Glimpses into the bigoted zeitgeist

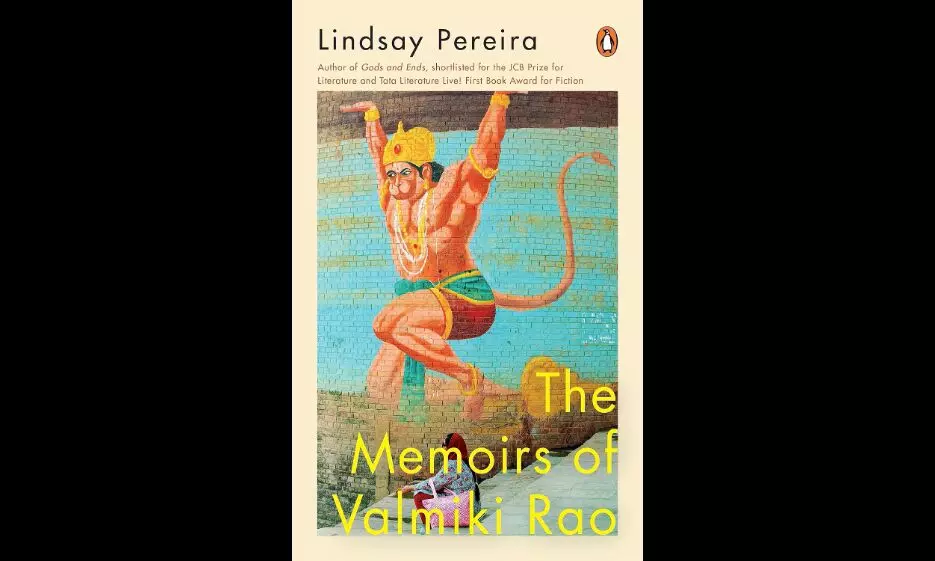

Set in the Mumbai of the 1990s, Lindsay Pereira’s The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao — contextualised around the demolition of Babri Masjid — is an unmissable retelling of Ramayana, portraying the bigotry that was simmering across societies and families during that period. Excerpts:

I want to mention that Ram Mandir again. I know it is exhausting to keep bringing it up, but how can I ignore it when my story revolves around that structure? In 1992, it was everywhere we looked. They had posters on our walls, on trees, even on lampposts outside the railway station. We couldn’t go anywhere without seeing that kesari colour and ‘Chalo Ayodhya!’. I still know nothing about Ayodhya. I haven’t even visited Kolhapur, though it is close to my ancestral village, so what can I say?

This mandir problem was around for a long time, but the British had managed to calm things down by putting up fences. We have no respect for fences, but we have always respected white skin, so they worked until independence. Then, when I was in school, just two years after Jawaharlal Nehru’s speech about India waking to light and freedom, we heard about idols that had been placed inside the mosque. Our government was new, so it locked the gates, forcing people to go to court. We all know how quickly the courts work.

For almost forty years nothing happened, until 1984 when a group called the Bajrang Dal appeared. They weren’t Marathi, but the bhaiyyas in our locality had some ties with them. They were young men with serious anger management problems and no jobs to distract them. You could tell they wanted nothing more than to tear everything down so, naturally, our own unemployed boys liked what they were saying.

We were older and had heard it all before, those lectures about how Hindus were failing Lord Rama. The Bajrang Dal changed their goal every other year. First, they wanted to protect India from communism, then they wanted to control Muslims, then they had a problem with Christian missionaries and, finally, they wanted us all to stop eating beef. I thought this would be the most difficult thing for our Marathi people to accept because villages in Maharashtra can’t afford to not cook beef, but I was wrong as usual. When you have no jobs for angry men, you can get them to support anything if you scream enough.

By the time Bajrang Dal flags appeared in Mumbai, they had found their big target. They wanted to wipe Islam off the face of India.

How could Ramu and Lakhya fall for this? Even if they didn’t believe in it, what made them spend time with men who did? Just because they dropped out of school didn’t mean they weren’t smart. Maybe it’s because they were struggling too. Vishnu had managed to find work for Ramu at his printing press, but he was just a helper doing odd jobs, bringing snacks, delivering finished products. Kavita made sure everything Vishnu earned went to Bantya’s school. She wanted tuitions for him and better marks and college. If Ramu and Lakhya resented their stepbrother, they kept it to themselves. It probably pushed them towards the shakha more often.

Ramu had also begun spending more time with Janaki. They went to see movies, and I once saw them at a restaurant near the station. Seth Lalji didn’t know anything about this. His daughter had never had a boyfriend, and he believed the only man she would ever have was the one she married. So, he carried on at the shop, while she took money from him to buy Ramu dinner. All of us knew, but no one said a word because we knew how angry the Seth would be, and we wanted them to be together. He thought he was better than us, and that his daughter was too good for us. If Ramu got Janaki, that would feel like a victory, so no one said a word, not even the ladies chatting outside the toilets. They didn’t say anything to Kavita because no one spoke to her. If her stepson married a rich man’s daughter, we hoped Janaki would finally put her in her place. This sounds petty, but small jealousies drive everything here. We carry grudges for generations.

Kavita was starting to realize she wouldn’t be able to order Ramu and Lakhya around much longer. That was another thing that joining the Shiv Sena gave our young men: power. They suddenly started to feel bigger than their salaries and jobs as office boys. They saw respect in the eyes of shopkeepers when they stopped to buy vada pav. They saw fear in the eyes of vendors at the bazaar. They were part of a larger group of people being trained to hate, and to look at people from outside Maharashtra as the enemy. When that wasn’t enough, even people from within became a problem unless they spoke the right language.

The smartest thing the Shiv Sena did was take an unfortunate inferiority complex and show jobless boys how to hide it. They taught them to hunt in packs. When the Bajrang Dal began looking for angry young men across India for support, the only ones they could think of in Maharashtra were sainiks. When that happened, Ramu and Lakhya’s story was finally put into motion. No one could stop it, least of all themselves.

None of this happened in perfect order. This is a story, so I must make it seem as if one thing followed the other. Maybe there was no connection between any of these things, but this is my story, and it is how I want to tell it.

***

Ramu and Lakhya’s home had long ceased to be a happy place. Vishnu was never around and, if he was, he was too drunk to change how his wife behaved. Kavita introduced a new hierarchy. Bantya came first, followed by Kavita, then Vishnu because she still needed his meagre salary. What was left, be it food or monthly purchases, was distributed between Kashi’s sons. Sometimes, all they had was half a plate of cold dal and rice, but they shared it without complaining.

I’m not trying to suggest they were saints who offered their troubles to God and prayed for their mother’s soul to come and rescue them. All I’m saying is we didn’t see them change outside their kholis. There was a calm assurance about who they were, which may explain why Ramu earned respect wherever he went, be it in school or the shakha. Anyone who walked away after meeting him felt as if they had spoken to someone with a solution. I have sensed that kind of power only a few times in my life, on rare occasions when my parents dragged me to some priest or holy man. Almost all of them were charlatans, but I remember one of them who placed his hands on my head and made me feel as if I had been bathed with warm water. I think that is how people felt when they spoke to this quiet, poorly educated, neglected boy from our chawl.

Some of the ladies of Ganga Niwas felt sorry for them because they were kind and helpful children who had grown into well-behaved young adults. The shakha must have offered them a sense of belonging they had lost after Kashi, but their behaviour towards us—their neighbours and acquaintances—never changed. They would help women carry their bags, invite Sundar to carrom championships in the chawl and tag along with the sainiks to some protest or the other if they felt it would lead to some good in the locality. I never saw them muscle their way to freebies or bribes, the way so many others did.

Ramu soon lost interest in the printing press and began looking for a new job. Someone at the shakha owned a restaurant that served fast food and needed a supervisor. He must have looked at the job as a step up after being an errand boy. He also wanted something better for Lakhya, who had been unemployed since he quit school, but an office job was impossible for anyone who wasn’t a graduate. More and more young people were beginning to apply for MBAs. No one wanted an MA or BCom anymore, they just wanted to do business.

(Excerpted with permission from Lindsay Preira’s The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao; published by Penguin Random House)