Opulent exploration of timeless artistry

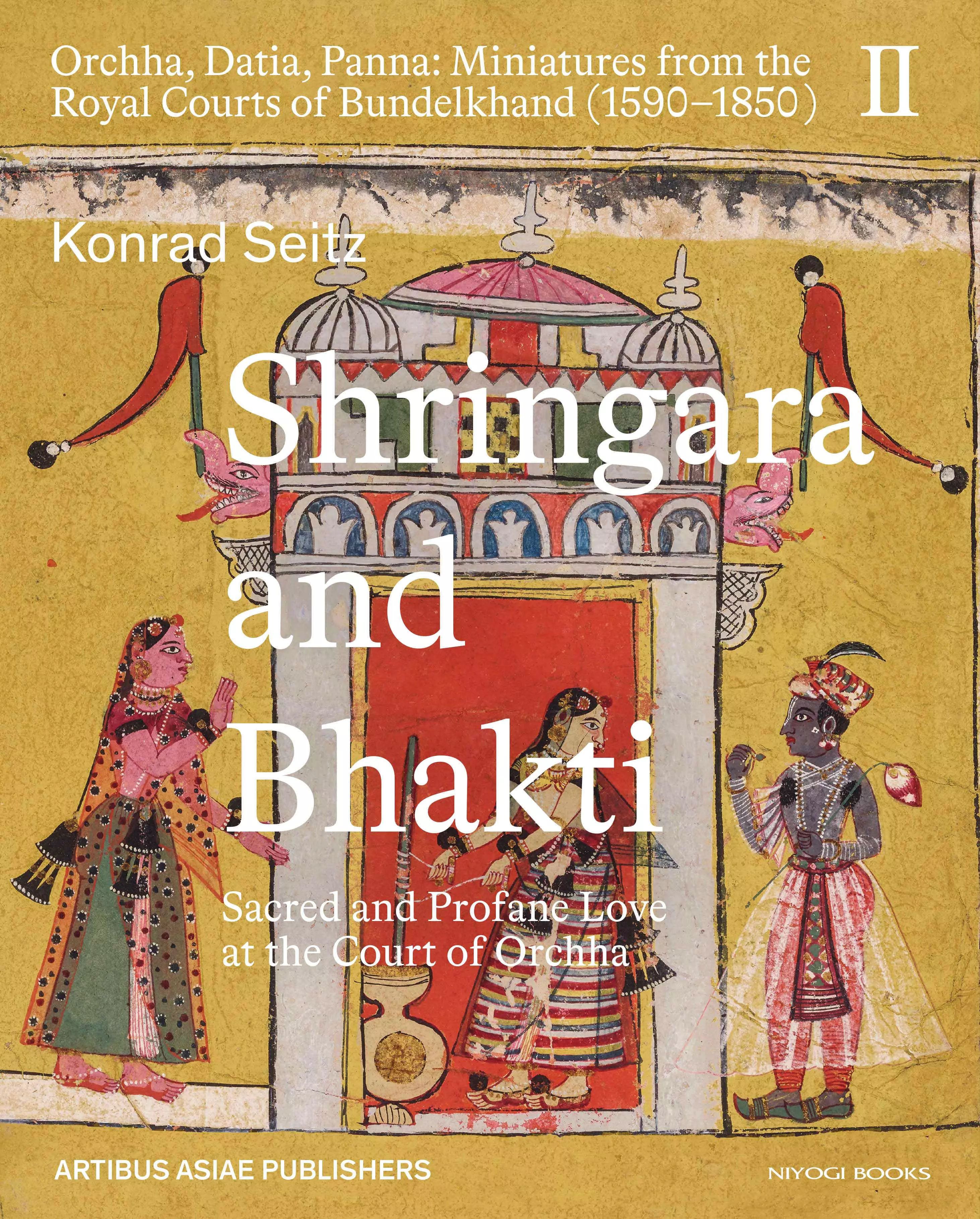

This second volume in the series Orchha, Datia, Panna: Miniatures from the Royal Courts of Bundelkhand (1590- 1850) by Konrad Seitz is a richly illustrated treatise which analyses and interprets author’s 100 plus paintings that represent the prime of Orchha school in the 17th century. Excerpts:

Jhujhar Singh’s rebellion against Shah Jahan ended in 1635 with the latter’s conquest of Orchha and the sacking of the city and palaces. Jhujhar Singh himself was cruelly killed by Gond tribal people as he fled to the Deccan. Years of chaos and guerilla warfare followed, until finally Shah Jahan installed Pahar Singh, a brother of Bir Singh, as raja in 1641 and peace was reestablished. Orchha, once the richest of the Rajput states under Bir Singh and encompassing most of Bundelkhand, became a minor principality between the Betwa and Dasan Rivers.

When the artists resumed work, painting split into two distinct styles: Style A was based on the Jhujhar Singh style, style B on the Mughalizing Bir Singh style. Furthermore, there was a difference in the illustrated subject matter.

The miniature series in style A illustrated the Krishna- and Rama-bhakti works of the Bhagavata Purana and Ramayana as well as the Radha-Krishna lyrics of Keshavdas’s Rasikapriya. In addition, they interpreted and visualized the various musical moods of the Ragamalas as Radha’s devotional love feelings in her different states of separation from and union with Krishna.

The series in the Mughal-influenced style B, on the other hand, illustrated secular erotic Sanskrit poetry ( kavya ) such as the Amarushataka, or “One Hundred Stanzas of Amaru,” an understanding of which presupposes literary connoisseurship, and they represented the ragas and raginis of the Ragamala series as ladies and gentlemen of the court.

The reference series for style A is the so-called “Boston” Ragamala from c. 1640–45, that for style B the Amarushataka series dated 1652. Let us examine the difference in the two styles by comparing the depiction of Madhumadhavi Ragini in style A and style B.

The picture in the native style A ( fig. 19 ) comes from the famous Boston Ragamala – those twenty-three paintings which Coomaraswamy bought in the bazaars of Old Delhi around 1910 and which defined for him the essence of native Indian art. The second picture ( cat. 41 ) comes from a series in which the Mughalizing style of the Amarushataka from 1652 reached a climax.

The rasa of the Madhumadhavi melody is visualized by the emotions of an abhisarika nayika hurrying to her paramour through the frightening darkness of a stormy night. She arrives at her lover’s pavilion just as a flash of lightning within the rain clouds – a metaphor for the sexual act – startles her and makes her stop. To protect herself, she throws up her arm; simultaneous desire for and fear of love are colliding in Madhumadhavi’s heart.

Both pictures use the same iconography, yet they could not be more different in the mood ( rasa ) they convey to the viewer. The Madhumadhavi image in the Boston Ragamala is sheer passion, sacrificing to expressiveness any realism in the rendering of figures and pavilion. The ragini, silhouetted in burning red against the deep black of the night, stands in front of her lover’s palace. She looms high above him yet stares back into the surrounding darkness as a peacock calls out abruptly and soars into the stormy clouds. Within the palace, her lover, he too with a staring look, reclines tensely on an enormous bed, which is thrown crosswise in front of the room as if partaking in the wild desire of the lover.

So much for the Boston Madhumadhavi. Let us now look at a Mughalized Madhumadhavi painted at Datia around 1670–75. There, we find the exact same iconography, yet the sublime expressiveness of the Boston image has been sacrificed to beauty and ornament:

( 1 ) The boldness of the Boston picture’s empty backgrounds is here weakened by the pearly raindrops and the heavy ornamentation of the pavilion. The color composition as a whole is dominated by the radiance of the gold and the brilliance of the white figures and palace facade.

( 2 ) The figures are finely drawn with flowing lines and slightly modeled. Their clothes are adorned with elegant patterns: Madhumadhavi wears a transparent muslin sari through which the red stripes of her skirt shine through, while her lover wears a transparent jama through which the green stripes of his trousers shine through. Everything is drawn in minute detail and with the utmost precision. For example, one may note on the ragini’s raised hand the tiny red dots representing a henna pattern.

( 3 ) To appreciate the full glory of the picture’s ornamental beauty, however, we have to look up at the palace’s rooftop structures. The projecting eaves are decorated with a leaf-and-flower arabesque rendered in exquisite pale pastel shades. This is followed by a second frieze that repeats the first arabesque but in the principal colors red, green, and blue. And, finally, completing the ornamentation are the parapet of the roof terrace, embellished with a flower medallion pattern, and the decorative eaves and striped domes of the chattris.

Let us now draw the conclusion from this comparison: Clearly, the aesthetic goals of the two paintings are fundamentally different. The goal of the style A image is the native Indian goal of evoking the sublime power of great, even savage emotions, while the goal of the style B image is the Mughal goal of expressing a form of beauty that combines the European idealizing mimesis of nature and radiant Persian ornamentality. This contrast makes it evident that miniatures in the native style A and those in the Mughal-influenced style B were produced for different patrons and by different painter families. In what follows, we shall assume that the miniatures in style A were painted in workshops in Orchha, and attribute those in style B to Datia, which after 1635 became an independent state and developed into an important cultural center.

The Boston Ragamala Style

When after the catastrophe of 1635 painting was resumed in Orchha, the painters continued working in the Jhujhar Singh style though in a simplified version and a smaller format. It was art in poorer times. The basic series that ushers in the new Period III A1 is the Boston Ragamala. We shall study the transformation by comparing the Khambhavati of the Boston series ( fig. 12 ) with the one in the Jhujhar Singh series ( cat. 8.1 ).

In the Boston Khambhavati, any detail of the Jhujhar Singh composition not necessary for the iconography has been stripped away: the accompanying attendant, the two flowering banana trees, the lotus pool with the stairs leading down to it, and the lower story of the palace with its three arched openings. The representation is strictly concentrated on what is essential.

However, what is lost in decorative beauty is gained in emotional expressiveness. Freed from distracting details, the bold color fields can now exert their full power. The color scheme of the Boston Khambhavati is dominated by the large black field of the sky. Black has become the primary color! It is no longer only a color for the sky area, but can also be used as the main field. Here, as so often in the series, it combines with the deep-blue background against which the two figures are set, thus creating a dark, mystical-erotic atmosphere. Green, on the other hand, and especially the calming green-red complementarity, is completely eliminated from the series. The Boston Ragamala style is one of “savage vitality,” as Coomaraswamy characterized it, created by painters who were “occupied entirely with expression.”

(Excerpted with permission from Konrad Seitz’s Shringara and Bhakti; published by Niyogi Books)