The art of writing lives

The literary class of ‘biography, memoir and autobiography’ cannot be stereotyped as a Western concept, for it has been chronicling prominent Indian lives for ages, and should continue to document the circumstances and diversities in the lives of ordinary citizens

Reading about someone is not exactly helpful to me”, a young lady doctor told me so when we were discussing the book ‘Lady doctors’ by Kavitha Rao, which empathetically chronicles the untold life stories of the first six women doctors of India, from the 1860s to 1930s. A few days later, she tried to patch up on the topic, “horror stories and detective novels give me new ideas”. She left me unsure, whether such pursuits will help in her clinical skills!

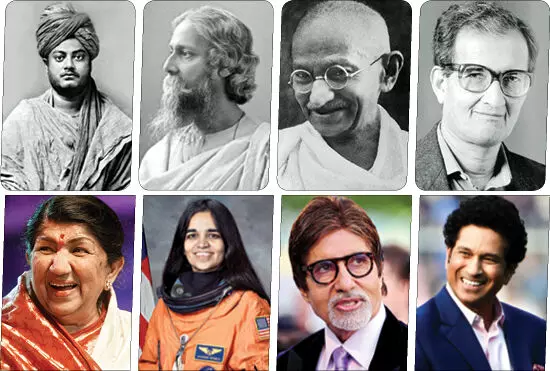

Life-writing, which falls into the literary class of ‘biography, memoir and autobiography’, is usually clubbed as non-fiction literature. Poetry, drama, and novel form the other class called ‘fiction’. Encyclopedia Britannica calls biography and autobiography as historical materials rather than literary works. It is no wonder that we are still debating about the genre and positioning of ‘biography, memoir, and autobiography’. Then there is the other debate, beyond its classification within the literary world. There is a perception that biography and autobiography are Western practices. As if when you enter a book shop or search online, your mind would be tuned to look for a book on Aphrodite, the Greek Goddess of love and fertility; or, Hollywood’s Robert Redford of ‘The Horse Whisperer’ fame. Yet, there is every reason to look eastward. From the 7th-century Harshacharita by Banabhatta, which presented a partial biography of King Harshvardhan, to right up to Mahatma Gandhi’s The Story of My Experiments with Truth (1927-1929 in Gujarati, then the first English edition in 1940 by Mahadev Desai), life-writing has remained a part of India’s social records. Amara Jibana — the life of a woman in the 19th-century rural India — by Rassundari Devi was published in Bengali in 1876 and read in homes. “Even now I remember those days. The caged bird, the fish caught in the net” — these written words from Rassundari, as a rebellion against the social order of her time, still count after nearly one and half centuries, when sorrow and rage pierce the women in the USA about their abortion rights. Here, the life-writing from the east can show a mirror to the West.

Much too often, a biography is meant to document the real life of a hero or a villain, in order to satisfy the ‘great man theory’. It is usual to perceive that a biography should choose one of the two patterns: a) a factual and chronological arrangement of the external events in the subject’s life; and (b) shaping the historical contexts through the life of an individual. Every reader of a biography or autobiography in the pre-internet era would be swayed by such larger-than-life individuals. As a medical student in the 1970s, the life and philanthropy of John D Rockefeller (1839-1937) towards medical education and research would enthrall me. Those were unalloyed reverence, until the stories around the monopolistic expansion and business practices of Rockefeller father-son duo tumbled out through the web and social media during the last decade.

Coming back to the young lady doctor, instead of reading ‘Strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’, the life and toil of Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy, the girl born to a Devadasi, would reveal the power of education, emancipation, and health-for-needy. Muthulakshmi’s entry into the Madras Medical College in 1907 as the only girl student is a milestone, and not a myth. From the mid-20th century, the writers of biography, and equally of autobiography, have engaged in the skill and craft to show the individual in flesh and blood with ‘warts and all’. It is no more a matter of importance to put together the dates, events, places, and persons around the protagonist as a superhuman being who shaped the world. The obsession with competitiveness seen through the Satyam scandal (2010) as the lessons for corporate fraud has a narrative as much as the clothing fetish of Steve Jobs for turtleneck t-shirt.

When India is moving earnestly to become a significant global player, the lives of ordinary citizens who break the barriers, like that of Kalpana Chawla, become uplifting. While framing the Constitution of India, Babasaheb Ambedkar would state about the basic framework of governance, “Equality may be a fiction, but nonetheless, one must accept it as a governing principle”. Hence, much as we learn that equality, and furthermore diversity, are facts of life, yet those no more continue to remain illusory. The literary genre of “biography, memoir and autobiography” has the embryonic agency to find writers who would chronicle the circumstances and diversities in the lives of India’s citizens. Human beings are uniquely endowed to dream and labour.

The writer is an oncologist and was a Professor at AIIMS, Delhi. His book “Father-a policeman & Son-an oncologist” has been recently published by Har-Anand Publications, Delhi.

Views expressed are personal