When Cinema Pauses, Gandhi Enters

A look at how cinema has engaged with Gandhi through tone, hesitation and presence

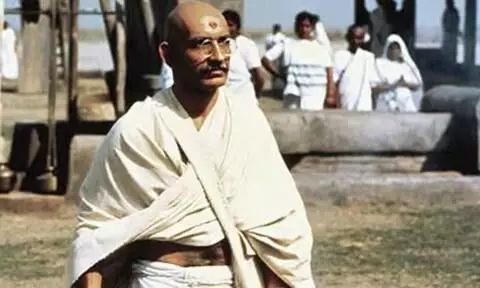

Gandhi (1982), directed by Richard Attenborough

Every Indian grows up with Gandhi as a presence. He exists in photographs, in classrooms, on currency notes and in the larger public memory. Cinema, too, has never entirely let go of him. What has changed isn’t Gandhi himself, but the way films choose to sit with him.

Gandhi is one of the few figures in cinema who seems to change simply by walking into a different space. His idea doesn't alter, but the room around him does. The moment you place Gandhi in Hollywood, Hindi cinema or regional films, his body language shifts and so does ours.

In Richard Attenborough’s ‘Gandhi’, the world seems to slow down in his presence. The camera lingers. Silence is allowed to stretch. His white clothes blend into the light, as if he belongs as much to the frame as to history itself. This portrayal reflects a time when complexity could wait, but moral clarity could not. Cinema and perhaps the nation itself needed Gandhi to remain intact.

That clarity begins to strain in ‘Sardar’, where Gandhian idealism meets Vallabhbhai Patel’s administrative urgency. The film doesn’t dismantle Gandhi’s authority, but it allows tension to exist. Cinema here admits something quietly uncomfortable that moral conviction and political necessity do not always move at the same pace.

The tension sharpens further in ‘The Legend of Bhagat Singh’. He matters, but the camera follows urgency elsewhere. Anger and sacrifice dominate the frame. There is an unspoken negotiation at work. The film refuses to slow down, even as it doesn’t reject Gandhi.

Then comes ‘Lage Raho Munna Bhai’, one of Hindi cinema’s most emotionally intimate engagements with Gandhi, which does something radical in its gentleness. It turns Gandhi into a companion rather than a commander. He appears as a guide during moments of confusion and steps aside before things turn morally messy. ‘Ajab Prem Ki Ghazab Kahani’ portrays Gandhi as familiar enough to joke about, yet gentle enough to keep the narrative flow uninterrupted.

Regional cinema often appears more at ease with him. In ‘Hey Ram’, Gandhi is neither a pedestal nor comfort. The assassination isn’t treated as distant history, but as a psychological rupture. The narrative doesn’t explain the violence. It sits with it.

Marathi films like ‘Dr. Prakash Baba Amte: The Real Hero’ treats Gandhian ethics as a lived discipline rather than a declaration. Bengali cinema, notably Satyajit Ray’s ‘Ghare-Baire’, trusts the audience with complexity rather than consensus.

Today, Gandhi enters films not through physical presence but through tonal shift. You recognise the moment he arrives, even when he is unseen. It isn’t inspiration or guilt. It’s something quieter or even slightly awkward, like when a respected elder walks into a room and the conversation automatically changes.

Indian cinema has carried this feeling for decades. He keeps returning not as agreement or instruction, but as an interruption. Sometimes he slows the room down. Sometimes he unsettles it. Often, he lingers just outside the frame, felt more than seen.

Gandhi doesn’t ask cinema to follow him. He asks it to pause. And cinema, like society, keeps deciding how much of that pause it can afford.

Darshim Saxena writes on cinema and culture