Maps and Milestones in India’s history

Sanjeev Chopra’s We, the People of the States of Bharat is a meticulously researched and well-contextualised account of reorganisation of ‘all states’ in post-independence India

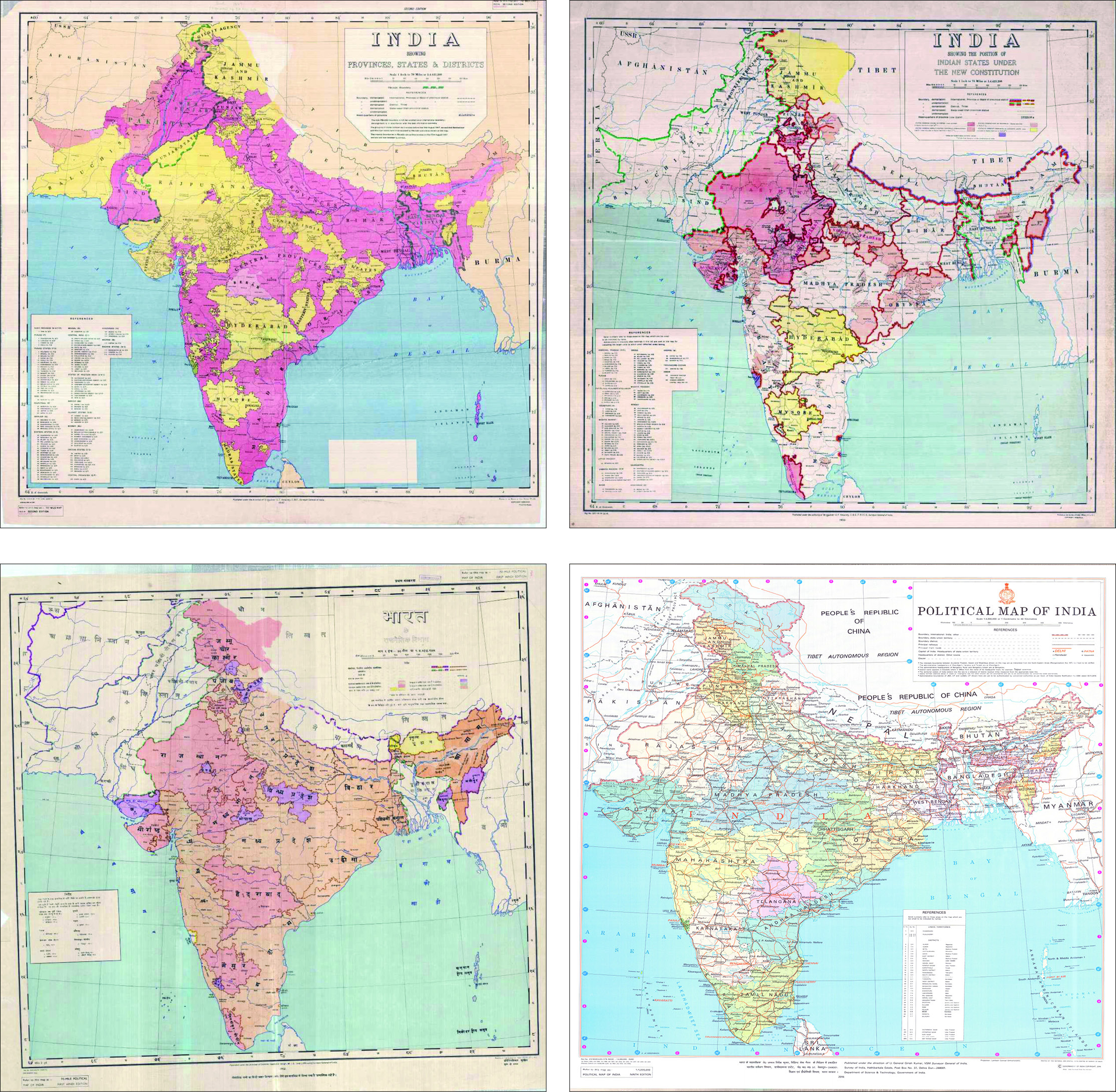

Any student of history would be fascinated by the question of when India actually became a nation state. Its history, from earliest times, through empires and princely kingdoms, big and small, has been of shifting boundaries. It was only when we got independence in 1947 that, in a sense, we got the geographical shape of today, threatened by the irresponsible claims of China and Pakistan. Furthermore, we also emerged as a nation in the period 1946-50 with the herculean efforts of Sardar Patel and others as they incorporated the princely states in the Union, and later, the small foreign territories were added. And yet, no other country has been witness to such a large-scale re-adjustment of internal boundaries thereafter. That in itself is a good reason for us to read the book titled ‘We, the People of the States of Bharat’. It is a riveting story that has been told in great detail by writer, thinker and ex IAS officer, Sanjeev Chopra.

The political history and processes of post-independence India have been well studied. However, the subject is so vast that it offers many different areas and perspectives for study. It is to the credit of Sanjeev that he has found a gap and has chronicled one important aspect of it which has been dealt with in bits and parts in the past in articles or reportings or even parts of books etc. He provides a holistic view and has put all happenings at one place, perhaps for the first time. The reader at least has the opportunity to get all the related information at one place. And he has done so after a lot of research. His studies provide more than just a glimpse of what has gone into the making and remaking of states. There is plenty for any reader to dig into whichever direction he/she may look at from madhya bharat, reaching out to all the extremities. The extensive notes and bibliography show how hard the effort has been in putting things together and are an inducement to further reading.

The changes or re-adjustments to the states/UTs have been caused due to a mix of political issues, regional aspirations, language divide, territorial legacies, religious matters, and, of course, external jurisdictions. This is another aspect of the phenomenal diversity within this ancient land, bound together by a rich civilizational history and some concept of Indianness. The book covers all states, as each has been affected by some change. I was indeed struck with the newfound realisation that every state and UT (including Ladakh and Andaman & Nicobar Islands) has seen a change in nomenclature or status or territorial adjustment since 1947, yet the country, as a geographical entity, has strengthened. All of us should be aware of these historical developments because they are important for our understanding of the unity of India. As Sanjeev says, India has, during these years, and with these developments, re-imagined itself, showing innovative ways of accommodating political, cultural and linguistic aspirations and differences. It is also a story then of statesmanship over a period of time where a broader vision of nationhood has prevailed.

The book covers all states. The story of each state is interesting in itself because it has its own background and interplay of different forces and aspirations. Many of us have seen most of these events happening, but they are all worth looking back again for a better understanding, with both hindsight and the perspective of so much time having passed, and considering the essentially holistic nature of the outcomes. But each is different in its own way, and actually quite different which makes for a variety. Take the case of Sikkim, an important event which happened when I had just joined the IAS but one of which there is only a dim recollection of. Interestingly, there are four perspectives of the events briefly discussed in the book written by journalists, civil servants and foreigners. What it shows is the interplay of various factors. Each is different. For the history student, reading them side by side, would show that, as Sanjeev says, history is but an interpretation and perspective of facts, and that no one, especially the contemporary observer, can claim to be ‘objective’. This approach will add spice when you read the many stories in this book.

I am, however, left with a sense of foreboding. The issue of political power has become increasingly dominant and there are new divisions developing within the country. Sanjeev notes that the formation of Telangana has rekindled hopes in Maharashtra and Bengal for a second state. There has been talk since long of UP and Bihar being too big. At the same time, these states, particularly UP, have become the source of political power in the Union. If the growing demographic differentials lead to increased electoral constituencies, making for even a still higher Lok Sabha seats number for these two states, there may be adverse reactions elsewhere, especially as there is some resentment at resources flowing from south and west to north and east. What next, the question which Sanjeev asks, is therefore very important for the balanced growth of the country. His book provides all of us an opportunity, and a better understanding, to reflect upon these issues. That is a good enough reason, too, for us to read his book.

Views expressed are personal