From Silence to Assertion

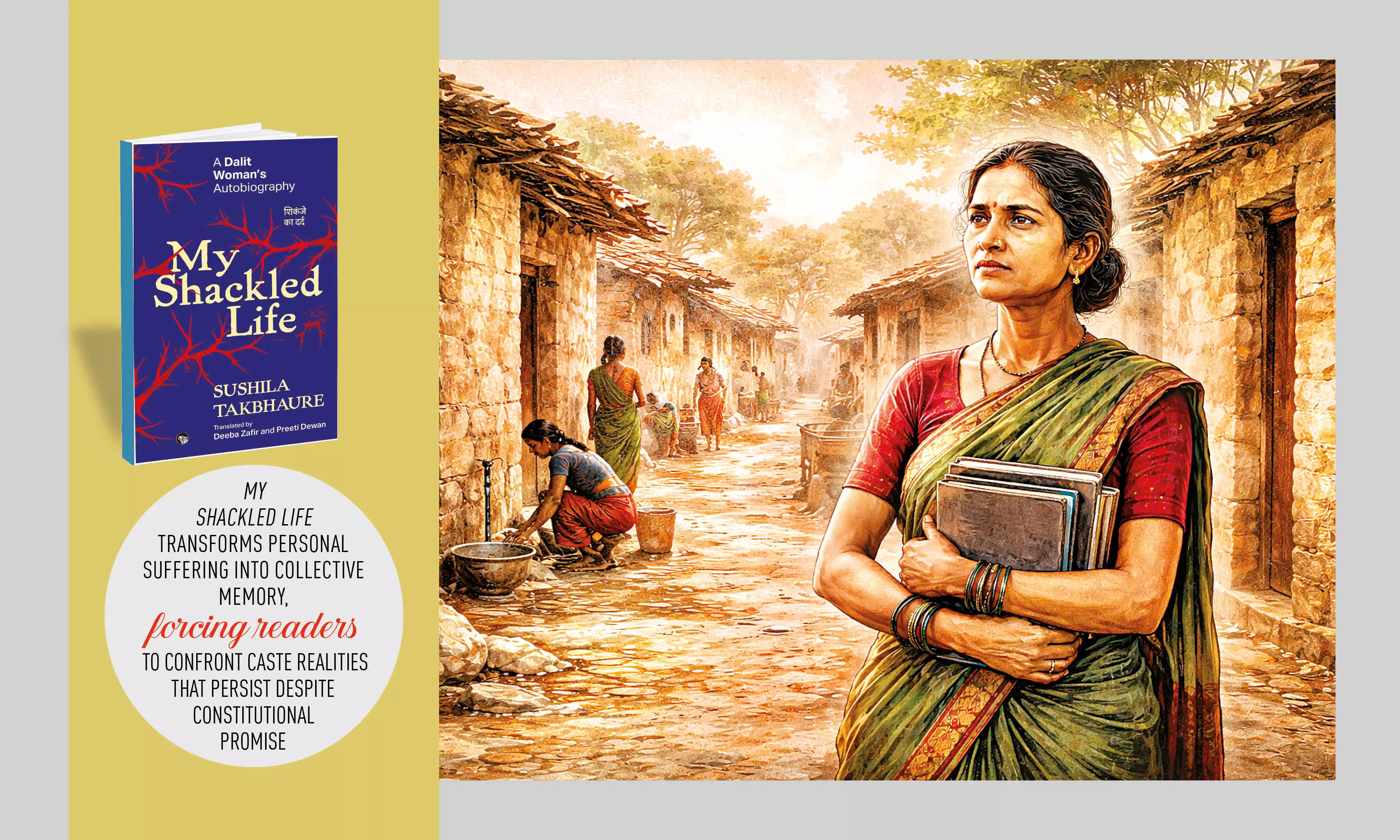

Sushila Takbhaure’s autobiography lays bare caste, gender, and poverty, tracing one woman’s struggle for dignity while exposing the enduring contradictions of India’s social order

I began writing this review on the 15th of February, the day of Shivaratri 2026, when the Aghoris invoke the Bhoots, Pischaasas, and the Doms of the cremation grounds to join the ‘all class–all caste–all gender’ celebration of Shiva’s marriage to Parvati. I had settled down comfortably with my coffee on a cosy armchair in my study to review My Shackled Life, the English translation of Sushila Takbhaure’s autobiography Shikanje ka Dard, when the Sunday edition of The Indian Express came in with a headline: ‘Everyday she cycles to Anganwadi, lays out mats and waits – for kids who never come’. This is the reportage of a four-month boycott of a Dalit cook in the Nuagaon village of the Kendrapada district of Odisha.

Nine decades ago, in 1935, Mulk Raj Anand wrote The Untouchable. Eighteen-year-old Bhakha was an ambitious young sweeper who excelled at playing hockey but was compelled by circumstances to clean the latrines in a cantonment town where the Tommies were his role models, although expectations ran high that the Mahatma’s call for the eradication of untouchability would make a real difference to the lives of people who lived on the margins. When I was given this book as a prize in school in 1975, it shook me to the core; I took solace in the fact that my immediate environment in the BSF campus at Jullundur Cantt (as Jalandhar was then called) was nowhere like the one described in the book. Three years later, I joined JNU and became painfully aware that caste was a category. Our politics remained ideological; the dominant debate was between the conventional Left (SFI) and the Liberals (Free Thinkers and Social Democrats). Back in the eighties, one could not have imagined the rise of either Phule-Ambedkar groups, or the AISA, or, for that matter, the ABVP and NSUI on the JNU campus. Dr Ambedkar was not part of the prescribed readings in the Modern Indian History course. Thanks to UPSC preparation, I read Annihilation of Caste and Waiting for a Visa, which showed how the pernicious hold of caste had entered Islam, Christianity, and Zoroastrian faiths as well.

Cut to 2026. This translation — the first proper Dalit woman’s biography from Hindi to English — has been fifteen years in the making, and Takbhaure had, at one stage, given up hope that it might see the light of day. While Anand’s Untouchable was written by a well-meaning upper-caste Gandhian reformist, My Shackled Life is the lived experience of ‘Siliya’ (the affectionate moniker given to Sushila by her Nani), who overcame multiple barriers: caste, class, gender, and space. I have added space — for her village, Banapara, on the Seoni Malwa railway line in Hoshangabad, reflecting the truth of Dr Ambedkar’s words about all villages in India as ‘a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness, and communalism’.

We begin with the story of her Nani, who was a certified midwife but also a sweeper, eking out a living by cleaning dry latrines. Their home in the Valmiki Mohalla was a veritable hell, especially in summers and the rainy season — damp firewood, an unlit hearth, hungry children, and despairing parents who often had to mortgage their brass pitcher to make both ends meet. Equally distressing, if not worse, was the treatment meted out in school where, as per a government order, all untouchables were bracketed under an omnibus category of Harijan. Teachers — who were mostly from the upper castes — would spare no occasion to rub this in, and even the village grocer would expect them to maintain proper distance for fear of being polluted. Ironically, this was the norm even when the Ram Lila composed by Valmiki was performed. From an early age, Sushila learnt ‘meek acceptance’ as a survival strategy, for there was hierarchy even within the shudras — the chamar was higher than the mehtar sweeper, and the dhobi and the nai were higher up the scale too. Her own academic excellence illuminated exceptional moments despite this discrimination: Purohit Guruji, her mathematics teacher, started addressing her as Sushila Saraswati instead of Sushila Harijan after she topped the eighth standard.

Change was in the air, and the safai karamcharis of Seoni organised a strike in 1968, followed by a protest against dry latrines, which made the community realise a sense of its own power. While the Mahatma had undertaken fasts for the liberation of the country, our protagonist had to go on a hunger strike against her own family only to get admission to a college. She eventually succeeded in her demand and became the first ‘graduate’ of her community. Married to a much older but ‘educated school teacher’ who was willing to allow her to work after marriage, she began life again in a one-room tenement which she and her husband had to share with six others. Subject to domestic violence and verbal assault for the first two decades of her marriage, she still credits her husband for her professional growth but cannot refrain from asking: ‘Why was he so egoistic and condescending? Why did he belittle me so much?’

Even as the Takbhaure couple overcame their economic hurdles — both were educated and held regular jobs — visible and invisible discrimination was a regular feature of their lives, from renting or buying houses to car pools and even literary conferences. Sushila ji knew that education was the key to empowerment, but every step of her journey, from getting admission to the Master’s programme in Hindi to enrolment and successful defence of her PhD thesis, was paved with difficulty. As a mother of four with an overbearing husband and mother-in-law, there were times when she felt absolutely forlorn and frustrated. Yet giving up was never an option. It was her writing — both poetry and prose — that gave her the reason and the hope to live. And, even though many of her friends and colleagues asked her to write Lalit rather than Dalit literature, she said, ‘I don’t seek a name for myself. I only want to work for my community and ensure that my people are treated with respect’.

And through her many stories and poems, which are now part of the syllabi in several universities; her speeches at Ambedkarite and BAMCEF conferences; and her keynotes at Dalit and women writers’ conferences in India and abroad, Sushila ji has brought to the fore the aspect of Dalit Chetna to members of her community and to the functionally literate, conformist Savarnas who hold the brooms every Gandhi Jayanti for photo-ops and election campaigns. As she points out, campaigns for the eradication of untouchability while holding varnashrama dharma as a core value is the bitterest contradiction of our ‘liberal society’.

But I want to close with a silver lining. On the 18th of February, The Indian Express reported the impact of their story: thanks to the intervention of the district administration, 15 of the 20 enrolments came to the Anganwadi centre. We do not know how many more disruptions of this nature are required before Ambedkar’s Constitution will hold real meaning for one and all in the Republic of India, that is Bharat.