Dreams and the Dawn of FTII

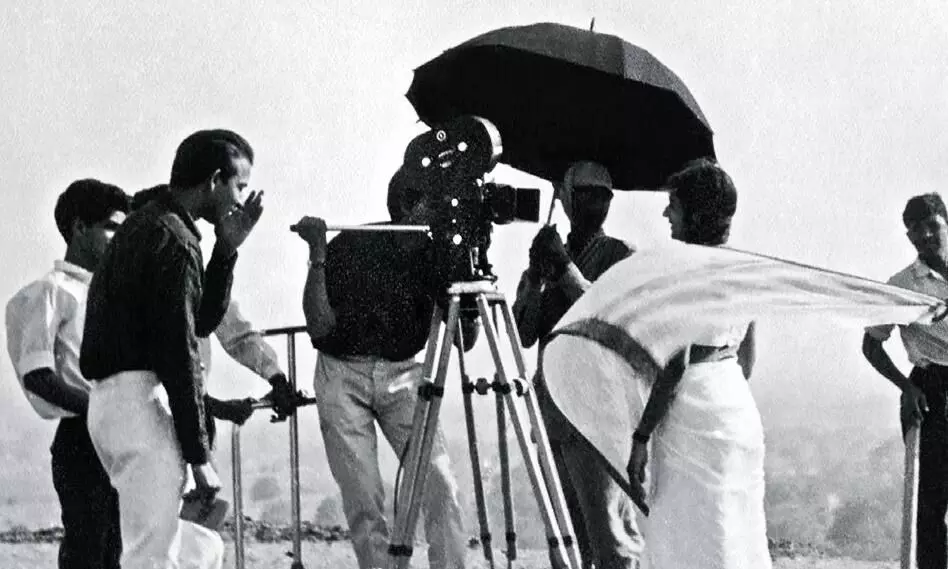

In The Maker of Filmmakers, Radha Chadha traces how the legacy of Prabhat Studio shaped the Film Institute of India and the professionalisation of Indian cinema; Excerpts:

The newly opened Film Institute of India lay a few kilometres away from the city centre of Poona, on a scenic 21-acre plot of land that had once housed the Prabhat Film Company. A wide tree-lined road cut through the middle of the campus, pulling you in at the entrance, and rising gently as it extended all the way to the base of a hillside at the far end. On the right side of this road were four of the five erstwhile studios of Prabhat, the most imposing being Studio No. 1—one of the biggest in Asia—its massive exterior wall covered with lush green creepers, its cavernous insides containing a labyrinthine structure of suspended catwalks, dangling wires and outsized lights. Studio No. 1 was at the heart of the Institute, flanked by buildings with classrooms, teachers’ offices and technical facilities. Leading up to it was the mango tree that would acquire mythical status as the ‘Wisdom Tree’. Across from the tree was the canteen, and up ahead, in a small cottage, the Principal’s office. Beyond the studio buildings lay a village pond, a forest preserve, and vast open spaces for outdoor shoots. The air was cool and crisp on the August day when the first batch of students arrived on campus. Sunlight streamed through the leaves. Birds twittered. It was the kind of idyllic setting you might find in a film. Or as David Lean, who visited in the early years, put it: ‘What a lovely place to learn our wonderful profession’.

The filmmaker V. Shantaram, who had briefly been Jagat’s boss at Films Division, was one of the pioneering spirits behind Prabhat, which he had founded in 1929, along with his partners V. Damle, S. Fattelal, K. Dhaibar and S. Kulkarni. Some of them still lived in bungalows neighbouring the Institute, and we got to know them and their families—Fattelal’s grandson would come over to our home to play with my brothers. The cameras, sound recorders and editing tables that the students would soon be using for their exercise films were the very same that had shaped Prabhat’s films like Sant Tukaram (1936), the first Indian film to win an award at the Venice Film Festival, and Duniya Na Mane (1937), a gutsy commentary on the social injustice of marrying off young girls to older widowers. The Prabhat legacy lived on in some of its former staff too, among them technicians, carpenters, drivers, security staff, even the dhobi, a number of whom now worked for the Institute and loved to tell stories of the studio’s golden era.

Prabhat’s golden era had indeed been highly innovative, creatively courageous and resoundingly successful at the box office. When the government bought Prabhat in 1959, perhaps the strongest asset it got, unasked for and unappreciated as it might have been, was this plucky cinematic spirit. The Film Institute would build on it, translating it for cinema’s next era.

Does the culture of an organization live on in its setting? Hard to say, but one key element of Prabhat’s culture, the clockwork precision with which it ran its ambitious film production programme—not necessarily the norm elsewhere in the film industry—would also characterize the Film Institute, almost from the beginning of its existence. The celebrated Marathi writer P.L. Deshpande described Prabhat’s culture this way:

Strict management was the salient feature of Prabhat. The main gate was vigilantly guarded. The employees were required to punch the cards. Punctuality was the rule without exception. Nobody would be spared for tardiness. Lunch hour was actually ‘half-an-hour’. Lunch time was proclaimed by a siren. Shantaram-bapu would finish his lunch within fifteen minutes and resume work. Hangers-on, snobs and show-offs, lackeys and yes-men pampering egos, they had no place in the premises.

There were strict rules about behaviour too, and one of them forbade romantic entanglements with the actresses in the studio. Alas, two of the founding partners, K. Dhaibar and V. Shantaram, found themselves head over heels in love and shortly thereafter out of Prabhat. Shantaram had become involved with the actress Jayashree,6 who had just debuted in Padosi, and he left in 1942, which proved to be a turning point not only for Shantaram but also for Prabhat. While Shantaram reinvented himself with aplomb in Bombay, setting up his own production company and unleashing a series of hits, Prabhat declined and crumbled in the following years. By 1951, it was knee-deep in internal squabbles, legal battles and financial pressure.

India’s broader film industry was in trouble too, and that same year the government-appointed Film Enquiry Committee, headed by S.K. Patil, released its landmark report, making extensive recommendations to fix the film industry’s knotty problems. The roots of the problems went back to the World War II period, and the exorbitant profiteering that accompanied it, which had created a new tribe of independent producers, eager to gamble their ill-gotten gains on the movie business. Whereas the studio system had everyone on a salary, including popular actors, directors and songwriters, these new producers dangled large sums of money to induce them to work freelance. The sums were heady. Successful stars could make a year’s salary in one film, and they started signing films indiscriminately, often committing to more hours than there were in a day. The freelance model took root, characterized by over stretched stars, hopelessly delayed schedules, and plenty of black money which was concealed from the tax authorities. This new power equation, in which a small number of big stars held sway over the entire industry, came to be known as the ‘star system’. Chaos ruled. The overall quality of films deteriorated. Filmmaking, always a risky business, became even more so. Most producers lost money. The industry went into a tailspin. The Film Enquiry Committee noted: ‘Film production, a combination of art, industry, and showmanship, became in substantial measure the recourse of deluded aspirants to easy riches.

One of the Film Enquiry Committee’s recommendations concerned the setting up of a film institute for the purpose of training a cadre of technicians who would bring a measure of desperately needed professionalism to this increasingly wayward industry. The studios themselves had once played the ‘film schooling’ role, enabling newcomers to learn the craft by watching and doing, thereby providing an informal apprenticeship. For example, Shantaram had learned his craft at the studios of Maharashtra Film Company in Kolhapur during the silent film era of the 1920s. He had done it all—from cleaner to camera assistant, from errand boy to actor, from scene painter to laboratory assistant.9 But with the studio system in decline, and this profligate new breed of independent producers holding sway over the film industry, there was no longer an appetite, or an opportunity, for that kind of in-depth training.

Excerpted with permission from The Maker of Filmmakers; published by Penguin Random House