Enigmatic universe of a maverick

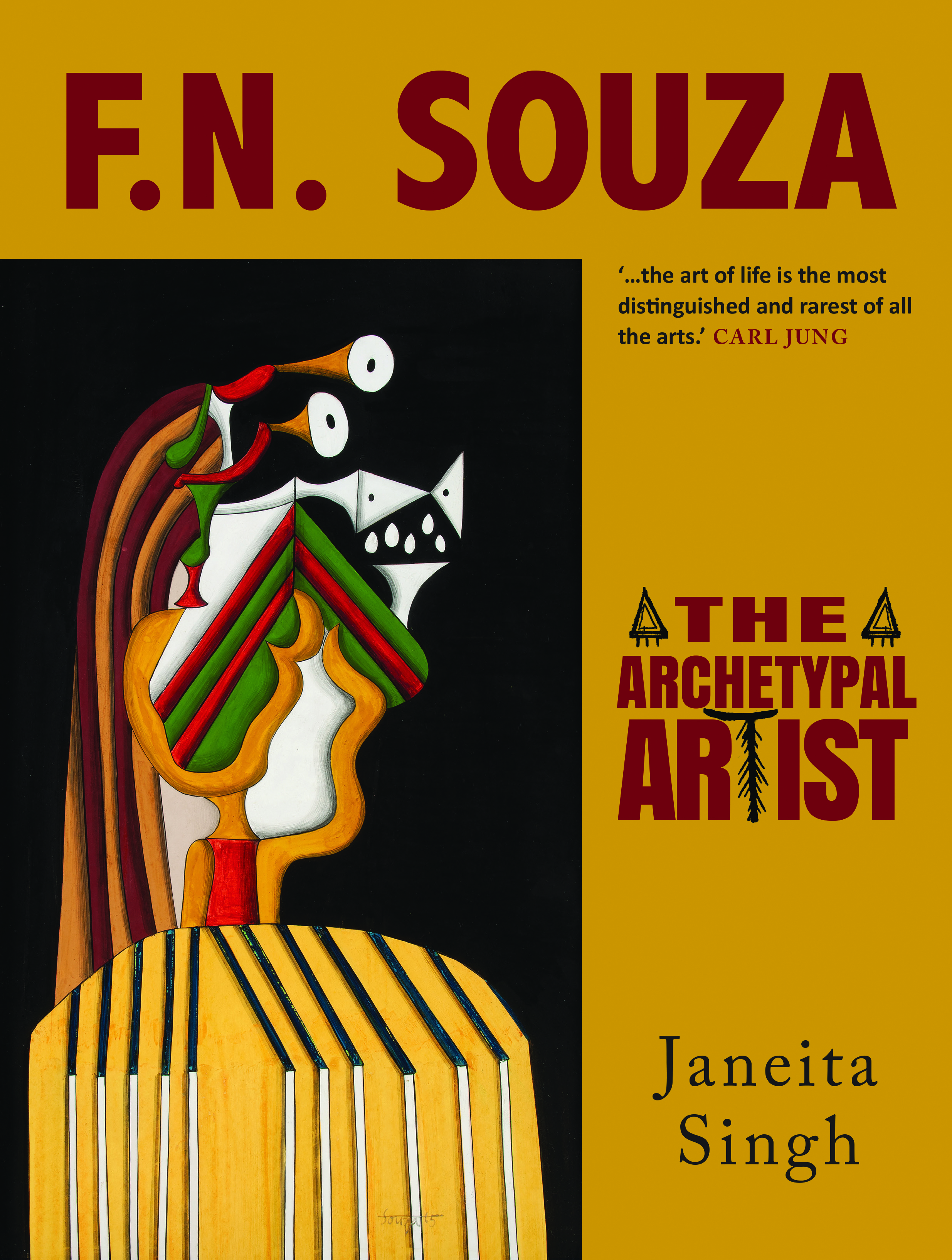

Diving into the vivid realm of FN Souza’s life and art, ‘The Archetypal Artist’ by Janeita Singh takes readers on an enthralling journey through 21 essays that seamlessly blend diverse disciplines—from art history to Jungian analysis, unravelling the depths of cultural constructs of life, body and sexuality. Excerpts:

Souza’s life and art are a study in human psyche, because of their potential to glean truth through a deep connection with the unconscious. Souza drew heavily on Eastern/Western psychology and ancient classical texts for his art. He became an archaeologist of the soul and his intuitive art’s unceasing revelations continue to illumine the human psyche, long after he ceases to be. Some works that offer such scope are Death of a Pope, 1962; Eros Killing Thanatos, 1984/85; and Nude with Mirror, 1949.

In his teens, Souza seems to have set out on a quest for wholeness, through the engagement of his ego with his unconscious. In sync with Jungian philosophy, Souza’s pneumatic core (Self) appears to have become uncannily vociferous and vital at a very early stage and demanded its participation through art. The unconventional imagery that his unconscious led him to was deciphered and coded onto his canvas. Aided by this engagement in his psyche, Souza was well on the route to becoming the seminal modernist of his times.

To become the archaeologist of the soul at such an early stage is no mean feat; a lot had already gone into the process by the time Souza was in his 20s. He had faced many misfortunes in childhood. His growing up years had been marked by illness, death and an acute observation of hypocritical social institutions. He was a lonely child given to rebellion and anger. He experienced his mother’s widowhood followed by beatings by his stepfather. On the one hand, his mother wanted him to become a priest, a religious calling that he felt abounded in conundrums. On the other hand, the educational system did not accommodate the charged energy of a young boy whose head raged with questions. His alienated ego seems to have become a precursor on his journey of individuation; and for Souza it all happened in a span of the first 10 to 15 years. Jungian psychology, ancient Gnosticism and Sankhya philosophy are but pointers to experiences of psychic transformation. It appears that through psychic connection to the collective unconscious in his teens, he arrived at exceptional images in his sketch book while still in college. His art began filling the lacunae in the myths he experienced in day-to-day life.

To me the unconscious was a matrix, a sort of basis of consciousness of a creative nature, capable of autonomous acts and creative intrusions into the consciousness. Philemon and other figures of my fantasy represented superior insight; there are things in the psyche which I do not produce, but which produce themselves and have their own life. All my work, my creative activities, has come from those initial fantasies and dreams that began in 1912.

Besides its nihilistic and destructive nature, Jung considered the unconscious to be a storehouse of power and potentialities, which, if tapped, could lead to human wholeness, in contrast to Freud who saw it as a repository of psychotic afflictions. Souza seems to have organically gone along with the former in his development as a great artist.

Souza belonged to two great cultures, the Christian and the Hindu way of life. He had grown up with living myths of both cultures, but in itself neither fulfilled him. Just like Jung who found the ‘Alchemical myth’ a richer and more complete continuation of the Christian myth, Souza gives the impression of having sought an amalgamation of myths, drawing upon resources of collective unconscious to complete what had gone missing in the individual myths.

The Christian myth is deficient in not including enough of the feminine. In Catholicism, we have the Virgin Mary, but it’s only the purified feminine, compromised by virginity and maternal instinct; not the dark feminine and in excluding that and treating matter as dead and the realm of the devil and in not facing the problem of opposites, of the problem of the physical and evil, humanity faces a spiritual barrenness, and the myth is deficient and gives no answers.

I believe, an assured parlance and confidence marked Souza’s maiden artworks, as he painted feminine/masculine archetypes with ardour. He went on to depict the evil, underbelly of modern life—its violence and corruption in the citadels of power and authority that held the human soul ransom every step of the way. Repressed figures like the feminine appeared in glorious grotesque forms on his canvas, whereas pompous authoritarians were reduced to emaciated caricatures.

A second phase of Souza’s psychical churning came about from the 1960s. At that time the atomic bomb and space explorations loomed at the height of the Cold War. The heightened border tensions and electoral jingoism made it imperative that the human collective no longer ignore man’s psyche. More than nuclear war itself, it was the human psyche that had become the dreaded threat to human existence.

Souza’s artwork seems to have taken on messianic tones, towards a path of peace and fellowship, also compiled in his book, The White Flag Revolution. His artwork right up to the 1990s is determining and thrusts hard towards the goal of renewed patterns of thought. Noteworthy paintings such as Eleventh Chapter of Bhagvad Gita, Prakriti Yoni: the holder of mankind, Redmonian Venus, East-West Encounter series, varied impressions of Lajja Gauri, those innumerable ‘Heads’ and Transfiguration, clearly show his deep passion for alternative ways of being, heralding evolved mind-sets with a renewal of the collective consciousness.

In the 50s and 60s there arose a great fear that the world was on the brink of nuclear war. It would be the ultimate war; to say goodbye earth…the acme of all human knowledge has resulted in the making of the bomb…It’s all wrong and will end in ashes. That is why my painting is in grey.

Carl Jung said, ‘Not nature but the “genius of mankind” has knotted the hangman’s noose with which it can execute itself at any moment.’

Prominent psychological studies by Souza include: Death of a Pope, Eros Killing Thanatos and Nude with Mirror, to name a few. In each of these artworks Souza’s layers multiple complexities. He builds bridges between knowledge systems of East and West, ancient and the modern, existential and mythological, in an endeavour to render lucid narratives. A psycho-spiritual meditation on these paintings shines light on the shadows in the collective human consciousness.

Death of a Pope, 1962, is an illumination of the Papal power and corruption hidden behind the power invested in him (the Pope). A comparative study with renditions by Titian, Velazquez and Francis Bacon unearth the importance of its treatment by F.N. Souza. In the renditions by Titian and Velazquez, the Pope is depicted resplendent in satin robes, seated on a high decked upholstered chair. The painters have captured the cunning glint in the eye and skull-like bloody hands, also drawing attention to the power play at work by painting the figures of their grandsons in the portraits. Bacon is superb in his visual language of a screaming Pope, held back by yellow cords and tied to a seat of power. Souza takes the psychological story forward by rendering an emaciated Pope, laid up supine in bed, covered by a dirty white bedspread, completely stripped of his refinements. All that is left of this towering personality on his death bed are slitted eyes, a prominent curved nose, shark-like pointed teeth and hands ending in claw-like nails. Equally ugly men surround his deathbed, mumbling the last prayer, whilst visualizing their own ascent to power.

Not long after Souza arrived in New York, he travelled across many states in the US and simultaneously began a close reading of Indian classical texts like the Bhagavad Gita, the Vedas and Upanishads. The painting B.G. Ch Eleventh Chapter of Bhagvad Gita is a study in the primeval cosmic form of the Lord, enumerated from the 11th Chapter of the Bhagavad Gita.

(Excerpted with permission from Janeita Singh’s ‘The Archetypal Artist’; published by Niyogi Books)