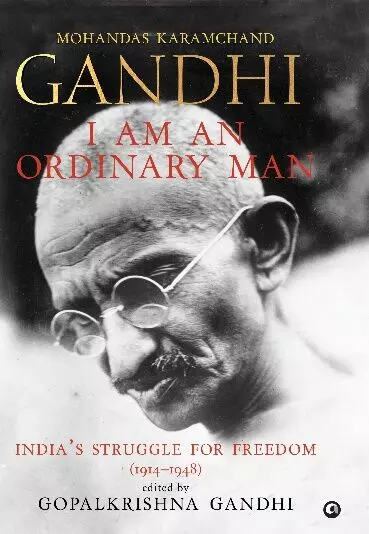

The man behind the legend

‘I Am an Ordinary Man’, edited by Gopalkrishna Gandhi, takes readers on a journey through Mahatma’s life after he returned to India in 1914 — narrating in his own words his political philosophies, convictions, doubts, and determinations, as well as personal struggles he embraced in pursuit of India’s independence

With Linlithgow gone and Wavell installed in his place, the political prospects for India are once again uncertain.

Gandhi, in jail, loses his life companion on 22 February. ‘We were a couple outside the ordinary,’ he writes to Lord Wavell who has condoled the death. Gandhi sees and says that the way her illness and death were handled by the Raj lacked grace.

In May, he is released. The government can take no chances with his health which has been enfeebled. But it does not bend an inch when it comes to negotiation. It will hear of no truce unless Quit India is rescinded. That is not in Gandhi’s or anyone’s powers to do.

Rajaji’s ‘formula’ for an entente between the Muslim League and the Raj is accepted by Gandhi as a possibility for exploration with Jinnah. The two have several rounds of talks in Bombay, in vain.

Towards the end of the year, Gandhi has another health setback.

Her condition worsened on 4 January. On 6 January, I wrote to the superintendent conveying her wish for Kanu Gandhi, Narandas’s son, to visit her for about an hour daily so that he can sing her some bhajans and also do some little nursing.… If some relations can see the patient once a week, it would give her some mental peace. ‘I must confess,’ I wrote, ‘that the patient has got into very low spirits. She despairs of life and is looking forward to death to deliver her. If she rallies on one day, more often than not, she is worse on the next. Her state is pitiful.’ I also said Smt Prabhavati Jayaprakash Narayan has done a lot of nursing of the patient before. She is like a daughter to us. If she is sent, she will be of great help.

I took ill on 18 January and took some sarpagandha, an Ayurvedic preparation, but adjusting it against the regulated intake of only five substances in my food, dropped one. On 27 January, I wrote to the government saying in the facilities being allowed to the patient grace has been sadly lacking. I said my three sons are in Poona. ‘The eldest, Harilal,’ I wrote, ‘was not allowed yesterday, the reason being that the IGP had no instructions to allow him to come again. And yet the patient was naturally anxious to meet him….’ Not getting a reply to that letter, I wrote again on 31 January: I hope it may not have to be said that relief came too late.

Vijayalakshmi had written conveying the news of her husband Ranjit’s death on 14 January. I wrote to her that when I read out the news to Ba, she said with tears in her eyes: ‘Oh Rama, I am at death’s door,

and I am not taken away while Ranjit is taken away! What will happen to Sarup?’ This was my first letter from jail. It was to be delivered against the rules, even as her incoming was the first to be delivered to me.

Ba asked me on 2 February, with some impatience, as to what was happening about the nature cure expert coming to see her. ‘I am at it,’ I said, ‘but we are prisoners, aren’t we?’ When a nature cure expert was allowed to visit and examine her, it was with the condition that no one else would be present in the room. It is unbecoming of government, I wrote to the authorities, to impose such a condition. Supposing she needed a bedpan when Dr Dinshaw Mehta is there, who is to give it to her if the nurses are not to be near her? Suppose I want to ask the nature cure doctor how my wife is progressing, am I to do so through someone else? This is a curious situation. I would far rather the government sent me away to another prison instead of worrying me with pinpricks at every step. If I am away, I said, my wife would not expect any help from me, and I will be spared the agony of being a helpless witness to her suffering.

Vaidyaraj Shri Shiv Sharma was permitted to attend on her. When he started his treatment, I suspended the treatment that Drs Gilder and Sushila were giving her. But there were many limitations placed on the vaidyaraj’s daily visits, with the result that he very kindly agreed to sleep in his car just outside the camp and come in whenever and at whatever time he was needed. On 16 February, I wrote to the IG of prisons: ‘I am writing this by the patient’s bedside at 2 a.m. She is oscillating between life and death. Needless to say, she knows nothing of this letter. She is now hardly able to judge for herself.’ I asked for the vaidyaraj to be permitted to remain in the camp, day and night. If the government cannot agree to this, to release the patient on parole to receive the full benefit of the physician’s treatment. And if neither of the two proposals are acceptable, to remove me to any other place of detention. ‘I must not be made a helpless witness to the agonies the patient is passing through.’

Harilal came on 17 and 18 February to see Ba.

On 18 February, I asked the vaidyaraj, who had been most assiduous and attentive, to cease his treatment because he would not continue it when his last prescription failed to bring about the result he had expected. And I asked Drs Gilder and Nayar to resume the suspended treatment. By 21 February, her condition was grave. Devadas wanted a chance to be given to penicillin. I said to him he must not try to drug her on her deathbed and now, at this moment, just trust God. Harilal came. He was under the influence of liquor.

On the evening of 22 February, I was called by her. I took over from those who were giving her restful support. I leaned her against my shoulder and tried to give her what comfort I could. All present— some ten of them—stood in front. She moved her arms for fuller comfort. Then, in the twinkling of an eye, with Harilal, Ramdas, and Devadas also beside her, the end came. It was 7.35 p.m. By the Hindu calendar, Shivaratri.

The IG of prisons took down in writing to my dictation at 8.07 p.m. the following:

1. Body should be handed over to my sons and relatives which should mean a public funeral without interference from government.

2. If that is not possible, funeral should take place as in the case of Mahadev Desai; and if the government will allow relatives only to be present at the funeral, I shall not be able to accept the privilege unless

all friends who are as good as relatives to me are also allowed to be present.

3. If this is also not acceptable to government, then those who have been allowed to visit her will be sent away by me, and only those who are in the camp (detenus) will attend the funeral.’

I added I have always wanted whatever the government did to be done with good grace, which, I am afraid, has been hitherto lacking. It is not too much to expect that now that the patient is no more, whatever the government decide about the funeral will be done with good grace.

We cremated her the next day beside the spot where Mahadev had been cremated. Devadas performed the last rites.

Messages of condolences came the next day from the viceroy, the governor of Bombay and several others. It was noticed that none came from Lord Linlithgow and from Quaid-e-Azam, M. A. Jinnah.

On 24 February, the family and associates went to collect the ashes. Her green glass bangles were found there—unburnt, untarnished. That evening I had a meal with the three sons present—Harilal, Ramdas, and Devadas.

In reply to a question in the legislative assembly, Reginal Maxwell, the Honorable home member, was reported to have said in answer to a question from K. C. Neogy: ‘The provision for the expenses of Mr Gandhi and those detained with him in the Aga Khan Palace amounted to about 550 rupees a month.’ I wrote to the Home Department on 4 March to say, ‘Virtually the whole of this expense is, from my point of view, wholly unnecessary; and when people are dying of starvation, it is almost a crime against Indian humanity. I ask that my companions and I be removed to any regular prison government may choose.’

(Excerpted with permission from Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s ‘I Am an Ordinary Man’; published by Aleph Book Company)