Letters, Lineage and Liberation

In Lavanyadevi, Kusum Khemani’s intergenerational narrative reveals how women shape, question, and inherit values across shifting social and spiritual landscapes

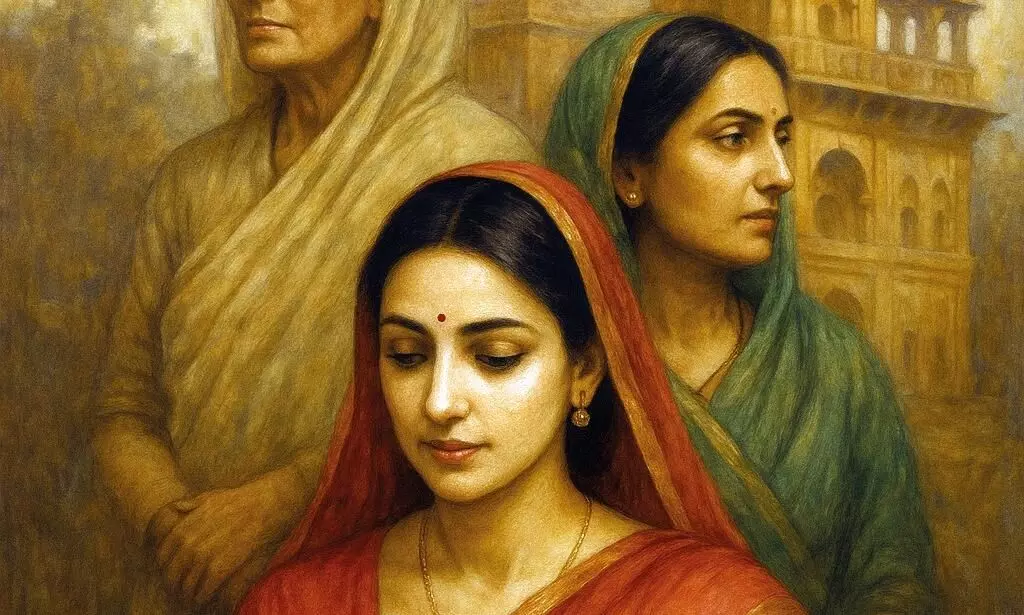

Certain answers to the eternal quest of self-understanding emerge in Kusum Khemani’s 2013 novel Lavanyadevi, translated from the Hindi original to English by Banibrata Mahanta in 2024. A sweeping intergenerational story set within an aristocratic zamindar family, this book offers a keen lens with which to examine how we are shaped by our ancestors, who in turn evolve through different economic and social contexts. Migration has been a defining aspect of Marwari identity, and a backdrop of their shifting landscapes over two centuries highlights tensions of Yugadharma between Indic tradition and Western modernity for three clear-eyed matriarchs.

The daughter of an impoverished widow, beautiful Prabhavatidevi builds a charmed life in Dhaka as the second wife of an enamoured nobleman. Her daughter Jyotirmoydevi consolidates the family legacy in Kolkata through diligent endeavour. And her daughter Lavanyadevi grows up to be a veritable paragon - but without cloying sanctimony - who returns often to the lessons imparted by the women before her. The fairy folk-tale realm of the story casts these three within the light of mythical women like Ahilya, Shakuntala, and Draupadi, as well as archetypal goddesses like Lakshmi, Saraswati, and Durga. Their fine qualities are spoken of admiringly by many in mythologised memory; inner worlds are revealed through journalistic record. Lavanyadevi realises the depths of her restrained mother’s admiration for her upon discovering an exultant entry in Jyotirmoydevi’s private diary: “To decline an offer made by a director as reputed and acclaimed as Mr. Sen was something that even celestial nymphs like Urvashi and Menaka would have found difficult. But here was my Lavanya, an ordinary human being… even at her young age, she was able to understand the transience of external appearance.”

It is this earnest human effort to inculcate values of inner refinement which steer the text away from idealised “Mary Sue” characterisation or the faultless piety of women in K-serials. Even its most venerated characters - like Lavanyadevi, who is graceful in both maternal and professional identity - have to confront their egoistic frailty and falter in the face of failure.

After realising that her moral objectivity is subject to complex subjective considerations, a widowed Lavanyadevi decides to forsake her Kolkata mansion for spiritual simplicity in the Uttarakhandi mountains: “If I do not search for these answers today, the python of doubt will grip me in its deathly embrace and swallow me alive.”

Despite her Buddha-like detachment, enduring ties to affectionate family members root Lavanyadevi to worldly issues. She struggles with the inherent sensation of displeasure that she feels upon hearing about “explicit sexuality”, but recognises too that this bias is unbecoming of her intuitive impulse towards unconditional love. Wandering through the memories of her mind, she finds peace by recalling the progressive attitudes of her own grandmother and mother: “Both of them made me understand who I am and what my position is in this entire universe. On what basis can I judge people and the world as either right or wrong? Why do I forget that what seems wrong today might also be proved right tomorrow?”

Similarity of thought and self-examination unite these three women across time: unbeknownst to the other, each had quietly established educational and vocational institutions for the less fortunate. Their genuine nobility of spirit is not genetic inheritance, but a sustained link of wisdom demonstrated through practice, which impacts even those outside the ambit of their bloodline.

It is not her own children to whom Lavanyadevi bequeaths her remaining hopes of social reform. They are resentful of the attention garnered by their artless mother; it is the fifth generation instead who look up to her for advice. This Saptarshi Mandal of seven young men and women is the “manas-santaan” mind-soul-children to whom Lavanyadevi writes her last letters. Soldiers of the Lavanya Army, they dedicate themselves to micro-banking in Bangladesh, de-addiction centres in Tamil Nadu, funding from the World Bank for various welfare initiatives, and rehabilitation for sex-workers in Kolkata’s Sonagacchi — this last a space which author Kusum Khemani is also familiar with and has written about in her last book Lalbatti ki Amritkanyaayein (2019).

Something of the plurality which infuses Lavanyadevi could reasonably be attributed to her polyglot writer: Khemani reads, writes, and translates between Hindi, English, Bangla and is comfortable with Marwari as well. The Hindi of this book is threaded with phrases in Sanskrit, Pali, Haryanvi, Punjabi, Urdu and fragments of other poetic traditions merging into a fluid jheeni chadariya.

Mahanta has preserved these multilingual strands carefully through extensive notes, which illustrate the decade-long process of working on this particular edition. The introduction situates the larger canon of Marwari women writers in Kolkata, including Prabha Khaitan and Alka Saraogi; the conclusion addresses the phonics implications of inter-lingual dynamics as well as a general self-awareness about the limits of translation with a layered text like this one: “It is a hybrid Hindi text translated into hybrid English”. Descriptive paragraphs are especially able to retain the rhythm of the original through deliberate “Indianisms”; dialogue is occasionally stilted, but this is not altogether surprising given the ambitious generational sweep of the book. Mahanta’s own sensibility of inclusiveness, like Khemani’s, appears to align with some of the same glad traits which animate their eponymous heroine.

Lavanyadevi’s faith is a guiding feature, but it never mutates into dogma. To a Hindutvavaadi friend annoyed at her acceptance of other religions, she responds that her acceptance of all paths stems from Hinduism. Some people “do not for a moment hesitate to term their fanaticism as faith, eulogise it as dedication, and have no qualms about calling it bhakti, devotion. But bhakti is characterised by fluidity and giving… Like Lord Krishna, always be flexible enough to evaluate religion in the context of time and situation.” Her final missive to the three daughters urges them towards marriage, but the husband-candidates she suggests are of diverse religious and caste identities. And the last letter to the eldest son - by extension the other amritputra - could be seen as “emotional blackmail”, but is indeed her “sincere wish that each of you adopt at least one child with disability.” One may assume that this gentle spirit will likely have found its final goal — sublimation into mukti.

The writer is an independent editor and researcher currently based out of Dehradun