The language of theatrical space

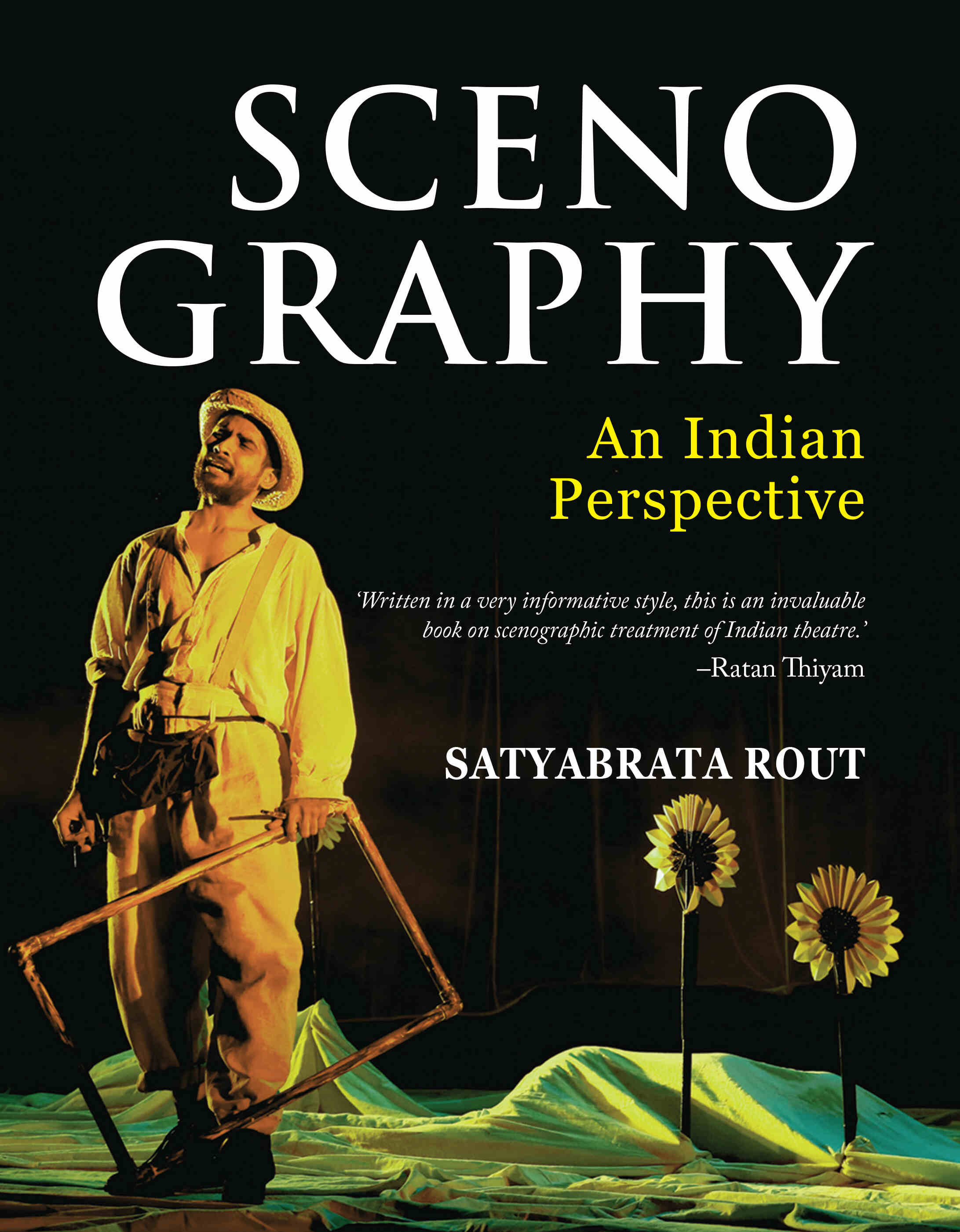

Satyabrata Rout’s treatise, Scenography, lays down the foundational intricacies of the art of ‘writing the stage space’ — filling the huge gap prevailing in the Indian theatrical landscape; Excerpts:

Theatre has undergone radical changes since its genesis. With the passage of time, its form has continually been modified, and at times, even restructured. It has witnessed its fair share of highs and lows. While historically theatre has been used as a medium to promote communal harmony and propagate social awareness, it also provides a platform for the refinement of culture and the society at large. The past serves as a repository of the events that contributed to the reformation of theatre spaces and performances in the course of its long existence. With changing times, theatre has faced almost the same problems in both the East and the West. In the process of adapting to the changes in civil society, it had to accept modifications to its form and flavour, and thus it remains relevant even today in spite of remaining dormant for years.

The brilliance of theatre is in bringing together and uniting people, which has kept it in good stead for years together. Since this art form evolves through human gestures and social expressions, it has come to be the most potent channel for communicating to the masses. It articulates the current time and space, for theatre lives in the 'present'. Where all other art forms are displayed after completion, theatre is created simultaneously with its performance; it is immediate. For instance, a painter may display his work only after applying the final stroke to his creation, a writer publishes his manuscript when he is done with writing, but a performer showcases his art while he is engaged in its making. Thus, the time of creation is concurrent to the time of presentation in the context of performing arts, making it the ideal medium for the exchange of human experiences.

Theatre is essentially an activity involving two groups of people—the performers and the audience. These two groups, or even two individuals, come together in a common space, be it formal or informal, and theatre begins on the spot. A story unfolds in front of the spectators, with both groups sharing their experiences during the process of unfolding. The act is at once simple and instantaneous, and therein lies the beauty of theatre. From commonplace community activities to the most intricate performances of the world, from street presentations to sophisticated productions, each subscribes to a common phenomenon—the sharing of human experiences. Elaborate spaces and technological fripperies are inconsequential to this exchange. Even a well-plotted story with provocative dialogues proves trivial. Theatre can thrive without these aspects, but not without the presence of the spectators.

Jerzy Grotowski, a noted theatre practitioner of the 20th century, rightly argues: 'By gradually eliminating whatever proved superfluous, we found that theatre can exist without make-up, without autonomic costume and scenography, without a separate performance area (stage), without lighting and sound effects, etc. It cannot exist without the actor–spectator relationships of perceptual, direct, "live" communion.' Analysing this revolutionary contention of Grotowski, we realise the importance of three essential elements in the making of theatre—actor, spectator and performance space (formal or informal). With these three fundamental ingredients, theatre has been able to serve societies across civilisations and times. This is and always has been the aim of theatre, and it will continue as a contemporary and relevant art form as long as it remains true to its purpose.

The Performance Space

A performance space is a distinctive space, physically and perceptually different from our understanding of the concept. Within this space, many direct and indirect transformations are affected. As Prof. Gay McAuley points out:

What is presented in performance is always both real and not real, and there is constantly, interplay between the two potentialities, neither of which is ever completely realized. The tension between the two is always present, and, indeed, it can be argued that it is precisely the dual presence of the real and not real, that is a constitutive of theatre.

A story, a character, a concept, or even a physical being, during a presentation is allowed to pass through multiple spatial and temporal transformations without compromising its distinctive presence. Interactions between the performers and the audience are facilitated by the space itself. Such a space is both flexible and adaptive, allowing for a constant interplay between 'seeming' and 'being': the conflict between the fictive reality of character, plot and ambience, and the physical reality of the performers, the stage and objects. Art historian Joseph Roach also emphasises this concept, opining that a 'Theatrical performance is the simultaneous experience of mutually exclusive possibilities: truth and illusion, presence and absence, face and mask.' This coexistence of contraries is only possible in a performance space. Enthusiasts, or those who have witnessed and experienced a theatrical presentation, must have perceived something unique and mesmerising happening in front of them, confined to the theatre space but distinct from any banal daily activity. The spectators and performers are well aware of the physical space they share during a performance. But within this physical time and space, both also experience a dramatic space—a fictional world of imagination. Facilitated by the performer(s), spectator(s) are able to visualise a different person in a separate time and space. This, in essence, is a simultaneous overlay of two different realities, possible only in a performance space. Ronald A. Willis of the University of Kansas observes:

Spectators must thus deal with a dual-leveled encounter which trumpets the fact that in the theatre two modes of experience, two kinds of event, can and do exist in the same space at the same time. This fact, although seemingly counterintuitive, nurtures the essence of theatrical magic. Much that we regard as performance magic springs from a complex experience of immediate presence. Audiences and performers are in each other's presence as both real and imagined beings.

Defined Space

When appreciating a sculpture or any architectural monument, one may evaluate its form and structure from various angles by moving around the structure. But this may not hold true for a live performance; the visual range of a spectator is less than 180°. An audience may not move with the performers to appreciate the play since one's position in a theatre is almost fixed, though there are certain exceptions. At any given moment, one can see only a portion of the performance space and the activities in that space—the entirety of the visual composition evades a seated spectator. This configuration of 'seeing' dictates the visual compositions in a play. The art of theatre, in this respect, differs from that of a film, television and similar art form.

In general, a theatrical performance cannot shift the action into real space. All activities take place in a delineated space that is restricted and defined, limiting the performance area. Sometimes only one of its sides is open to the audience; in other kinds, the audience may encircle the performance space. Occasionally, in environmental theatres or site-specific performances, where the spectators move with the scenes, the action takes place in separate, preordained locales; spectators and performers share a common space. But, irrespective of the style of performance, this space is always defined, and the world of imagination has to be realised within its framework. This is the limitation of theatre, but in this limitation also lies its inherent strength. Such is the irony of this art form—since everything has to be visualised within a particular space, regardless of size and shape, theatrical performances become symbolic, imaginative and creative. Each performance creates its own grammar and vocabulary, and is expressed through the medium of metaphor. It resembles life, but not real life per se. Life is subject to interpretation in this art form.

Metaphor, the thrust of creation—or how 'life' is reimagined in a defined space—becomes essential in a theatre presentation in addition to its functionality. The purpose of this metaphorical space is best served when it is meaningfully played out by actors during a performance, which is further enlivened by dramatic developments. As the show progresses, the limited space breaks its barriers and penetrates into the psyche of the audience, allowing one to visualise unseen ideas and experience new events along with the dramatic action: a gamut of emotions thus flows through the audience gallery.

Magical Space

A theatregoer may have experienced the magical transformation of space during a performance. When the third bell rings and the auditorium lights are dimmed, the world around us becomes obscure. With the rising curtain and growing intensity of onstage lights, another world begins to take shape in front of us. Gradually, we are drawn into this strange and unreal world, and begin to experience its quirks and idiosyncrasies. It permeates our imagination, such that we lose ourselves and breathe in tune with the dramatic events unfolding before us. These events then assume the form of real life: performers transform into characters; a plain wooden platform turns into a magnificent palace, an ordinary chair assumes a royal throne, a painted cut-out of a tree expands its foliage to become a dense forest.

To better understand the idea of magical space, let us discuss a few examples of such performances. In 2011, I directed Matte Eklavya. The acting area was segregated into two distinct parts—an outer and an inner space; it was the demand of the performance design. Generic actions were presented at the downstage while a psychological space—the inner space, demarcated by a black net curtain—was created at the upstage. The black net seemingly merged with the background, making the entire space appear as a single unit. On occasions, the audience could perceive an inner space magically developing in the empty performance area, exploring simultaneously a separate time and space. In this inner, psychological space, one could see Eklavya, a young tribal archer from the Mahabharata, practising archery in a dense forest—the forest, of course, existing only in the imagination of the audience. In another sequence, Maharishi Vyasa and Lord Ganesha are seen engaged in writing the great epic when Eklavya suddenly appears in the dreams of Ganesha, realised through the psychological space upstage. In a subsequent scene, Vyasa asks Ganesha to reveal Eklavya's mental state after he has been rejected by Guru Drona as his disciple. To realise the drama and emotions, Ganesha invites Vyasa to walk into his dream and watch the event in person. With that, the scene

materialises upstage, behind the net curtain, where Eklavya appeared practising archery in front of an effigy of Guru Drona. Both spaces, the outer and the inner, are juxtaposed in the performance area, where each space actually represents a different time and space, far removed from one another.

(Excerpted with permission from Satyabrata Rout's Scenography; published by Niyogi Books)