Legacy of an iconic ‘liberal’

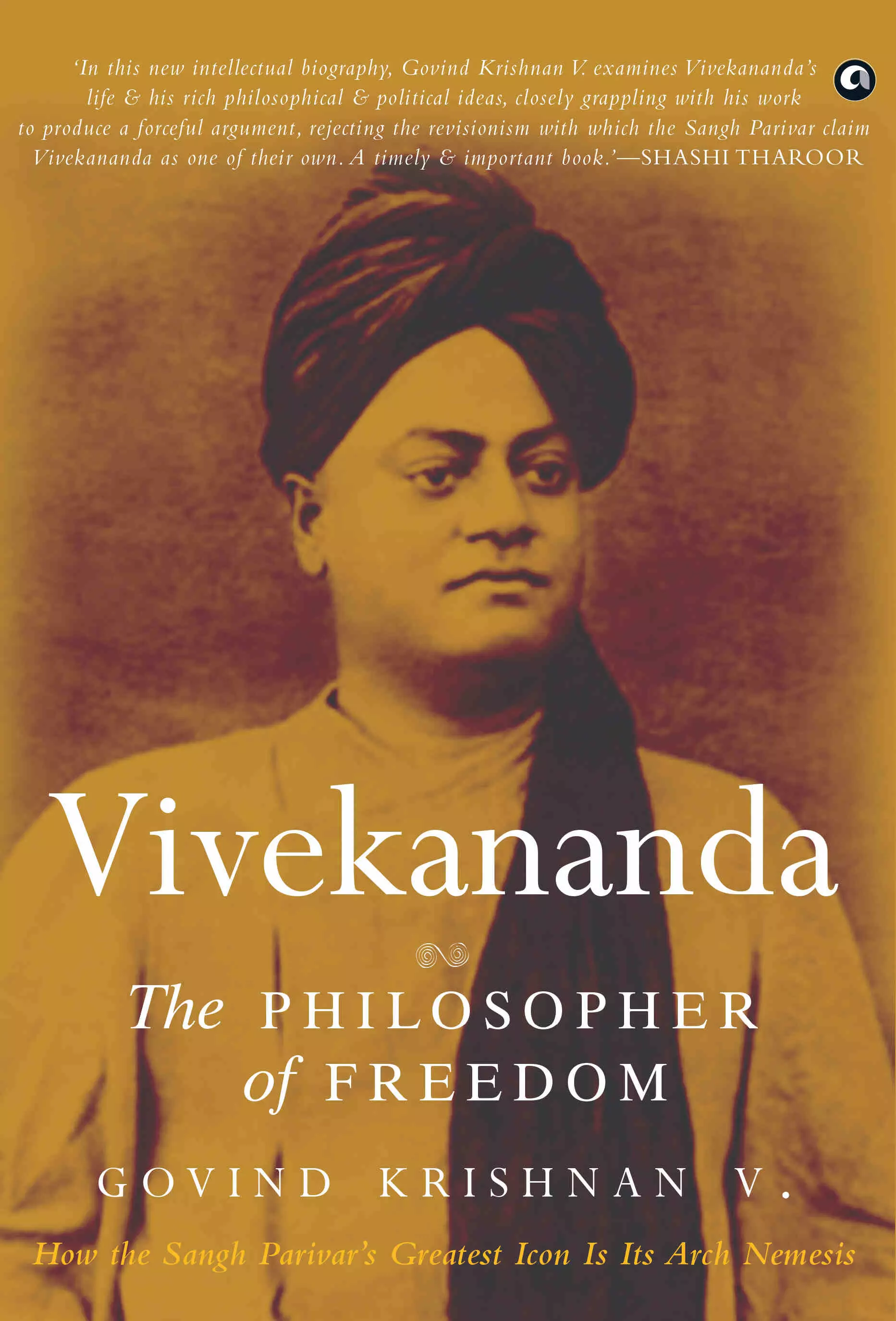

In the book ‘Vivekananda’, Govind Krishnan V presents a meticulous chronicle of the monk’s life, religious philosophy, social thought, and ideology, to cogently argue that the ‘liberal thinker’ was actually an arch nemesis of the RSS — which erroneously claims his legacy ‘Hindu’. Excerpts:

I am a monk,’ he said, as he sat in the parlors of La Salette Academy which is his home while in Memphis, ‘and not a priest. When at home I travel from place to place, teaching the people of the villages and towns through which I pass. I am dependent upon them for my sustenance, as I am not allowed to touch money.’…

There was a touch of pathos in the speaker’s voice and a murmur of sympathy ran around the group of listeners. Kananda (American reporters generally spelt his name as Vive Kananda in those days) knocked the ashes from his cigar and was silent for a space.

Presently someone asked: ‘If your religion is all that you claim it is, if it is the only true faith, how is it that your people are not more advanced in civilisation than we are? Why has it not elevated them among the nations of the world?’

‘Because that is not the sphere of any religion,’ replied the Hindu gravely. ‘My people are the most moral in the world, or quite as much as any other race…. No religion has ever advanced the thought or inspiration of a nation or people. In fact, no great achievement has ever been attained in the history of the world that religion has not retarded….

‘But, in pursuing the spiritual, you lost sight of the demands of the present,’ said someone. ‘Your doctrine does not help men to live.’

‘It helps them to die,’ was the answer….

‘The aim of the ideal religion should be to help one to live and to prepare one to die at the same time.’

‘Exactly,’ said the Hindu, quickly, ‘and it is that which we are seeking to attain. I believe that the Hindu faith has developed the spiritual in its devotees at the expense of the material, and I think that in the Western world the contrary is true. By uniting the materialism of the West with the spiritualism of the East I believe much can be accomplished. It may be that in the attempt the Hindu faith will lose much of its individuality.’

‘Would not the entire social system of India have to be revolutionised to do what you hope to do?’

‘Yes, probably, still the religion would remain unimpaired.’

This brief portrait of an informal conversation between Vivekananda and an American audience, published in the newspaper Appeal Avalanche, on 21 January 1894 contains many elements of the fundamental opposition between Vivekananda’s thinking on Hinduism and his way of life and what the Sangh Parivar espouses. Vivekananda did not consider Hinduism a static entity which had remained unchanged since the Vedic age. Vivekananda believed that Hinduism had certain fundamental spiritual truths discovered by its saints and prophets, but its religious and social forms have always kept on changing and will keep changing, even to the point that what was believed and practised in different historical epochs would be completely dissimilar and even contradictory. The Sangh Parivar on the other hand is obsessed with maintaining a Hindu ethos which they claim has existed with unbroken continuity since the Vedic ages. Vivekananda thought that Hinduism, (in the extended sense of a religious culture and affiliated social institutions) had much to learn from other countries; especially from Western materialism. And Hinduism also had unique spiritual wealth to give other nations, especially the West, where material power was concentrated. When Vivekananda contrasted the materialism of the West and the spirituality of the East, he was not creating a binary between the Abrahamic faiths and Hinduism. The binary was between Europe and America, and Asia. In defending Asia’s contribution to the religious thought of the world, Vivekananda told Western audiences that Jesus was from the Orient and pointed out that all the great religions of the world including Christianity, Judaism, and Islam had originated in Asia.

Vivekananda in the above quoted conversation talks about the possibility that Hinduism would in the process of cross-cultural contact with the West, lose much of its individuality, that is, its particular forms of religious and social expression, and concomitant forms of social life. Now these concrete peculiarities are what differentiate one religion from the other at the plane of lived reality. It is thus the basis of religio-ethnic identity. It is this identity which the Sangh Parivar mobilizes and which makes its politics of Hindutva possible by creating an ‘other’: the Muslim and Christian who do not share in this religio-ethnic identity. Vivekananda not only sees such an identity as dispensable, but sometimes, as in the preceding conversation, anticipated a future where what he here called ‘the individuality of Hinduism’, that is, its distinctive social and religio-cultural features, would become highly diluted as it became more and more permeable to ideas and modes of life from other cultures and civilizations. At the same time, he envisioned that Hindu spiritual ideas would also spread over the globe influencing and enriching other religions and creating a revolution in spiritual thought. The corollary of such a vision would

naturally be that in the future there would be no very distinct Hindu ethos to preserve, even if one were so minded. The long-term historical direction of development Vivekananda envisaged for Hinduism and Hindu society, (as well as all religions in the world), was a progression towards a universal spirituality, where individual differences of theology, mythology, ritual, and social practices would be considered secondary, non-essential matters. In other words, in Vivekananda’s vision, the conditions of possibility of religioethnic identity, the very basis of the Sangh Parivar’s Hindutva project, would be progressively negated.

There are two lines of thought at work here. One was Vivekananda’s conviction that the contact between the West and India, and the working of the forces of economic and cultural modernity would eventually affect a tremendous transformation which would change Indian society and world civilization. The second was

his belief that the same universal spiritual truths lay at the heart of every religion, and his hope that as human civilization advanced and people became increasingly more rational, this truth would be recognized. Vivekananda once planned to build a universal temple with a section devoted to the mode of worship of every religion in the world.

As Vivekananda said to an American audience ‘[I]f one religion is true, all the others must be true. Thus the Hindu religion is your property as well as mine.’ Vivekananda considered the advent of Sri Ramakrishna as setting in motion a new age of spirituality that would obliterate all caste and religious distinctions. Sri Ramakrishna in his spiritual quest had practised both Christianity and Islam. Sri Ramakrishna claimed that he had identical mystical experiences at the culmination of his practices of Islam, Christianity, and various forms of Hinduism. Vivekananda’s philosophy that all religions were true was based on Sri Ramakrishna’s putative spiritual experiences. Vivekananda said, ‘My master used to say that these names, as Hindu, Christian etc., stand as great bars to all brotherly feelings between man and man. We must try to break them down first. They have lost all their good powers and now stand as only baneful influences under whose black magic even the best of us behave like demons. Well, we will have to work hard and succeed.’

Vivekananda’s very mode of living was antithetical to the Sangh’s prescription for being a good Hindu. As per the RSS and the Sangh Parivar’s model, a good Hindu is someone who is a vegetarian, does yoga exercises (hatha yoga) with pride, doesn’t drink, and does not use addictive substances like tobacco. The cigar smoking monk hardly fits into this category, and the Sangh’s idea of the good Hindu wouldn’t fly with Vivekananda.

Vivekananda was a regular smoker. He started smoking the hookah as a college student (if not before) and found no reason to drop the habit when he undertook sanyas; this is mentioned in Vivekananda: A Biography and volume one of The Life of Swami Vivekananda.

(Excerpted with permission from Govind Krishnan V’s ‘Vivekananda’; published by Aleph Book Company)