The 'musical universe'

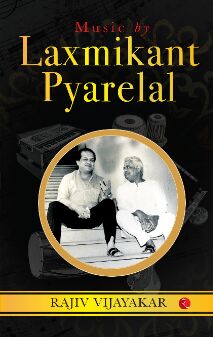

Rajiv Vijayakar’s Music by Laxmikant Pyarelal takes us through the three-decade long melodious journey of the duo that reigned supreme all throughout in the changing kaleidoscope of music industry through their profound versatility and unmatched quality; Excerpts:

Laxmikant, unlike all other film composers, would never play the harmonium, but only keep his fingers pressed continuously on Sa (the first note) and Pa (the fifth note) while he ruminated on a tune, and even when the song emerged and he was singing it. Musicologist, performer, music author and lecturer Deepak Raja shed light on this mystery and unveiled one of the biggest secrets of the success of Laxmikant-Pyarelal.

'It is common practice in the popular music industry for composers to use the standard harmonium or keyboard for the purpose of composing, and also for imparting their compositions to singers and musicians. The harmonium has a 12-note scale. So, by implication, the composer has limited melodic imagination to those 12 standard notes. But this can be a pragmatic approach because it makes the sharing of melodic patterns between the composer, the singers and the musicians almost effortless,' said Raja.

But Laxmikant was different. He used only the Sa-Pa notes on the harmonium when he composed, and also when he was sharing the composition with singers. And for this, the musicologist has a fascinating explanation: 'Sa-Pa is the standard tuning of the tanpura, because the first and fifth notes are the pivotal notes of the scale, which are achal or fixed. Evidently, then, the harmonium was used by Laxmikant as a substitute for a tanpura. By the principle of harmonics (sound frequencies resonating to the fundamental), the tanpura creates a spectrum of sound, within which the musician can freely access any of the 22 notes (shrutis) constituting the Indian music scale.'

He went on, 'Sa-Pa on the harmonium may not give the acoustic richness of a tanpura. But it will certainly free the melodic imagination from the limitations of the 12-note scale of the harmonium. The composer can then hear all the 22 notes or shrutis in his ear while doing this, and can be said to be in some kind of a subliminal trance, from which he can come out with melodies that can be more complex, even for the singer! Sa and Pa allow you to focus on the entire spectrum of the sound and scale rather than on any particular note. Creative abilities are triggered off in multiple layers and you can focus on them and not be stuck on any particular pitch.'

Little wonder then that Laxmikant-Pyarelal's music makes music lovers go on a different kind of trip!

As we have seen so far, the understanding between Laxmikant and Pyarelal was nothing short of miraculous. In the final analysis, these two disparate individuals from completely contrasting backgrounds came to a common goal when work was concerned. Said Pyarelal, 'My thirst for knowledge was so intense that I would just observe great musicians when I got a chance, and when we struck up a friendship with Hridaynath (Mangeshkar), I would sit in a corner of their house and quietly observe and listen to the great luminaries who visited the Mangeshkars—Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Abdul Karim Khan, Dagar Brothers and the greats from Marathi natyasangeet (music for Marathi musical plays, a genre in itself). Laxmi would be with me and we would just try to know why music was what it was, like how natyasangeet would also have a strong classical base and yet sound so simple and melodious. As a composer in cinema, you have to compose classical, jazz, pop, cabaret, a ghazal, a thumri, a qawwali, a bhajan, folk, a children's song and so much more.'

He added, 'In films, you have to think both ways. On the one hand, Anand Bakshi's superb poetry in "Khat Likh De Saawariya Ke Naam Babu" (Aaye Din Bahaar Ke) or Sahir's "Yeh Dil Tum Bin" (Izzat) were both written first. But on the other, even when a song is written to a tune, the thought is already there. While working, your mind has to be open and active. We have seen how the Shagird song "Dil Vil Pyar Vyar" was an example of this. Let me give you another example. Shashi Kapoor and we had a lot of mutual affection right from the Jab Jab Phool Khile days when we worked with Kalyanji-Anandji. He suggested that we should try and make a song on the Indian musical sargam. The result was "Sa Re Ga Ma Pa", the hit song from Abhinetri that was filmed on Hema Malini and him.

Let us take the song "Ek Do Teen Char" from Tezaab. It is a tune sung by Mumbai's rama-log (groups of young domestic servants) when they are celebrating some occasion. Laxmi loved it and made Javed Akhtar listen to it. And Javed said, "I feel that two people in love will think of how much one waits for the other, so we should use numbers from ek (one) onwards." The prelude ended with the numbers going up to terah (13). This was linked to the mukhda that actually began with "Tera karoon din gin gin ke intezaar (I am counting the days as I wait for you)" with a pun on the successive 'terah' and 'tera'. This was the thought, the mood. People accused us of copying the basic tune, but it is all team work—choreographer Saroj Khan and director N. Chandra also did their bit and the final song can be called our song and was a chartbuster.'

Pyarelal continued with their story of camaraderie, 'Laxmi and I firmly believed that while working, the egoistic word 'Main' (I) never interferes. Every song is teamwork, and for us, it was a great shouq (passion) too. A song like 'Dafliwale' (Sargam) is not only about our work and how we used 18 daffs (a handheld percussion instrument) when Rishi Kapoor is playing one on screen. It is also about the director's choice of our composition and musical treatment, his vision for the song within the film, the dance director's work, and the expertise of the director of photography, the actor, actress and dancers in a dance number, and also the film's editor. Last but not least, it's about the public that makes it work! Why? Because yeh public hai yeh sab jaanti hai (The public knows best)!' And Pyarelal chuckled as he quoted their hit song in Roti.

Another frequent Laxmikant-Pyarelal touch was of many songs having differently composed antaras. 'We loved to do that!' affirmed Pyarelal. 'Naushad saab and a few others had this habit, and we picked it up from them.'

How do they decide the orchestration and the ratio of Indian to Western instruments? 'That's very simple. When you go out, you wear clothes as per the occasion: a casual stroll, a formal occasion, meeting a dear friend and so on. In music too, it is the same. What is the song, what kind and for whom? It is the same with raags or with Western music. Taal, bandish, sur—we as composers must know all about them.' Citing their climax song of Karz, Pyarelal said, 'The high-pitched and soaring notes at the end of the mukhda of "Ek Hasina Thi" (Karz) are to evoke the feeling of the past vis-à-vis the present, and this kind of musical high thinking has to be cultivated. Then we have to think of the interludes and their mood—here the music piece that my brother Gorakh played for us has become iconic. Music is there in everything, and the way we talk and think is all swar (voice). Our thinking has to be multi-dimensional.'

(Excerpted with permission from Rajiv Vijayakar's Music by Laxmikant Pyar; published by Rupa Publications)