Standing tall against the monarch

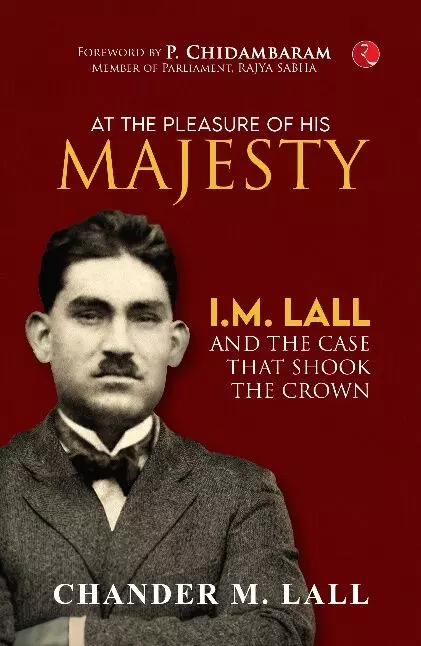

At the Pleasure of His Majesty by Chander M Lall offers an in-depth exploration of the 1948 Privy Council ruling and the preceding events, encompassing the experiences of his Hindu family in Lahore during the Partition. Excerpts:

In its decision dated 18 March 1948, titled ‘High Commissioner for India and High Commissioner for Pakistan v. I.M. Lall’ authored by Lord Thankerton, the Privy Council agreed with the findings of the Federal Court that the person being dismissed or reduced must know that the punishment has been proposed for certain acts or omissions on his part and must be told the grounds on which it has been proposed to take such action and must be given a reasonable opportunity of giving show cause, stating why such punishment should not be imposed. These processes were not followed in the present case. Accordingly, the Privy Council eventually found that ‘the order of August 10, 1940, purporting to dismiss the respondent from the Indian Civil Service was void and inoperative, and that the respondent remained a member of the Indian Civil Service at the date of the institution of the present action on July 20, 1942’.

The other question, however, was whether damages and arrears of pay could be awarded in the case. On this, the Privy Council reversed the decision of the Federal Court holding that public servants are prevented from suing the Crown for their pay. This, the court held, is on the assumption that a public servant’s only claim is on the bounty of the Crown and not a contractual debt. The court held that there is an implied condition in every contract between the Crown and a public servant. The condition stipulates that the public servant has no right to their remuneration which can be enforced in a civil court of justice. The only available remedy under their contract lies in an appeal of an official or political kind. The Privy Council did, however, grant costs but did not accede to the costs of his coming to England from India.

According to the Privy Council, the employment of public servants was ‘to continue during the pleasure of His Majesty, His Heirs and Successors’. The employment contract is given under the hand of the Secretary of State for India.

Inder Mohan had been dismissed by an order made under the hand of the Secretary of State for India, and as he was liable to be dismissed at the pleasure of the Crown, he could base no complaint against his dismissal on the contract of service and did not, in fact, do so. He founded his suit on the claim that his dismissal by the Crown from the ICS, of which he was a member, was void and of no effect, as certain mandatory provisions of the Government of India Act, 1935, had not been complied with. The Judicial Committee accepted this claim and thereupon made the declaration that the purported dismissal of the respondent was void and inoperative and he remained a member of the ICS on the date of the institution of his suit.

Impact

This is an important decision for service law jurisprudence in India and has been cited with approval in over 10 Supreme Court decisions subsequently. The decision was a turning point for many reasons. The first being that a subject of the British Empire had won against the Crown. This was the only case with such a result. Never in the history of the Empire had the subject ever prevailed over the Crown. By dismissing him from service, the Crown had violated the basic tenets of service law of not giving him an opportunity to defend himself against the charges levied against him. The decision significantly watered down the existing belief that all civil servants enjoyed their position at the pleasure of the Crown.

The decision formed the very basis of the principles of service law of informing the person of the charges framed against them and giving them an opportunity to show cause and defend themself against the charges. This paved the way for Article 311 of the Constitution of India, a provision dealing with the dismissal, removal or reduction in rank of persons employed in civil capacities under the Union or a state. Article 311 essentially puts restrictions on the pleasure doctrine as discussed in Inder Mohan’s case.

In another case titled ‘State of Punjab v I.M. Lall’ in which Inder Mohan was represented by D.D. Chawla, C.L. Choudhary and Amar, a Division Bench of the Delhi High Court consisting of V.S. Deshpande and B.C. Mishra narrated the three decisions of the High Court, Federal Court and the Privy Council, and held:

In penultimate paragraph, the Judicial Committee held that ‘removal of I.M. Lall from service was void and a declaration was granted that on the date of the suit that is to say in June, 1942, he remained in service’. This decision was incorporated in an order in Council. In the eye of law, therefore, Mr. Lall never had any break in service and his removal from service having been set aside and declared void and declaration having been granted that he continued to remain in service, the legal effect was to treat Mr. Lall as in service during the whole period from 1940 to the date of his suit and from the date of the suit till the decision of the Privy Council and, thereafter until legally terminated. During this period, he would naturally be entitled to receive his salary and allowances as if there was no break in service

Justice had been served. The pleasure of the Crown could not be a curtain behind which the servants of the Crown could undertake capricious or arbitrary actions. The pleasure shall be regulated by rule, said the Privy Council. Inder Mohan was reinstated. His date of re-appointment was 27 November 1948, with a salary of `2,250 per month with an additional, `400 and overseas pay of £30 per month.

(Excerpted with permission from Chander M Lall’s At The Pleasure of His Majesty; published by Rupa Publications)