Elegance on the floor

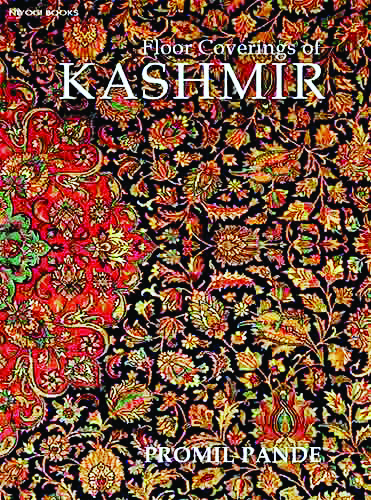

Meticulously researched and richly illustrated, Promil Pande’s Floor Coverings from Kashmir is an enduring account of the region’s opulent material culture, and dissects the existence of age-old craft traditions by putting them in wider ethnic-cultural contexts. Excerpts:

Floor coverings of Kashmir are categorized as handicrafts by the Ministry of Textiles in India. This is the organization responsible for policymaking, development, growth and progress of the textile sectors including the handloom and handicraft divisions. As a significant exportable, floor coverings of Kashmir play a vital role in the economy, representing a large and dynamic segment of the manufacturing sector (Gopal, 2016: 1). Craftsmen and women carry out manufacturing in household workshops located in proximity to each other, resulting in craft communities becoming engaged in ‘craft-based manufacturing’ (Seth, 2018: 31). The location of production, understanding and handling of material, knowledge and mastery of techniques, processes of making and the customs of the division of labour based on expertise are cultural attributes of the long-standing manufacturing traditions of Kashmiri floor coverings. The craft practices in Kashmiri floor covering production, therefore, are regionally specific, governing the aesthetic quality, which has always, to some degree, been dependent on technical processes of manufacturing, enabling appreciation and further furnishing indispensable clues to identification (Pope, 1965: 2437). The craft communities, traditional practices of production and material culture are thus interlinked and constitute the indigenous craft traditions influenced by regional cultures practised for generations by the artisanal communities. Craft and culture, however, are conceptualized in various ways by academic disciplines. An understanding of some of these perspectives enables identification of the tangible and intangible constituents that form the underpinnings for contextualizing Kashmiri craft practice as culturally and regionally specific.

Academic Perspectives on Craft

As one of 10,000 most commonly used words in the Collins dictionary today, the term ‘craft’ was earlier used in contexts not related to creative activities of any kind. Over the years, however, it has come to be used to describe art, design, technophobia or anthropological significance. It also represents apparent traditions, functional artefacts, an old or newage lifestyle or ethnic iconography and mannerisms of individual races. More recently, it is being considered and described as a consortium of genres, as a way of working in the visual arts, implying an established way of making particular products, using a set of technologies, processes and materials, such as glassmaking, metal-smithing, painting, sculpture and tapestry, suggesting that a fully developed genre provides the principal method of creating things of artistic quality (Greenhalgh, 2002: 1, 12, 18).

Craft production of one kind or another is a tradition enjoyed by all nations; however, over the years, modernist developments have changed the way craft is understood and viewed. Until the 20th century, ‘craft’, ‘art’ and ‘design’ were not clearly defined as separate distinguishable terms. The separation of craft from art and design is a phenomenon of the late-20th-century Western culture, whereby implying ‘making objects’ was different from ‘having ideas’ and ‘creativity’ was a mental attribute preceding and divorced from the knowledge of making (Dormer, 1997: 18). The grouping and classification of various genres as art, craft and design was thus a system understood by and benefitting the marketplace, galleries and governments, which adhered to a tacitly agreed financial pecking order driven by an established framework (Greenhalgh, 2002: 4). As a result of this classification, craft experienced intellectual isolation since the 1920s. On the one hand, it was being deprived the prestige of high art, while on the other, its inadequacy of reproducibility rendered it unsuitable as product design. Thus craft ‘straddled between an art and design economy’, occupying an economic space whereby objects, though individually handmade, were sold at mass production prices (Greenhalgh, 2002: 6).

In today’s developed nations, where few, if any, traditional craft producers survive (Liebl and Roy, 2003: 5366), the interpretation of ‘craft’ is wideranging, continuously developing and changing over the past three centuries without ‘a solitary or consistent meaning and holding on to the earlier varied shades of meaning.’ Dictionaries define craft as ‘an occupation or trade requiring manual dexterity or artistic skill’ (Merriam Webster); and ‘skill and expertise, especially in relation to making objects’ (Cambridge). Adamson views craft ‘as a process or a way of doing things organized around the material experience which depends on skillful hands manipulating the resistances of material’ (Adamson, 2016: 4). Sennett’s (2008: 9) description of craft, however, is more explicit: it not only focuses on the motivation and objective standards but further argues that all skills, even the most abstract, begin as bodily practices and the technical understanding develops through the powers of imagination (Sennett, 2008: 10). Michelangelo had famously suggested the connection between hand and mind, when he stated ‘… the hand serves the brain…’ (Brown and Vasari, 1907: 179–180). Building on this idea, Coomaraswamy (1932: 192) posits ‘that creative activity is completed before any physical act is undertaken.’ Sennett (2008: 10) and Coomaraswamy (1932: 215), therefore, suggest ‘craftsmanship is an enduring, basic human impulse, the desire to do a job well for its own sake’ and ‘every man an expert in his vocation’—implying that craft can apply not only to artisanal work but also serves the computer programmer, doctor and parent as well.

(Excerpted with permission from Promil Pande’s Floor Coverings from Kashmir; published by Niyogi Books)