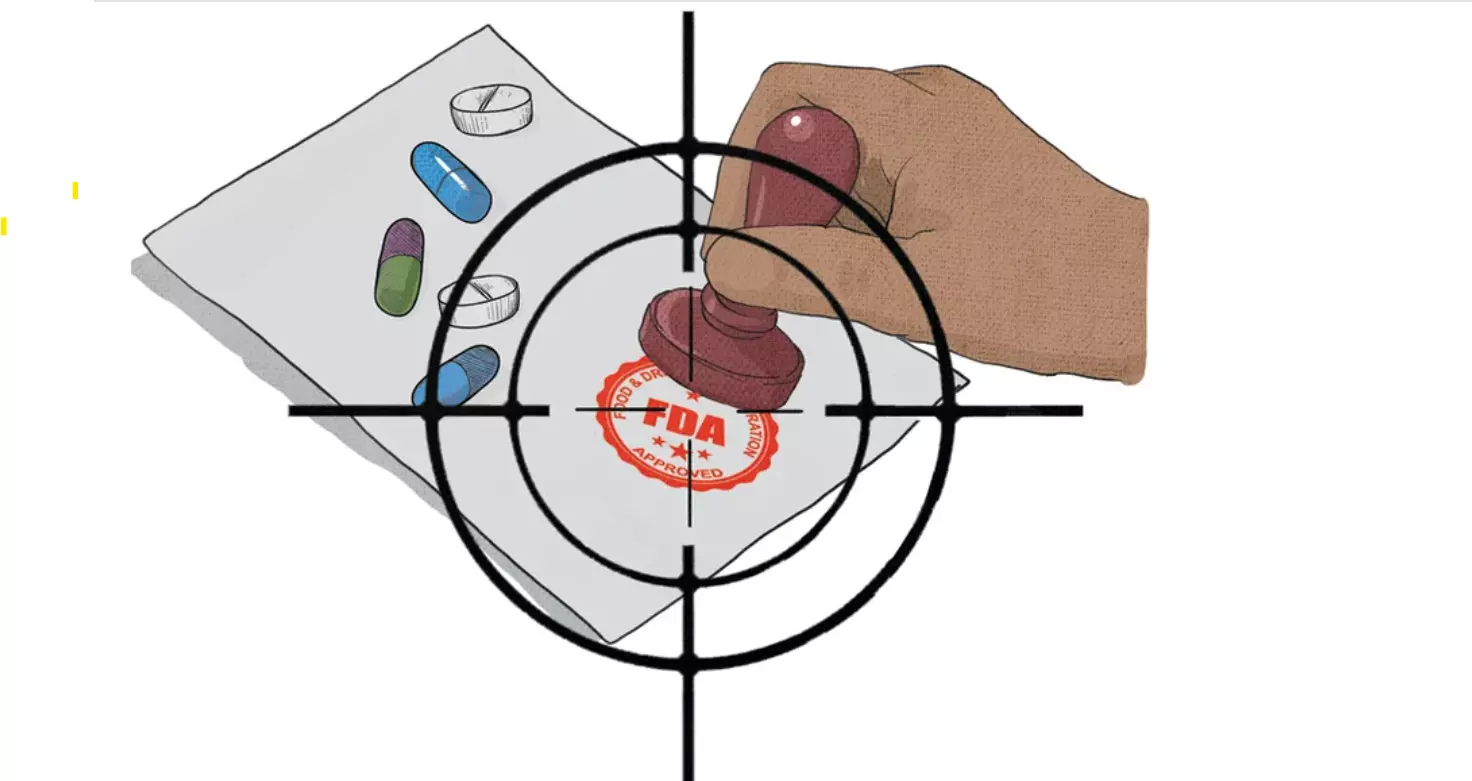

A perilous pursuit

Trump's aide Vivek Ramaswamy has a risky agenda on his side; he wants to gut the Food and Drug Administration to make drug approvals easy and quick

Failed Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy is making more news now than during his doomed attempt to get the party nomination for president. Ramaswamy’s decision to throw in the towel and back Donald Trump after his campaign went nowhere showed acumen, the kind he is famous for in the investment world. The president-elect has appointed the Indian-origin pharma investor, along with Elon Musk, as the head of an initiative to slash the federal bureaucracy. For Ramaswamy, heading the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is the perfect reward: he does not like federal agencies and wants to shut down the Department of Education and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and drastically restructure the Federal Reserve. But his main target is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the federal pharmaceutical regulator which has been in his cross hairs since the time he set up his drug manufacturing company Roivant Sciences and its much-hyped drug failed to make the cut.

The story of Ramaswamy and his visceral antipathy to FDA is tied up with his business approach to pharma manufacture. He is given to projecting himself as a scientist from the biotechnology sphere, although he is no scientist, and has just an undergraduate degree in biology. His graduate degree is in law and he started his career with a hedge fund company where he specialised in biotech investments. That appears to have fuelled the idea of setting up his own pharma ventures. His model was simple: scour the patent web for drugs that had been abandoned by pharma majors, buy out the patents—these could be had for a song—and develop and bring them to market to make a killing. The model was very much that of Martin Shkreli’s.

Shkreli was also a hedge fund manager who co-founded drug companies Retrophin and Turing Pharmaceuticals and became notorious for his rapacious pricing of pyrimethamine, a drug to treat parasitic infections. Shkreli had bought the rights to the drug at a throwaway price and hiked its price by 5,000 per cent. Business-savvy Ramaswamy did something similar but took on more risk by hyping a drug that was yet to be approved. He bought the patent rights to Intepirdine, an experimental drug abandoned by GSK (GlaxoSmithKline) after the final clinical trials failed, for just US $5 million in 2015. It was bought through Roivant, but Intepiridine was parcelled out to Axovant, a Roivant subsidiary. In the biotech industry, which thrives on speculation and the promise of big returns, Ramaswamy was able to garner the largest initial public offering in the industry’s history for Axovant. Intepiridine failed and Axovant’s share value crashed, but before that, its promoter had cashed out. And he made another pile by selling promising parts of Axovant to a Japanese corporation.

On the political campaign trail in the past two years, he has been scathing in its attack on federal regulatory bodies, from the Environment Protection Agency (EPA) to FDA and everything else in between. Musk and Ramaswamy believe slashing budgets and reducing human resources by 75 per cent will ensure that businesses will be allowed to operate more freely and more profitably. Their own businesses in particular. If FDA rules on clinical trials have a bearing on Ramaswamy’s company, Musk’s electric vehicles company Tesla has run afoul of EPA regulations.

What is the pharma entrepreneur’s gripe with FDA? After all, the agency has approved at least six of Roivant’s drugs and helped boost its market capitalisation to $9 billion. Some pharma insiders have pointed out that Ramaswamy’s attacks on FDA are hypocritical and dangerous, to say the least, since his $1-billion personal fortune came on the back of approvals by FDA. Others have emphasised the importance of safety provided by the regulatory agency. Even then, medicines have proven dangerous, such as Merck’s painkiller Vioxx that had to be pulled out for causing heart attacks. Harmful medicines would continue to be in the market if a regulator were not keeping tabs on developments. The most cited case is that of thalidomide, which caused dangerous birth defects in children whose mothers had taken the medicine for controlling nausea during their pregnancy. It goes to the credit of FDA that it steadfastly refused to approve thalidomide for morning sickness even though it was sold in other developed countries. Richardson-Merrell, the company marketing it in the US, sought FDA approval six times and was refused each time. The thalidomide case prompted Congress to instruct FDA to ensure that manufacturers demonstrate both the safety and effectiveness of their drugs.

Many of the rules laid down by FDA could be viewed as laborious and time-consuming, but they keep these two precepts in mind when seeking a replication of clinical trials. The simple reason is to make sure people are not buying unproven and ineffective medicines—as Roivant’s Intepiridine might have been without the full range of testing. Ramaswamy, however, accuses the agency of corruption and unnecessarily adding to the costs of drug developments through its requirements. In a recent post on X (formerly Twitter), he said his main concern is that FDA “erects unnecessary barriers to innovation” by asking for two Phase-3 studies instead of one and refusing to accept valid clinical results from other nations, among other measures. He contends that this stops patients from accessing “promising therapies” and raises drug costs by impeding competition.

He also accuses the FDA staff of having “callous disregard for the impact of their daily decisions on the cost of developing new therapies, which inevitably gets passed on to the healthcare system”. What he conveniently ignores in this broadside is that FDA has no role in pricing of drugs: the big manufacturers decide on this by making their own calculations on what it cost them to acquire new technologies and promising therapies from small biotech companies actually focused on drug discovery.

The real problem of drug pricing does not appear to interest the Roivant promoter, and why should it? The “Roi” in the company’s name stands for “return on investment”, and Ramaswamy has been forthright about his chief aim in setting up the company. In an interview to Forbes, he declared: “This will be the highest return on investment endeavour ever taken up in the pharmaceutical industry.” How better than to be allowed untrammelled manufacture of drugs? Drug makers across the world who are subject to FDA rules for the export and marketing of medicines to the American market, not least Indian generics companies, are holding their breath to see what Ramaswamy’s DOGE does to the regulator. DTE

Views expressed are personal