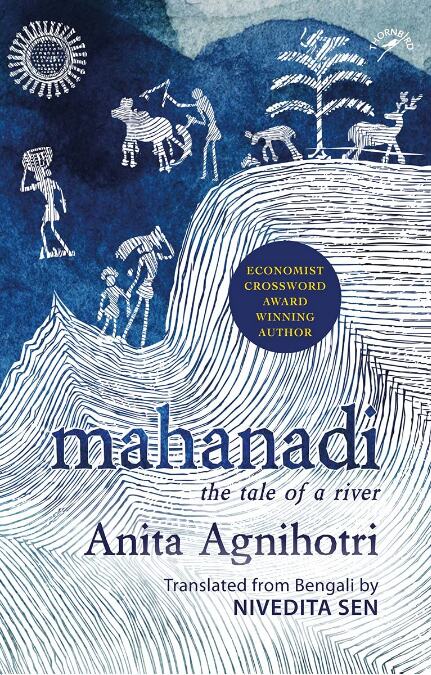

Life along 'Mahanadi'

Anita Agnihotri’s Mahanadi — skilfully translated by Nivedita Sen — tells the tale of the epic river, intertwined with both happy and sorrow realities of the lives of the books’ vibrant characters; Excerpts:

One can hardly imagine now what a long journey it was fifty-seven years ago. At one extreme end of it was Kutherpali village on the western bank of the Mahanadi. And how far away near its southern tip was Jujumura! A minibus now comes to Sambalpur town from the turn to Hirakud. From there, one can take the trekker or another minibus. If you have to go to Nuabalanda, there is no way of course except to take a hired car or trekker from the block district of Jujumura. There was no road at all about four years ago. One had to go on foot for the last three-four kilometres. Unpaved and broken, that flooded road was such in the monsoons that the owners of cars would desist from having their cars traverse that path. Two years ago, two Maoists and two policemen were killed in an encounter. Papers and documents were seized, along with two disguises of police uniform, bullets and gunpowder. A police constable in actual uniform from the Sambalpur Armed Police, Siddhinath, had been struck by a bullet that had pierced his chest and found its way out through his back. After that, the government took the decision to construct a concrete road. That road has of course been built – it is nice though a little crooked. It is a tarred and macadamized road, although it has started getting eroded already with the constant inflow of water due to not having built a water drainage system next to it.

One can guess that the appearance of the road will not change, either until the road erodes to merge with the earth, and innumerable wild weeds grow around its skeletal frame, or until another encounter takes place. The people in this village had come from Kutherpali village that was on the bank touching the Mahanadi on the west. There were no villages here then – only rocky plateaus and endless forests. They had come in a team walking all the way from the edge of the Mahanadi, crossing the town of Sambalpur on the way. It had taken them two-three days. They had stopped on the way, and cooked and eaten their meals under the shade of trees. With them were all the goats and cattle that were fit to walk. The lorries loaned to them by contractors had arranged to transport only the doors and window frames of their old houses and the paddy they had stored in their homes. The ripe paddy in their fields had got drowned as they had watched helplessly. The flood that had come would sink over 140 villages that were strewn on either bank of the Mahanadi.

The government had directed them to leave behind all the stuff, as well as the unreaped crops and plants, saying, 'You will be given money that will be equivalent in terms of the price of all those things you have left behind.' That compensation had never come their way afterwards. They had had to come away after getting Rs 400 per acre. This was the last refugee group of the people displaced by the Hirakud dam who had had to go away from Kutherpali. Until the water level reached up to their nose, they had sat there believing that they might eventually not have to get evacuated from their village – perhaps the work of building the dam would get stalled, or maybe the government would change its decision, and such like.

The women were crying in spasms as they went along. They had wept all the way, and in different ways. They had blended the lamentation in their hearts with a sort of broken melody and poured it all into the singing of old songs. The faces of the men were stern, grim and despondent.

The government had driven them away. This had really hurt all of them. This was the government of independent India.

What a contrast there was between the perennially overflowing Kutherpali, and Nuabalanda of the Jujumura panchayat, surrounded by hills and forests! One had to go a long way to the south from Sambalpur and then turn inside again. From their habitation at Kutherpali, one could see the rolling hills of the Dungri mountain range. That sight was very charming, like a picturesque landscape in subtle green. Here, a mountain virtually stumbled over at their backs and a wild forest caused terror in their minds, filling their eyes with tears in fear and anxiety. The village of Nuabalanda is enveloped by forests. Even after five decades, if the forest has such prowess, you can make out how it was at that time. Now, however, there are roads and junctions, wells at which people draw water, school buildings and playing grounds. Fifty-seven years ago, the entire area was a dense forest. They had dug up a little piece of it and fashioned it into a village. On the way were Ghenupali and Barashahi – two large villages. After that, there were two huge, steep hills – Bander and Karrapat. There was a way between the two hills.

(Excerpted with permission from Anita Agnihotri's Mahanadi; published by: Niyogi Books)