Falling to His Own Choices

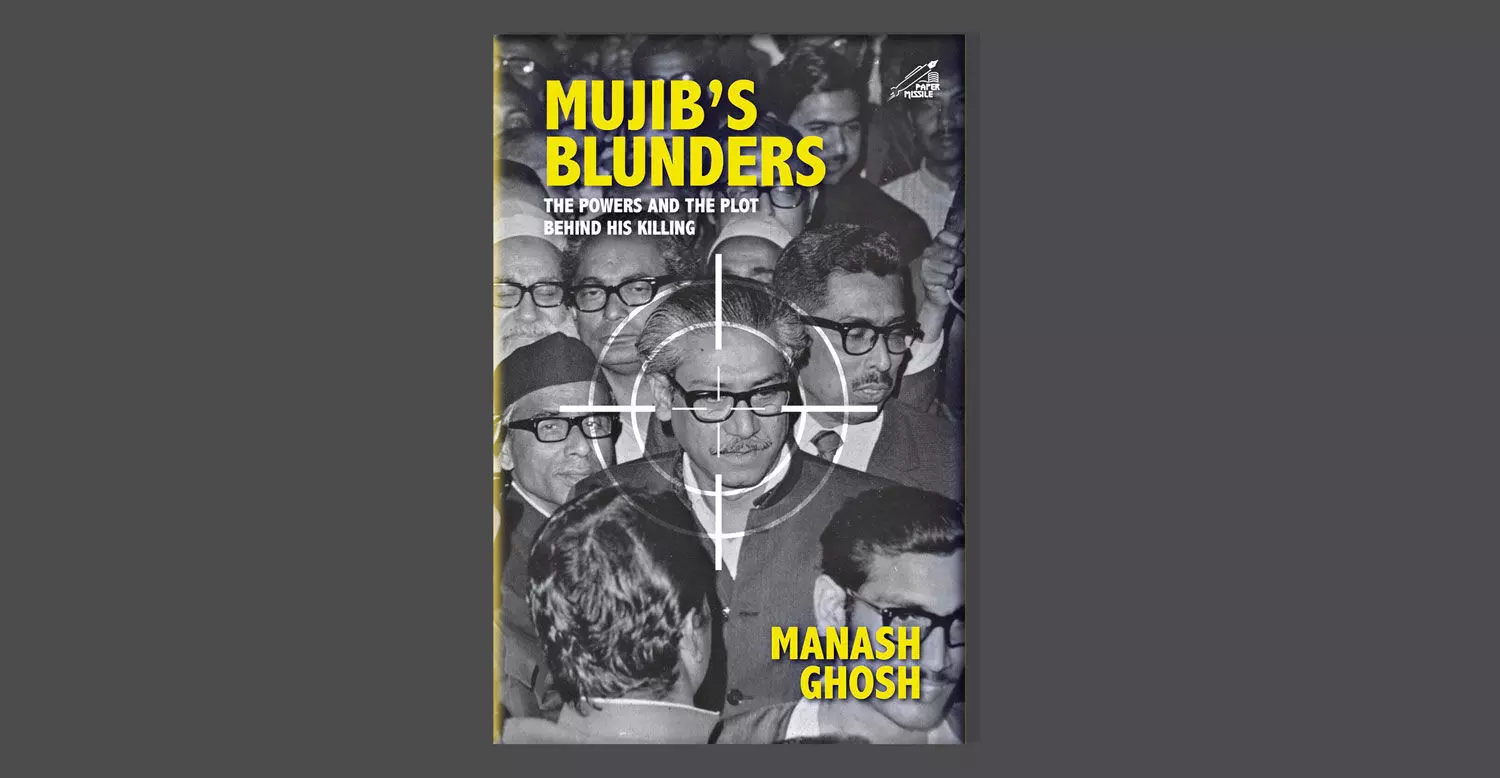

In Mujib’s Blunders, written by Manash Ghosh, the fatal missteps of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman are laid bare. Be it his misplaced trust, sidelining of loyalists, flirtation with Islamists, or pursuit of Pakistani recognition—everything paved the path for betrayal, conspiracies, and his tragic assassination. Excerpts:

During Mujib’s visit to Calcutta on 6 and 7 February in 1972, he had invited Mrs Gandhi to visit Dacca at her earliest convenience. In his speech at the Dacca farewell parade held by departing soldiers of the Indian Army he had said, ‘Bengalis of all class and sections were waiting eagerly to welcome her and accord her a grand reception as she was no longer just a leader of India but of all persecuted people in the world.’

Mrs Gandhi arrived in Dacca within five days of the Indian troops’ withdrawal, which coincided with Mujib’s birthday. On her arrival she conveyed on her personal behalf and also on behalf of 55 million Indians their good wishes on his 52nd birthday. The two-day official visit—17 to 19 March—unveiled new vistas of co-operation and friendship between the two countries.

Addressing a mammoth public reception accorded to her in the historic Race Course Maidan, Mrs Gandhi said, ‘Come what may, Indo-Bangladesh friendship will always remain intact. Nobody can drive a wedge between us.’ This was in response to Mujib’s apprehension that ‘countries and forces inimical to both India and Bangladesh would do everything possible to disrupt our ties and create bad blood in our relations and friendship.’ Then turning towards Mrs Gandhi, Mujib went on to say,

What you did for Bangladesh was beyond your call of duty as a national leader. You did that because you felt you had a great humanitarian responsibility to fulfil and also to uphold certain cherished values dear to you and us. You are so different from other leaders. That’s why what you and Indian people did for Bangladesh, disregarding all kinds of odds and hostility, has few parallels in world history. It is because of this reason that Mrs Gandhi and India find a special place in the hearts and minds of our people.

What touched hearts in Dacca’s biggest ever crowd turnout was Mrs Gandhi’s repeated assertion that she was confident that Bangladesh, under Sheikh Mujib’s bold and charismatic leadership, would be able to successfully rebuild itself into a prosperous nation on the ruins of death, destruction and misery of its people. But her most profound tribute was when she remarked she had witnessed many Liberation Wars during her lifetime, but never before had she come across almost an entire population who, so inspired by the ideals of their great leader, had so extensively participated in the Liberation War.

As a journalist what surprised me the most was the sizable presence of ladies and youths at the meeting. Majority of the ladies were ordinary housewives, but there were also many who came from affluent families and had never attended public meetings of any kind in the past. They had come because they wanted to see and hear the great Indian leader’s speech live and this made them sit and rough it out on the floor of the Maidan for over three hours.

Mrs Gandhi’s meeting with Bangladeshi intellectuals was somewhat rough as she was grilled by a section of them about India’s ‘questionable role’ during the Liberation War. Just as during the Liberation War, the anti-Tajuddin faction of the Awami League leadership—led by Khondokar Mushtaq—was critical of her government for not according diplomatic recognition to Bangladesh’s provisional government, some of the intellectuals present wanted Mrs Gandhi to explain the reasons for ‘not recognising the government-in-exile in time’ which, according to them, could have hastened the process of their country’s liberation and minimised their people’s bloodbath.

Mrs Gandhi explained that whatever India did for Bangladesh was from the point of view of good neighbourly considerations and nothing more. Moreover, the reason for not recognising the Mujibnagar government soon after its formation was because if that was done, then that step would have eventually proved counterproductive as it would have seriously threatened Bangabandhu’s life. Her government had information that the Pakistani military rulers in a revengeful act would do something highly irresponsible which would have certainly changed the course of the Liberation War. ‘We wanted Bangabandhu’s early release from Pakistani prison…unharmed. Our intentions were good and there is no reason why they should become suspect in the eyes of the people of your country now,’ Mrs Gandhi had said with some feeling of annoyance.

The most tangible outcome of Mrs Gandhi’s Dacca visit was the signing of the Indo-Bangladesh Treaty of Peace, Friendship, and Cooperation which was almost fashioned on the lines of the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace and Friendship signed in August 1971. The treaty was mooted by India considering the ‘fluid internal security situation prevailing in Bangladesh.’ Soon after liberation, Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmed was first sounded out by D.P. Dhar, chairman of the Policy Planning Committee of the External Affairs ministry, on the idea of entering into such a treaty with India.

Mr Ahmed was non-committal on the issue as he knew any decision, however well intentioned, would raise a massive furore within the cabinet led by Mushtaq and also others in the Awami League. Moreover, it was not an opportune time for signing such a treaty with India then because of the presence of Indian troops in Bangladesh. So he relegated Dhar’s proposal to the backburner for the time being and left it for Bangabandhu to take the call when he returned home.

After the withdrawal of Indian troops on 12 March, Indian officials felt encouraged to broach the proposal to Bangabandhu who seemed amenable to the idea with minor changes. This was told to me by Mr J.N. Dixit, India’s deputy high commissioner in Dacca who was involved in various stages of the treaty’s drafting exercise.

The first person to tell me that the treaty had come into effect at a ‘wrong time’ was Zahur Hossain Chowdhury (former editor of Bangladeshi daily Sangbad) who said that India, before drafting the treaty, should have taken into account the existing ground reality of the growing anti-India sentiment that was being deliberately fanned by pro-Pak and pro-China elements in the Bangladesh polity besides a large section of the Bangladesh media. He was also critical of Mujib because without neutralising those fringe groups politically and by other means, he had gone ahead with the treaty.

(Excerpted with permission from Manash Ghosh’s Mujib’s Blunders; published by Niyogi Books)