely ASEAN Member States, Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and the Republic of Korea. This was the first Leaders’ meeting since the RCEP Agreement entered into force in 2022, and the first since the signing Ceremony at the 4th RCEP Summit on November 15, 2020. RCEP, the world’s largest free trade bloc, brings together 15 Asia-Pacific nations, encompassing about 30 per cent of global gross domestic product — equivalent to USD 25.9 trillion and a third of the world population. The pact aims to deepen regional economic integration, streamline trade, and strengthen supply chains. Recently, four developing nations- Hong Kong, Sri Lanka, Chile, and Bangladesh have submitted their formal application for RCEP membership. The 5th RCEP summit received added attention due to the ongoing tariff war initiated by US President Donald Trump.

Based on the AGI RCEP Trade Tracker, a report prepared by the Asian Global Institute has compiled a comparative analysis of trade performance from Q1 2020 to Q3 2024, ensuring a consistent comparison of trade trends across years. The analysis reveals several critical trends shaping RCEP’s trade dynamics:

* China remains the dominant exporter within RCEP, with total exports to its regional partners reaching USD 2.76 billion in Q1–Q3 2024. The 3.6 per cent increase in 2024 marks a cautious recovery after an 8.5 per cent increase in the year before. While the downturn in 2023 reflected global economic uncertainties and shifting supply chains, the modest rebound in 2024 suggests that China’s trade with RCEP is stabilising.

* Japan’s trade relations with RCEP countries have undergone a notable transformation since 2020, characterised by fluctuating patterns of substantial growth and significant declines. After a remarkable 23.2 per cent surge in Japan’s exports to RCEP countries in 2021, the momentum quickly faded. By 2023, total exports had plunged by 13.3 per cent, and the downward trend continued in 2024 with a 3.5 per cent contraction, which suggests a cooling down of demand.

* Intra-ASEAN trade has shown significant fluctuations over the years, with strong growth in 2021 and 2022, followed by a contraction in 2023, and a moderate recovery in 2024. In 2023, intra-ASEAN trade declined by 13.3 per cent, mirroring a slowdown in global trade, supply chain disruptions, and possibly weaker domestic demand in key ASEAN economies. Despite this setback, 2024 showed signs of stabilisation, with intra-ASEAN trade increasing by 7.03 per cent, signalling a cautious recovery.

* Trade between RCEP members and non-member nations has exhibited a dynamic trajectory, featuring significant growth alongside occasional periods of deceleration. In the first three quarters of 2024, trade between RCEP countries and partners outside the bloc rose to USD 3.37 trillion, representing a 5 per cent increase from 2023. The most significant growth occurred in 2021, with trade surging by almost 30 per cent due to post-pandemic recovery and robust global demand. However, this momentum was briefly interrupted in 2023, as exports to non-RCEP partners declined by 7 per cent, a reflection of global economic headwinds and tightening financial conditions. Despite this setback, 2024 marked a strong rebound, underscoring the resilience and adaptability of RCEP economies as they continue to strengthen their global trade networks. South Korea has been a leading force in this expansion, with its exports to non-RCEP partners climbing to USD 289 billion in 2024.

The joint statement of the RCEP leaders issued at the 5th Summit reaffirmed their commitment to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules and principles as the foundations of an open, transparent, fair and rules-based multilateral trading system that ensures predictability and non-discrimination for all trading partners. They underscored that regional integration pursued within the framework of the multilateral trading system, with the WTO at its core, is fundamental to the region’s economic stability, resilience and long-term prosperity, and highlighted the importance of ambitious WTO reform to ensure the organisation better deliver on the interests of all Members. Significantly, in September 2025, China announced that it would not seek new special and differential treatment (SDT) in current and future negotiations at the World Trade Organisation (WTO). This announcement has boosted the Chinese image among the developed countries as the leader of the global south.

Bangladesh’s membership in RCEP will be a major game-changer in the South Asian region. Trade analysts argue that in Bangladesh, services exports have grown rapidly but remain narrow in scope and are overshadowed by rising imports, leading to persistent deficits. RCEP countries account for a substantial share of Bangladesh’s services trade. Accession to RCEP could help secure reciprocal market access and offset the loss of LDC trade preferences after 2026, but it will require targeted reforms to liberalise investment regimes, close regulatory gaps, and align domestic policies with RCEP commitments.

India had pulled out of the RCEP in 2019 due to concerns of Chinese goods flooding Indian markets. India’s trade deficit with RCEP countries was over USD 100 billion in 2019, half of which was with China. After five years, in 2024-25, India’s trade deficit with RCEP Member nations has increased to USD 179.2 billion. The trade deficit with China reached USD 99.25 billion. Several ASEAN countries with which India shares close relations had expressed their disappointment pertaining to India’s pull-out from RCEP. Japan has also been pushing for India’s entry into the RCEP. Recently, Chinese expert Liqing Zhang, director of the Centre for International Finance Studies in Beijing, stated that China could import more from India if New Delhi joins the RCEP and becomes more open to Beijing. He emphasised RCEP’s potential to enhance the competitiveness of Indian goods and bilateral trade, urging India to reconsider its stance. The tariffs on manufactured goods within RCEP are set to fall to zero within a decade.

Trade data indicate India has strong reasons to be sceptical about its prospects with RCEP. India suffers from a severe trade deficit with members of RCEP, except New Zealand, with which it has a marginal trade surplus. Trade deficits with ASEAN, South Korea, and Japan, with whom India has enjoyed free trade agreements for over a decade, are also substantial. India imports nearly 25 per cent of its total imports, and exports less than 10 per cent of its total exports from/to the RCEP bloc. India’s trade deficit with RCEP (USD 179.2 billion) is nearly double the total trade deficit of USD 94.41 billion in 2024-25 and is higher than the trade deficit with China at USD 99.25 billion.

It appears that India has miserably failed in managing its ‘Look East Policy’. If no corrective measures are taken at the earliest, cheap imports from East Asian countries will destroy India’s local producers, who are still fighting an unequal competition with their limited resources and basic technology.

Views expressed are personal. The writer is a professor of Business Administration who primarily writes on political economy, global trade, and sustainable development